Director – Joseph Losey – 1963 – UK – Cert. 12 – 115m

*****

A highly capable working class manservant slowly takes control of his foppish, upper class master’s life – out in cinemas on Friday, September 10th

Barrett (Dirk Bogarde) enters the curiously unlocked Chelsea house of Tony (James Fox) to interview for the position of manservant. He finds the unkempt Tony asleep in a chair. He seems to fit Tony’s bill and gets the job. Tony got the house very cheap, although it’s in need of repair and decoration. Barrett has any number of useful suggestions, but Tony overrides one or two of them. A servant should know their place, after all.

At a club Tony tells his date Susan (Wendy Craig) that he’s involved in clearing jungle to build three cities. When he brings her back to the house, she finds her attempts at both romantic intimacy and imposing her ideas on his home consistently thwarted by Barrett’s intrusions.

Barrett secures a job for his “sister” Vera (Sarah Miles) as a maid. She is actually his lover. And she sets about seducing Tony. All of this will come to a head, with Tony throwing the pair of them out. However, Tony has come to rely on his manservant while Barrett can’t find another employer as good, and soon Barrett is back in the house.

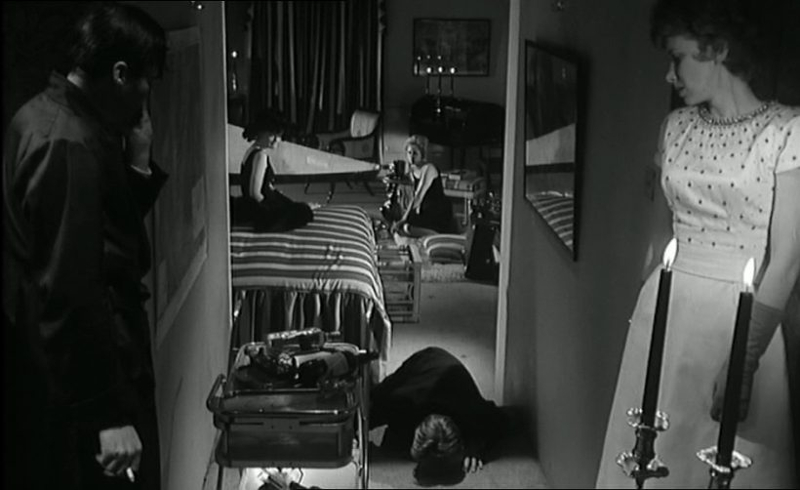

The power dynamic has shifted, however, and Barrett holds the upper hand, ordering Tony around. Where Tony previously brought Susan back to the house while Barrett surreptitiously moved his lover into the premises to lead Tony astray, now Tony is instigating orgies in the living room.

I’m not old enough to have seen the film at the time of its original release although it would have been fascinating to watch it as an adult with an audience of the day. (I’d never seen it before this 2021 4K restoration and re-release.) It can easily be bracketed in with the British social realist films of the late 1950s and early 1960s inspired by the Angry Young Men literary movement (Room At The Top, Jack Clayton, 1959; Saturday Night And Sunday Morning, Karel Reisz; 1960, The Loneliness Of The Long Distance Runner, Tony Richardson, 1962).

Yet its director was not British but American, a director no longer able to work in Hollywood thanks to his left-wing sympathies and the McCarthyist anti-Communist movement. In a curious reversal of the long tradition of immigrant directors making Hollywood movies with a social clarity that only a foreign viewpoint can bring, moving from the US to Britain, Losey is spot on with his view of the British class system.

The screenwriter Harold Pinter who adapted Robin Maugham’s novel most definitely had Angry Young Men credentials, though. And he turned in a script that provided the perfect vehicle for the cast. Bogarde is extraordinary as he slowly moves from deference to domination. Fox, in his first starring role, perfectly captures an upper class man who is used to being handed everything on a plate and suddenly finds himself completely out of his depth.

