Directors – Michael Powell, Emeric Pressburger – 1949 – UK – Cert. PG – 106m

*****

In London during World War Two, a back room boffin and bomb disposal man struggles with alcoholism – 4K restoration played at BFI Southbank on Tuesday, May 28th prior to release on Blu-ray, DVD and Digital on Monday, June 3rd

This black and white, post-war era drama isn’t the first film that comes to mind when people think about Powell and Pressburger – it was made immediately after what today are regarded as three of their best colour features – A Matter of Life and Death (1946), Black Narcissus (1947) and their arguable masterpiece The Red Shoes (1948). And that was preceded by one of their finest black and white works, “i know where i’m going!” (1945).

In many ways, The Small Back Room couldn’t be more different. There’s a marvellous sense of whimsy about those films, even if the later ones are intense and savage in places. Like Black Narcissus and The Red Shoes – and, for that matter, Powell’s late solo masterpiece Peeping Tom (1960), an intensity lies at the heart of The Small Back Room.

Gone are the light, airy spaces of the earlier films, their sense of the outdoors expanse (and, in The Red Shoes, the expanded landscapes of the eponymous ballet sequence within the film). The Small Back Room opens in an urban landscape (in London) in down to earth, black and white in the rain photographed from within a moving car. The action or drama swiftly moves into a series of interiors – offices, conference rooms, flats, dancehalls, pubs, and even Tube carriages representing the protagonist’s working life and leisure time. These are broken up with the sequence of the testing of the Reeves Gun on Salisbury Plain and, towards the close, a bomb disposal sequence on the open pebbles of Chesil Beach which zero in on the small details – faces, hands, tools such as wrenches and the bomb itself, similar in size and appearance to a thermos flask. All this lends the film a feeling of claustrophobia throughout, and in that sense prefigures Peeping Tom, another urban film that although in colour also takes place largely in sealed off, interior spaces (film studios, houses, flats).

Sammy (David Farrar from Black Narcissus) possesses both a brilliant technical mind and a weakness for alcohol. His long-suffering girlfriend Susan (Kathleen Byron, also from Black Narcissus) is the secretary in the department where he works and lives across the hallway from the flat where he lives. Outside of working hours, Sammy is often to be found down the local pub (with a barman played by a pre-stardom Sid James), except for Wednesday nights when he and Susan hit the local restaurant / dancehall with its resident jazz band (Ted Heath’s Kenny Baker Swing Group). He has a false leg, which causes him a great deal of pain, and doesn’t dance. He carries on stoically, but Susan would prefer it if he would embrace life rather than feeling sorry for himself.

In his flat is a bottle of whisky allegedly being kept for celebrating when the Allies win the war, but at times the temptation not to indulge proves too much. Susan is well aware of this, knows that sometimes the booze is the only thing that helps him manage to keep on living and, from time to time, even suggests he have a drink.

Their relationship, although it’s never explicitly stated, is that they are a couple living in two more or less adjacent flats, which goes some way to makes the film feel particularly modern. Both Farrar and Byron’s performances impress; you get a real feel for the trials and tribulations of a couple when one of them is an alcoholic with a low sense of self-worth while the other is doing everything in her power to make their relationship work, even if that means going against conventional wisdom and pandering to her partner’s alcohol addiction.

