Director – Phil Grabsky – 2022 – UK – Cert. 12a – 94m

*****

The story of American painter Edward Hopper, and how his artistic career was facilitated by his fellow artist wife Jo – originally out in UK cinemas on Tuesday, October 18th 2022, now available on home video (see bottom of review)

The latest entry in Grabsky’s generally excellent Exhibition On Screen series about art and artists covers the career of Edward Hopper to tie in with a major Hopper exhibition (Edward Hopper’s New York) at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. The big (and most welcome) surprise is that it charts not just Hopper’s life and work but also that of fellow artist Josephine Nivison, later his wife Josephine Nivison Hopper, whose career was largely eclipsed by his during his lifetime. To be fair, it doesn’t really go into her life before the point at which she became involved in his.

Hopper was born in 1882 and raised in the Nyack, New York house his parents had built (an enviable state, indicative of their and his time, which must surely influence one’s outlook on life). Religion and church were important to the Hoppers, but theirs was the brand of Christianity unafraid to engage with the outside world which at that time meant vast quantities of books and periodicals; the young Edward acquired a love of books from his avid reader father. The boy’s other interests included sailing (an evocative photograph of him aged 9 in a rowing boat riffs nicely off this fact) and going out armed with a sketchpad to draw. Creativity was encouraged, and there was no attempt to push the youngster into a particular career to ensure his financial well-being, as so often happens in families.

The Hoppers would often attend cultural events in nearby New York City, which led the boy to a fascination with approaching cities by train. Edward realised that his could explore his interests further by studying at the New York School of Art and Design, and did so, moving on to a decade and a half of working in illustration, a good earner but a medium and economic imperative he detested, claiming he was more interested in observing architecture.

He escaped with three trips to Paris, “the most beautiful city on Earth”. Where most young artists headed for the fleshpots of Montmartre, which area had a recent history of attracting great painters (at that time, Picasso and Cubism), Hopper’s family instead set him up in a Church Mission in Montparnasse where he was looked after by women who ensured he stayed away from the seedier side of life. He loved the place’s different light and its luminous shadows.

He embarked on a ten year romance with a female friend who did not reciprocate and found himself devastated when she married someone else and cut him off. His painting Summer Interior (1909) shows a partially-clad woman, naked from the waist down, slumped against a bed. This image of sexual trauma has been read as Hopper painting an image of his own emotional state.

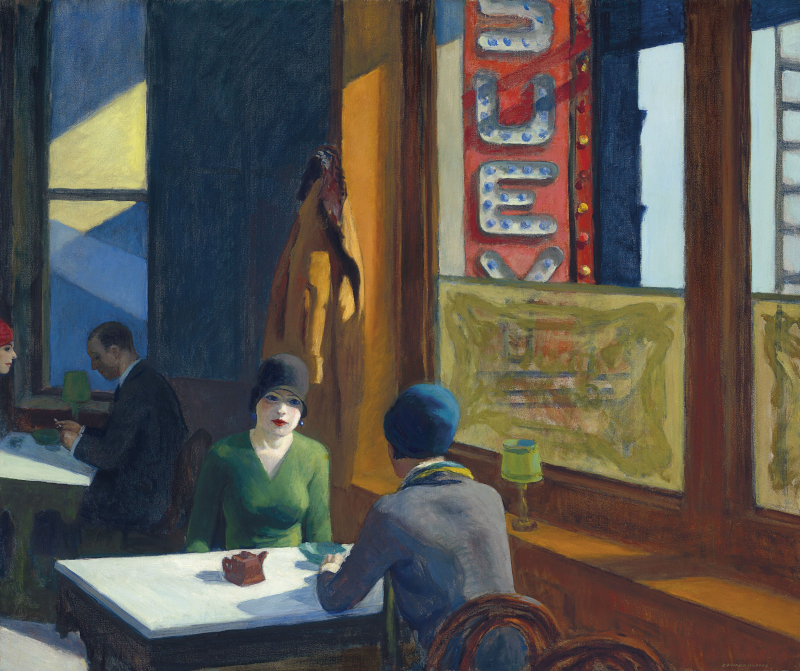

Back in New York, in 1913 he moved into an apartment in Washington Square, Greenwich village, Manhattan and a decade later became reacquainted with and subsequently (at her insistence) married former fellow art student Josephine Nivison, who was on the up as an artist. Jo was responsible for exposing him to galleries and making his career take off, although at the same time, hers stalled. They would sketch outside together, and he picked up from her an interest in watercolours. Jo kept extensive diaries, was effectively Edward’s business manager who logged everything he ever painted and write lengthy, highly detailed descriptions of his paintings..