Perhaps the biggest revelation, looking at the film today for the first time, is Craig, with whom I’m familiar from her British sitcom career. She is magnificent as Fox’s heterosexual love interest, engaging in a battle of wills with Bogarde. Watching these three is like a masterclass in screen acting.

I want to be able to say the same thing about Sarah Miles, but I find her character clichéd. I fully admit I’m writing this with the benefit of hindsight, and perhaps her role was more effective when the film first appeared. And maybe it’s not entirely her fault. I’ve just praised both Pinter and Losey, but perhaps they too are partly to blame – one for writing the character the way he did, one for directing the actress the way he did. To me, the resulting performance hasn’t stood the test of time well and doesn’t rise beyond caricature. Remember, this film came out a year after the debut Bond movie Dr. No (Terence Young, 1962) with its predatory woman villain Miss Taro who must have genuinely shocked audiences at the time. By comparison, Vera is supposed to be the arch-manipulator, but she just comes across as an out of control slut. It really doesn’t work.

A curious side note. James Fox and Wendy Craig in this film have a similar facial structure and somehow reflect each other (a trope brilliantly exploited by the new poster and home video sleeve for the film). To the 21st Century viewer, both actors resemble David Bowie (as he styled himself in America in the late 1970s). Did he perhaps model himself on these two actors here?

Most of the drama takes place within Tony’s house, although the film opens out into his street and local area (which is in fact where it starts, with Barrett walking towards the house) and there are various memorable scenes outside – Tony with Susan in various nightclubs, pubs and well off friends’ stately homes, Barrett in a public phone box calling Vera while being hassled by four women who want to use it. The scenes in the house could so easily have turned the film into a boringly filmed, stagey affair, yet Losey manages to turn the interiors and the goings-on within them into compelling spectacle, thanks in no small part to remarkable black and white cinematography by Ealing veteran Douglas Slocombe, who among other things manages to pre-empt the use of light mediated by rain on a window pane of In Cold Blood (Richard Brooks, cinematography by Conrad Hall, 1967) by almost half a decade.

The sixties spawned at least one other movie in which the well off are brought down by someone who comes in and seduces them; Theorem (Pier Paulo Pasolini, 1968). More recently, The Servant’s social climbers infiltrating a wealthy elite family was a clear influence on Parasite (Bong Joon Ho, 2019) with director Bong even going so far as to issue a special black and white version of that film.

Admittedly, there are minor gaffes – Patrick Magee and Alun Owen have a lot of fun playing a bishop lording it over a curate in a restaurant, but again neither writer, director nor actors seem to have any understanding of what clergy are really like, and these characters don’t feel remotely true to life, even if their presence and those of other restaurant and pub clientele add nicely to the tapestry of the overall cast.

Elsewhere, the repeated Cleo Laine song on Tony’s record player, highly effective on first playing, gets a bit tiresome by its third playing. (Does Tony really only ever play this one record?) Some sex scenes feel coy by today’s more explicit standards, most notably the contrived and mannered, late orgy scene.

The film was made at a time when male homosexuality was a criminal offence in Britain, so it’s all the more remarkable that for the final reel, when Barrett seems to have beaten Susan in their battle of wills, that he and and Tony seem to have settled into a gay domestic relationship with Barrett as the dominant partner. For 1963, the portrayal of two bisexual men seems very daring and still packs quite a punch even today. It’s salutary to read the BBFC advice on the film: originally given an ‘X’ certificate (equivalent to today’s ‘18’), lowered to a ‘15’ for home video release in the late 1980s and now modified to ‘12a’ and ‘12’ for cinema and the forthcoming home video release respectively. Times change.

A fine jazz score by John Dankworth (who appears uncredited in a nightclub as part of a jazz band) helps anchor the piece in the early sixties.

Minor misgivings notwithstanding, the film overall holds up well today. A masterpiece, albeit a slightly flawed one in places.

The Servant is out in cinemas in the UK on Friday, September 10th.

Trailer (1963):

Trailer (2021 4K Restoration)

One reply on “The Servant”

love this review Jeremy. Gotta watch this. thanks. taran