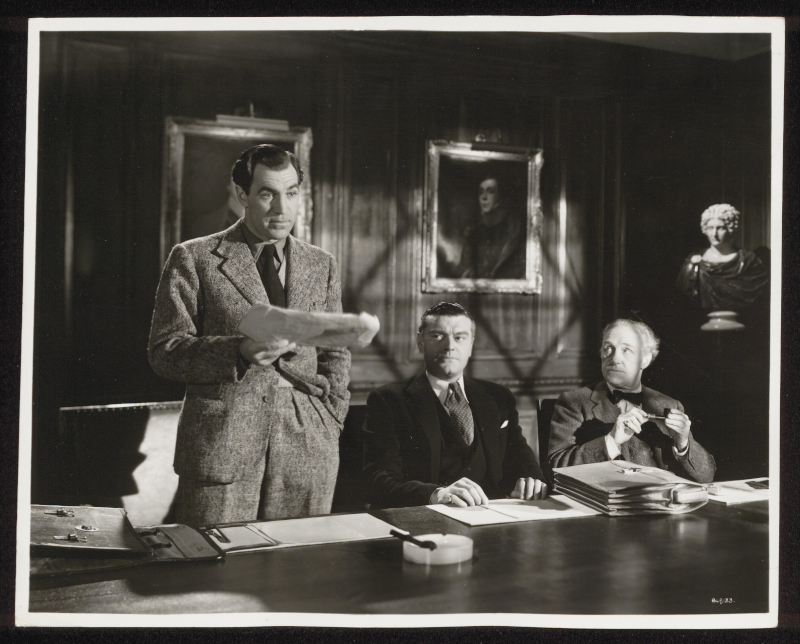

As in Nigel Balchin’s novel, office politics are often to the fore, something Sammy is not very good at. He finds himself frequently at odds with incoming boss Waring (Jack Hawkins) tasked with promoting the department to government, who Sammy despises as someone who should have gone into advertising. There is contact with various civil servants and ministers, who are shown as lacking in knowledge of exactly what it is the department does and are not looked favourably. He is much more at ease with his scientist head of department Professor Mair (Milton Rosmer) and as one of the more senior figures in the small research lab is concerned for the welfare of his less seasoned colleagues, among them Taylor (Cyril Cusack) who is experiencing difficulties in his relationship with his wife.

If the film is never whimsical as such, certain inventive touches mark it out very much as a Powell and Pressburger film. There’s a Whitehall conference where those present must suffer the sound of workmen drilling intermittently outside the window, something often endured by British people in real life but rarely portrayed in films. On one level, it makes not a jot of difference to the plot, yet it most definitely contributes to an overall malaise in the setting.

While the whole is solid and engaging, two sequences are particularly outstanding.

In one, Sammy is alone in the flat awaiting the arrival of Susan. The bottle of whiskey looms ever larger, as does the ticking of the clock when she doesn’t show. Powell and Pressburger turn this into something worthy of the German expressionists, as first through clever positioning of the whisky bottle and the actors, later through subtle exploitation of images of clocks, and finally with visuals involving Sammy and a giant whisky bottle, the whisky slowly comes to dominate his immediate horizon until he succumbs, opens it and drinks. Some of the credit for this sequence must go to the compositions of cinematographer Christopher Challis, here serving in that role for the first time on an Archers picture (and featured in a fascinating 20-minute interview on his work for the filmmaking duo on the disc). He credits Powell’s visual brilliance for making the sequence work, but I’d be willing to bet that a good part of what went into making the sequence so effective was Pressburger’s extraordinary facility for scripting sequences and stories so that they both did their job in script terms and constantly surprised audiences.

In the other, paying off a script thread that runs through the film via the character of Captain Stuart (Michael Gough) about a particularly nasty type of German bomb that has been killing curious children, Sammy must defuse the second of two bombs after the first has blown up Stuart. We don’t see the explosion, but instead are read a sizeable portion of the notes Stuart dictated to an ATS Corporal (Renée Ascherson in an extraordinary, one scene performance) on the other end of a field radio up to the point the bomb blew up as she reads them back to Sammy after he has arrived at the site. The tension of the bomb disposal scene is palpable, with Sammy lying on the pebbles of Chesil Beach doing the work while everyone else takes cover from the potential blast should he not succeed. It’s hard to think of another scene like it that is anything like as powerful anywhere in the movies.

The film was the first Archers production after the pair fell out with Rank on The Red Shoes, made under the umbrella of Korda’s London Films. There;’s the sense of Powell and Pressburger fiercely defending their position as independent producers, making the films they wanted to make the way they wanted to make them, and as such, for this writer, although it’s a very different film from what preceded it, it remains one of the Archers’ stronger films. It’s probably never looked as good as it does here in StudioCanal’s brand new 4K restoration.

The Small Back Room played at BFI Southbank on Tuesday, May 28th prior to release on Blu-ray, DVD and Digital on Monday, June 3rd.