She talked nine to the dozen while he was a man of few words, preferring to be left alone to paint. There was clearly benefit to both of them in their relationship, and they stayed together, yet at the same time the marriage was deeply problematic and painful. Josephine Nivison Hopper has, until recently, been largely excluded from art history, but this documentary suggest she deserves better. She was undeniably a profound influence on Edward, and outlived him.

As with his situation relative to other artists in Paris, throughout his life Edward very much ploughed his own furrow which had little to do with the art movements of the day. He was fascinated by buildings and architecture, and being something of a loner would often paint scenes with very few people, lone people or no people at all. Thus, pictures of houses and streets in New York didn’t represent the city’s hustle and bustle, more an imaginary urban landscape as if most or all of the people had been removed. As the century wore on, Washington Square saw increasing numbers of black people and a gig by Bob Dylan, but Hopper paid no attention.

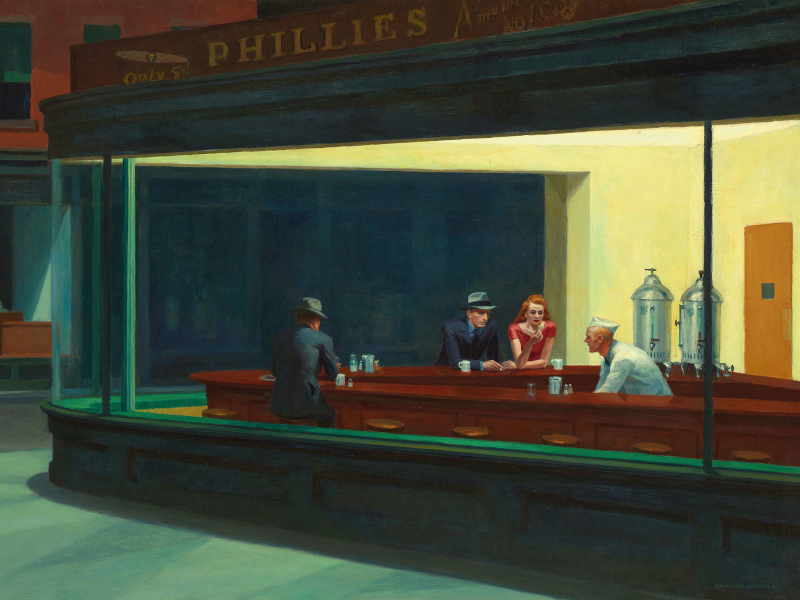

He and Jo bought a Summer house in South Truro on Cape Cod, Mass., and divided their time (and he the images in his paintings) between that location and the more urban New York. His paintings are a mixture of studies of buildings, noted for their remarkable and distinctive observations of light and shade, and senses featuring small numbers of protagonists that can be read as still image narratives. One of the former is House By The Railroad (1925), a clear influence on the design (and perhaps even the concept) of mother’s house in Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960), something out of which Edward apparently got a kick. One of the latter is his best known image Nighthawks (1942) of a man and a woman in a diner at night, with a man behind the counter serving, another man seated on another part of the counter and no discernible way in (although the film fails to mention that this could simply lie beyond the right edge of the frame).

Something else the film doesn’t mention – at least not verbally, because you can certainly see it in the images not only of Hopper’s paintings, but also some of the shot sequences establishing particular areas where he or he and Jo lived – is an influence on director David Lynch. There are moments when you could be watching the opening of Blue Velvet (Lynch, 1986) with its houses, picket fences and images of small town America. And there are numerous Hopper paintings here (and the film showcases an extensive selection of them) that you look at and immediately recall shots or moments from Lynch’s films, in spirit if not in actuality.

America is obviously a huge place in which it’s possible to live in a place hermetically sealed off from the rest of the world. Edward’s time in Paris notwithstanding, the Hoppers lived in parts of New York and parts of Mass. that furnished them with enough interest that they didn’t need to lock beyond that. It’s notable that almost none of the figures in his pictures are coloured (there is one composition featuring a black woman, which is discussed at “non-political”) and that despite his time in Paris, no mention is made of the impact on France of the First World War (presumably because it didn’t impinge on Edward’s life in any way).

Leaving aside such considerations, Edward Hopper’s work has clearly resonated with the art world in both the US and internationally, and this documentary provides a terrific introduction to it. That much, I expected before viewing. But I think it’s a much better film than that, because of the way it engages and to some extent interrogates introverts, sexual relations and marriage and discusses the role of the painter Edward Hopper as part of a partnership (Edward and Jo), not to mention its coverage of hitherto largely neglected Josephine Nivison Hopper. A must see.

Hopper: An American Love Story was out in cinemas in the UK on Tuesday, October 18th 2022, now available on home video here. A major Hopper exhibition Edward Hopper’s New York is at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York from Saturday, October 22nd 2022 to Thursday, March 23rd 2023.

Trailer: