Director – Alex Garland – 2022 – UK – Cert. 15 – 100m

***

An urban woman dealing with separation and bereavement encounters several men with the same face in an English village – out in cinemas on Wednesday, June 1st

A face passes before the eyes of Harper (Jessie Buckley) as her husband James (Paapa Essiedu) falls to his death from the balcony above their London flat. It’s the Spring. She drives to a house in the country – strictly speaking, in a small rural village – which she’s rented for two weeks to get away from it all.

There, she meets well-to-do landlord Geoffrey (Rory Kinnear) who shows her round the property and hands over the keys. He’s an affable and chivalrous sort of chap who insists of bringing her bags in from the car and can’t stop talking; he might have walked straight in from the previous century or even the one before. He mentions that the TV reception can be a bit iffy, especially when it’s raining, and also recommends a visit to the village pub.

She’s glad when he’s left and promptly calls her partner Riley (Gayle Rankin), who she will be in touch with this way on and off throughout the narrative and who will eventually drive over to see her, the only time we ever see Riley in the flesh. The mobile phone signal is unreliable and prone to cutting out.

The narrative is punctured with flashbacks of her and James’ disintegrating marriage relationship. It might be a single scene on a single day but it feels like a story that happened in pieces over a longer period of time. He warns her he might commit suicide. She counters that it’s outrageous for him to attempt to manipulate her in this way. He hits her face. She goes berserk and ejects him from the front door of the flat. She finds him prostrate like a tableau on the railings in the street outside their apartment block after seeing him fall, his hand and wrist pierced (almost like the familiar, crucified Christ portrayed in so much Western art) on the pointy bit at the top of the railings.

Harper goes out for a walk. She doesn’t really look dressed for it in her city boots and raincoat. Through the forest. The vegetation is lush and wet and fecund. She follows the old, abandoned rail tracks. Finds a tunnel. Shouts sound. Discovers the echo, sings a few notes, lets the echo play around with them like a looping device. Is in the moment, improvising, composing. (We don’t know much about her, but we later see her playing the piano in the house’s piano room, an instrument she earlier denied to Geoffrey that she can play. So she is clearly possessed of some musical ability.)

And then she notices the man sitting at the other end of the tunnel. He gets up. He starts moving towards her. There’s no suggestion as to his intentions either way, but she freaks and runs away. She loses him. She crosses a fence into a field (something you’re not supposed to do because you might not have right of way, and there might be good reasons for this, for instance if a farmer is protecting grazing livestock, or that livestock is potentially dangerous, for instance bulls). She crosses the field to an old, abandoned farmhouse complex. She looks around. She leaves. At some point, she becomes aware of the man (Rory Kinnear again) outside the ruined buildings. He is completely naked and is staring at her.

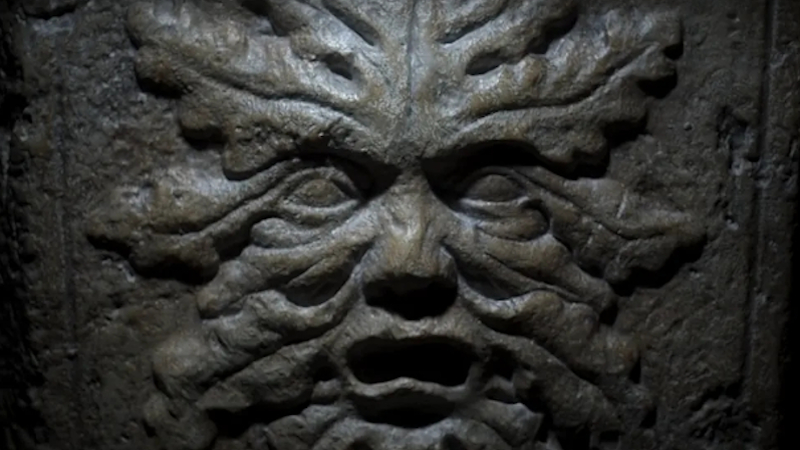

Later, Harper visits the local church, where a masked, young lad Samuel (Zak Rothera-Oxley augmented with the CG grafted-on face of Kinnear) asks her to play Hide and Seek, which she declines, for which refusal he calls her names. She goes inside where there are floral arrangements on each side of the altar and a font decorated on one side with the face of the green man and on the other with the full squatting figure of sheela-na-gig, a female gesturing to her exposed vulva. Two counterpointed images of male and female, natural, naked and fecund.

She is clearly in a bad way and audibly expresses her grief. The vicar (Kinnear again) doesn’t intrude, but catches up with her outside, rescuing her from Samuel who is verbally giving her a hard time. They sit on a bench by the church and the vicar speaks comforting words about his bereavement situation, momentarily resting his hand on her knee. She walks off in disgust when he suggests she might have driven her late husband to suicide.

She’s showing Riley round her rented house via smartphone when the naked man shows up in the garden outside the window. She’s talking to Riley for quite a while before spotting him. She calls the police about this “stalker” who arrive almost immediately and arrest the man: the local PC (Kinnear yet again) and WPC (Sarah Twomey). The latter sits and talks with her, to calm and reassure her. Later she visits the pub where she runs into Geoffrey (doing the crossword) and the PC who tells her that the man was harmless so they had to let him go, there being no evidence of any wrongdoing. Also in the pub are two local farmworkers (yet more parts played by Kinnear).

Various men (those played by Kinnear) attempt to gain entry to the rented house. The first puts his arm through the letterbox after she’s locked the door. She hides from the monsters sitting and crouching in a maze of kitchen cupboards reminiscent of a similar sequence in Jurassic Park, (Steven Spielberg, 1993). A seed floating in the air blows into Harper’s mouth and changes her demeanour, she first takes his hand then, reverting to type, knifes the arm. As the man pulls his arm out of the letter box, the blade slices it back to the join between the third and fourth finger. Thereafter, when any of these men (the Rory Kinnear characters) appear, they all exhibit this wound. Somehow, they are variations of the same person, birthing one another in a series of spectacular special effects scenarios.

Watching the film is a bizarre, disjointed experience. It doesn’t always make narrative sense, the whole being less than the sum of the parts. Yet, the parts remain fascinating. The performances (Buckley, the multiple Kinnears, Essiedu) and the cinematography by Rob Hardy are all striking. The figure of the bereaved woman in peril has been deployed effectively in countless thriller and horror films, among them Dead Calm (Philip Noyce, 1989) and The Descent (Neil Marshall, 2005) as has the British / Irish rural village / countryside in films including Straw Dogs (Sam Peckinpah, 1971), The Wicker Man (Robin Hardy, 1973) and Wake Wood (David Keating, 2009). The latter two are closer to the current outing in that they also deal with British rural folk religion and / or Paganism.

It may be closer to The Descent than anything else, albeit less coherent. That film featured female cavers, one bereaved, who (eventually) encounter (spoiler alert – skip to the next paragraph) a race of subterranean men.

Here in Men, the bereaved female protagonist in an alien setting encounters assorted male protagonists who turn out to be one and the same and who also, by their at least partially self-inflicted arm / hand wound, resemble the late, rejected husband whom the protagonist planned to divorce. Her current lesbian relationship is set against primal symbols of nature and man and woman, with images of dying and birthing males thrown in for good measure. According to the press blurb, writer-director Garland and his collaborators intend all this as a snapshot of where men and woman currently stand in relation to one another, but the fact that the story doesn’t make sense undermines this somewhat, at least to this writer.

An infuriating, failed, would-be masterpiece. That aims to do something hugely important and then, somehow, completely misses the mark.

Men is out in cinemas in the UK on Wednesday, June 1st.

Trailer: