Transcript of interview from 1994 with actress Julie Delpy on Three Colours: White. She plays the short but pivotal role of the main character’s ex-wife, whose appearances bookend the film. At the time, the third film in the trilogy had yet to be screened to press.

She was based in LA., on which subject our conversation started:

“I’m doing everything. Both European and American films. My project there is similar to what I was doing before – American films and European films and co-productions, whatever. I’m not trying to see where I should be, I’m just trying to find something that I like to do. It’s a bigger choice when you’re over there.”

Three Colours: White is very much a European film – not a film set in any one country but partly in Paris and largely in Poland. How did she get involved?

“I knew Kieślowski, I met him a few times, he’s a friend of Agnieszka Holland with whom I had worked on Europa Europa. I had tested on The Double Life Of Veronique, but knew that I wouldn’t get that part because he told me before the casting began that I wasn’t right for it, but he wanted to audition me because he was thinking of something else later. So, I guess I didn’t have to do an audition for this as well to see how I would respond to his indications.”

“So, when he called me for this film, it’s not a huge part, but I’d heard that the three films which comprise this trilogy would be his last. So it would be the only opportunity I would have to work with him. He follows what he says, so obviously these’ll be his three last films.”

A pity.

“That’s the way it is. He may change his mind, but if by any chance he doesn’t, then at least I’ll have worked for him on this.”

So she was cast before any of the three films began shooting?

“Yes, because we shot everything on the same schedule. Everybody was cast at the beginning of the three films because they were going to be shot one after the other.”

Audiences will be amazed to see Juliette Binoche (from Blue) appear and disappear in White very briefly.

“Blue is the same – but the difference is you didn’t see White before Blue, so you didn’t notice.”

Did Julie appear in Blue?

“Oh, from far away with my husband when I’m sitting next to the pregnant girl who’s the lover of Juliette’s husband. She’s my lawyer.”

(2023 editor’s note. Florence Pernel, the actress who plays this character, is credited in Three Colours: White, but I haven’t been able to spot her in the courtroom scene. She must have been there on the set, but perhaps her scenes were cut and the surviving scenes framed in a way that doesn’t include her.)

Does Julie turn up in the third film too?

“Yes, in a special scene at the end – which Kieślowski doesn’t want anyone to talk about beforehand.”

(2023 additional editor’s note, just after rewatching Three Colours: Red. The unexpected. almost deus-ex-machina ending (or is it?) exhibits a strange parallel to that of Blind Chance in the way that both bring together three separate plot strands via a cataclysmic event. In a way, I wish I’d asked Kieślowski about that in 1994, but because it’s about the ending, one can only say so much without ruining it for those watching the film(s) for the first time. And I’m not prepared to do that.)

On Blue, Kieślowski was keen to stress how different the three films were from each other. I was very surprised by just how different White is from Blue.

“Well, it’s a totally different thing. They are three films, but they have very little links to one another in the style and story and the way in which they’re filmed. But that’s what he wanted to do – what interested him certainly wasn’t to do the same thing over and over again.”

Which numerous filmmakers do. But it’s not a good idea.

“No, it’s not. He did well to do something very different – and in more of the style of a comedy.”

I was really surprised, actually, after it said that on the blurb. But it is lighter.

“There’s more going on, there’s more of a plot handle to the film.”

Surprising, nonetheless, that Kieślowski should label the film a comedy. Yes, in the sense of a happy ending, but in the modern sense of, this will make you laugh, well, it doesn’t.

“It’s not funny, it’s not going to make you laugh. It may make you smile. But it’s not going to make you laugh, no.”

What does she think of the film as it ended up? Was it much what she expected?

“Yes. I loved the script when I read it and was really happy with the film. Actually, I’m really happy with the film. As an actress, I’m a huge fan of films in general, I love to go to the cinematheque in Paris and go and see films all the time.”

This sounds refreshingly European.

“Yes. So, for me, when you know all the work of Kieślowski – Decalog and stuff. White is much more in this direction. Do you know his films at all?”

Yes – Decalog, Blind Chance…

“That’s his best – also my favourite film in the world, I love that film… It’s closer to this than some of the films he did before. To me, it was really nice to read the script, and I was happy when I saw the film because it’s got something about it reminds me of some of the Decalog.”

As in Blind Chance, Kieślowski uses so little to say so much. In White, when one sees the trunk on an airport conveyor belt. Immediately you know something’s in transit. Later on, you make connections with it, but there’s a lot in that opening image.

“And what I love about this film is that, in the same way as you sometimes read in a book, you feel intuition to imagine what you want about a character, the way they look. Or when you listen to music… This film’s very close to that because there’s a lot of background to the characters he doesn’t give you. Like, what happened before, why is she so angry at him? You know it, but you don’t see it, and you don’t see what’s going to happen afterwards because it’s the happy ending, but she’s still in prison, and he’s outside without an official identity.”

It doesn’t sound like a happy ending, though, when one describes it. (But I agree that it is.)

“It’s a happy ending, but the darkest happy ending ever made. So, it gives my imagination the freedom to operate. A lot of films do that for you, don’t give you that freedom to work that out yourself. Here, there’s a lot of things you really don’t know – what’s going to happen or what happened. Was she really having sex with someone else when he phoned and she was making the noise? You don’t know. There’s a lot of things you don’t know. That’s good – it takes you with him. Go into his mind to ask, was she really doing this or was she not? I feel that’s why I like the film. That’s why I did it.”

What’s the line “spoken” at the end with deaf and dumb language?

“I’m not sure that’s in a real language as such. It’s just, when I’m free, I don’t want to go away, I want to get married.”

The wedding ring on the finger.

“That was, when I’m free, I don’t want to go away, I want to stay with you and get married. But yes, part of it, I think, is deaf language. Funnily enough, that’s what the film’s talking about – how they both have a hard time communicating. Even more, when they talk a different language. But that aside, how in a couple it’s hard to understand each other. When they start to understand each other, maybe it’s because they can’t talk to each other but just make signs. They may have tried and solve things before the trial by talking about them, but they never succeeded. It’s only for the first time at the end they can understand each other.”

There’s a lot of strange stuff going on with him apparently speaking rudimentary French. In the trial, he talks in Polish; after the trial, he gets out and talks with her in French.

“But that’s just simple sentences. The actor who plays him, Zbigniew Zamachowski, learned French phonetically – he doesn’t speak it.”

Another strange recurring image in the film concerns the bust near hero Karol Karol’s Polish bedside.

“The bust almost resembles the Marianne, the French bust of Liberty. As in liberté, égalité, fraternité. French. It’s a woman. With a face exactly like the woman he has. His whole problem is that he idolises her too much.”

Because she’s French and therefore from the West rather than the non-former Communist Bloc.

“Yes, but then he breaks it. Even if Kieślowski doesn’t like people to say so, I think there’s a lot of symbols in this film. Tons of them. Really polished. I think that’s one of the symbols. There’s a ton of them. To see them all, you’d have to see the film twenty times because there’s a lot of tiny little ones in there.”

“Kieślowski doesn’t like to give people the keys. He doesn’t say much about the meaning of his films.”

“He’s very guarded with his answers. If he wasn’t Kieślowski, it would be almost insulting. To the press conference in Berlin, he was dismissive of the whole thing. But he’s right to make the symbols free for the audience to interpret as they wish. To give them the freedom of using their imagination that you’d get reading a book.”

Here it is.

“Just do what you want with it. It’s good to be that way.”

People had (rightly or wrongly) pegged the first film as “Liberty”. I was initially unsure as to whether this second one was supposed to be about equality or brotherhood. So far, however, the one value we’ve talked about in reference to White is, again, “liberty”. With reference to the statue representing “Liberty”.

“The three values are mixed within each of the three films. White is a colour. When I think of white, it reminds me that when I was in school in science as a little girl, they would show you all those colours on a little wheel, and you would spin it, and it would go white. So all the colours combine into the colour white. So that’s why there’s a lot of things in his films. Because white can be every colour. It’s blue and red also. It’s liberty and fraternity also.”

It may well relate also to mood; the associations Blue has are to do with nighttime, gloomy, those qualities. White, on the other hand, is bright and uplifting, and you see clearly what’s happening.

“When dark things happen, it’s always quick. You go from one thing to another, so you never get the chance to dwell on the dark elements…”

Clarity; things appear very clear.

“Even the way it’s shot is very clear. It doesn’t look like totally perfect. We can see the quality of the skin. It’s more real, I think, more like reality the way it’s shot.”

What is he going to do with Red?

“No idea.”

Red. Blood. Stop.

“I don’t know. Haven’t read the script.”

The films were shot in the order Blue, White, Red. When Kieślowski and I talked, he had shot but was still editing Red.

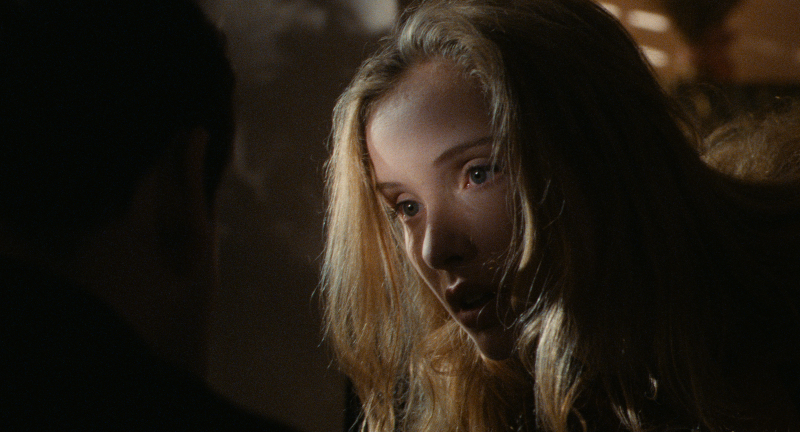

How far does Julie relate to Dominique?

“Apart from her being a woman, hardly at all – she’s very different from me. She’s very aggressive, and she does things that I wouldn’t consider doing – ever. She transfers her insecurity into anger. She’s close to me, and she’s far from me. She does things in the film that are far from me, of course. But about the anger… I could feel angry. Who wouldn’t in a situation like that. So the only level on which I relate to her is in her impulsive nature…”

That’s more or less how the situation with her husband arises. She thinks, this’ll work, then it doesn’t – and they’re stuck.

“Before you get into the film, I’m sure she can totally lock herself into this anger without even trying to solve it – because she’s very aggressive, among other things. But that’s part of her demeanour, of course. Kieślowski said to me, at the beginning of the film, try to be as mean as you can; and at the end of the film, just try to be yourself. That was not much – but it was enough for me to see what he wanted. If he chose me for the part, it’s because somehow he found qualities in her that were in me.”

It’s encouraging to know that he didn’t think her being mean and her being herself were different.

“No, because I’m not a mean person. He knows that. I’m a very impulsive person, and I’m very able to play some kinds of angry, aggressive characters. Although they’re not really me, I enjoy having those qualities in me. He knows that I enjoy playing mean and angry women. Bette Davis rather than a sweet Jayne Mansfield character.”

Did she enjoy setting the curtains on fire?

“I actually didn’t like it – I was really afraid to be inside. That required special effects, since curtains don’t burn that easily. I was going, “aaaaahh!” just before and “aaaaahh!” just after because I’m really careful, and I was really afraid. I almost burned my hand. That’s not my favourite type of thing I like to do as an actress – I’d rather do other things.”

Not, then, an actress who enjoys doing her own stunts. Not that this is exactly rolling around being covered in fire.

“Well, I had to do it.”

It’s not something one could bring a stunt double in to do.

“I never used a stunt double, I think. Oh, yes, yes, Very, very interesting. But that’s okay, a curtain on fire. In this line of work, it’s just one of those things you have to do.”

When you see it in the film, it’s quite shocking.

“I like that kind of scene of action. When I read the script, I thought, my God, this character is like an angry cat. Not a woman. Actually, for me, it’s always a challenge to do smaller parts. It’s much more difficult, in fact, because you have to give the meaning of the character in one scene or a few scenes. More time to develop the character is less demanding. And I guess that’s why a lot of actors that just like to act, just for the acting, will do small parts. Even great actors like Christopher Walken. It’s always fun to do that kind of character – very angry.”

We discuss – and she at length enthuses about – Walken and Hopper’s joint scene in True Romance.

“It’s just close up / close up with that dialogue. Like this. Dennis Hopper is likewise brilliant, playing the good guy, the good father, for once.”

Having to sketch the character with just a few scenes feels very much like the way this film is put together. With a very slight story (and little else), it’s very precisely put down on film.

“With the character of Mikolaj you can see exactly who he is and could show exactly what this character is thinking. It applies to his brother too. You really feel who he is. Funny how Krystof in a few scenes can really express what kind of person this is. That’s very rare. You remember the brother and a lot of other little characters. Every face you remember; he gives them soul.”

Did she feel the film was more about any of the three French values – liberté, égalité, fraternité (liberty, equality, brotherhood) – in particular?

“It’s a very Kieślowski interpretation of those values. He’s right because if you want to do a clear, separate interpretation of each value, it doesn’t mean much. It’s better to do good work. So I don’t know. You’d have to ask him.”

Kieślowski seems to have set up a series of three interrelated puzzles. So he’s then engaging in games with the audience. Which implies he’s probably, to some degree, requiring people working with him to enter into those same games.

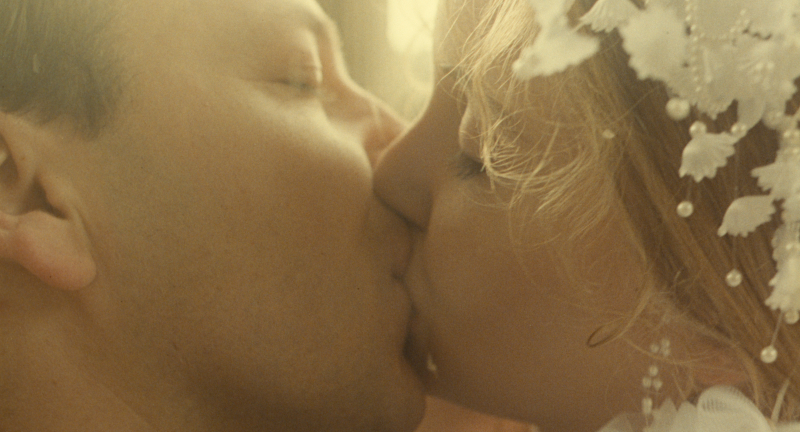

At what stage did they shoot the flashback footage of the wedding?

“That was done at the end of the Paris schedule. Took a few hours. It’s a very important scene too because it was their last beautiful moment. Because after that it was a nightmare.”

But Kieślowski avoids the cliché of starting with them getting married.

“The suitcase provides the first shot of the film. That’s good, to not respect chronological time sequence, to put the suitcase at the beginning and the white wedding memory scattered throughout the film in different places.”

You remember it right at the end, when it turns up again as one of the final images of the film. Which is weird after you’ve watched the guy doing all these things on his own and then pretending to die to get the woman to return. Then, here you are with this image of him getting married.

“He comes to regret what he did. This image is like a dream.”

Almost like a home movie, which can be seen as an intensely personal memory.

What comes next for the actress?

“Well, I’ve a few projects – but I chose three projects that have come up at the same time in the Spring, so I’m going to have to make a decision soon. I’ve known that for some time. I don’t want to talk about it, really, because I would have to tell you everything about the third project. I can end up doing only one of those.”

“Yeah, it is.”

White seems very much a film of what’s happening at the moment with its former Eastern Bloc in transition subject matter.

“It’s a caricature of what’s happening in former Eastern Bloc countries; maybe in five years it’ll be more realistic than it is now; maybe it’ll be possible to do everything he does. It’s much more a visionary film than anything else because I have the feeling that what it shows is much more the way things are going to go with capitalism running riot in those Eastern countries – it’s going to be more and more ruled by Mafia. It’s not yet – it’s beginning to be, and it’s getting worse all the time.”

Had she much experience of courts and judges and so forth prior to shooting the court scene at the film’s start?

“No. I’d never been in a court before. We just arrived in this location and did it in two days. It was very hard to get this particular place to shoot in Paris. It was only the first or second time anyone’s used it in a movie. A very famous, very busy place. The Palais de Justice in Paris. The centre of the court system in Paris; they use it for the biggest trials – political cases involving Arabs and so forth.”

They don’t use it for divorce cases?

“Yeah, but very rarely, I think. More for big cases.”

From speaking to Kieślowski, he was clearly at home in Poland. But in France, I got the impression he was much more of a foreigner feeling his way around.

“Yeah. He took some very representative French institutions; the Palais de Justice is not the most credible place for divorce. I mean, it is. But it’s very rare that it happens there because they go for higher profile presentations. But this film tends to go one step beyond reality. All the stuff Karol Karol does to get to Poland and the bad stuff he does and so forth. The main character is almost a pervert, going crazy; everything he does to get to Poland and everything, it’s always one step away from reality. It’s all a little further into this other area.”

A larger than life quality.

“It’s like a comedy, so you have to make things a little bigger. It’s a court, but it has to be the Palais de Justice. It’s revenge, but it has to be such a crazy thing. She’s mean, but she’s also going to burn his hair salon to the ground. So it’s real, but then it’s one step beyond to make it more alive. That’s what makes it more of a comedy. He goes back to Poland – but in a suitcase; it’s totally unbelievable. How somebody in a plane would be there – the X-ray would see there’s a body in there, whatever. That’s why it’s more of a comedy.”

It certainly marks the film out as different from Blue.

“It’s not like Blue at all. It’s different.”

ENDS