Director – Mark Warmington – 2024 – UK – Cert. 12a – 100m

****

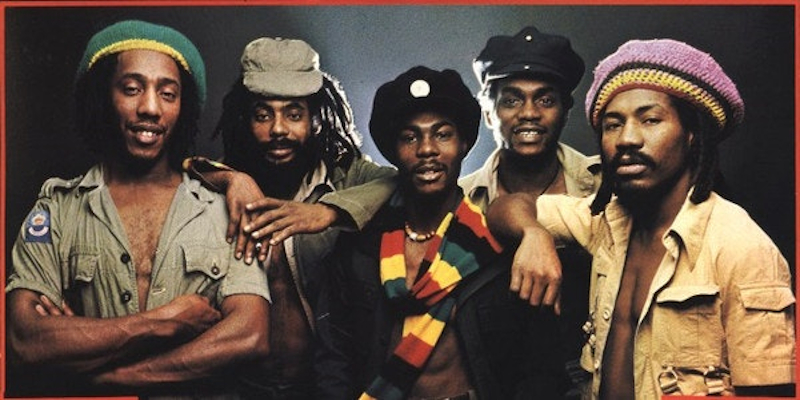

The story of Cimarons, the first British reggae band, who were formed in 1967 – out in UK cinemas on Thursday, October 3rd

As teenagers, they came from sun-soaked Jamaica to the UK to be confronted with a climate that was “rain, dull and gray.” In the 1960s, one of the areas that Jamaican immigrants came to in London was Harlesden, in Brent, and it was at Harlesden Methodist Church Youth Club in 1967 where Losely Guichy (guitar), Franklin Dunn (bass), Maurice Ellis (drums), and Carl Levi (organ) first met up and started playing music together, a site today commemorated with a blue plaque. They went through s number of singers over the years, notably Winston Reedy between 1974 and 1983.

By 1968 they were gigging as Cimarons. A performance at Paddington’s Q Club saw an A&R rep from Trojan Records in attendance, which led to a recording contract, their first album appearing in 1974, recorded in part as the Jamaican studio of the legendary Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry. Before that, they worked mainly as session musicians, appearing uncredited on numerous singles by black British reggae artists. The film isn’t particularly clear on the matter, but it’s mentioned that they lacked management and got hardly any royalties out of all this.

But if their business acumen wasn’t so strong, there is no denying that they could certainly play. As far as reggae in Britain goes, at the end of the sixties they appear to have been pretty much the only game in town and became the go to live backing band for Jamaican reggae artists visiting Britain. When Bob Marley came over in 1972, he was delighted to discover they knew all his songs and ended up using them on his UK dates that year.

Two years prior to that, they had already beaten him to being the first reggae band to play Ireland. In fact, they toured all over the place, including France and the Netherlands; they were the first reggae band to play Japan and Thailand. Although Irish and Jamaican music are very different, both cultures share a love of life and a history of oppression by the British, and Irish audiences took to them. In England, this means that Irish and Jamaican cultures are very close to one another, as indicated by the infamous British prohibition: “No blacks, no dogs, no Irish”.

Many of their songs either deal with oppression or with the idea that things will get better. The song Ship Ahoy (actually an O Jays song, although, again, this isn’t mentioned) deals with the transatlantic slave trade. They also did a song about celebrated Jamaican hero Paul Bogle.

When punk rock arrived in the mid to late 1970s, it had a stance of resistance against state oppression. As such, reggae acts were natural bedfellows to the movement. (By this time, there were more British reggae acts such as Steel Pulse and Dennis Bovell’s Matumbi.) Cimarons would often find themselves playing double bills with such bands as The Clash and Sham 69, supporting the latter on a UK tour.

An NBC interview clip shows John Lennon waxing enthusiastic about Jamaican reggae music. The Beatles connection doesn’t stop there. Cimarons fell in with Paul McCartney at one point – both Paul and then wife Linda were huge fans of reggae from her time living in Jamaica when she fell in love with the form. Paul worked with them on their album Reggaebility (1982), which they hoped would be their big breakthrough, but for whatever reason, the album slipped into obscurity. Times became hard, and at least one member of the band later took up a cleaning job to get by.

If the film is fairly perfunctory as a history of the band, where it scores is twofold. It spends time around the various band members and gets a real feel for them as people, and it captures a great deal of footage of the band after they started playing live again after a hiatus of some years in 2020, a plan initially scuppered by the Covid pandemic but subsequently bought to fruition.

A couple of the band members have sadly passed away – Maurice Ellis left us six weeks after being diagnosed with lung cancer during filming in 2021, and Losely Guichy gives a moving testimonial speech to his friend and fellow player at the latter’s funeral. In the closing minutes, singer Bobby Dego Davis is too ill to tour with them in Spain and passed during the film’s post-production process. Both, however, are captured on film here, along with the other members of the band.

The other asset is the performance footage, much of it recent, some of it much older archive material. Cimarons were clearly a terrific band whether working in the studio or playing live – they appear to have played a lot of large music festivals over the years – and the film does them a great service by running several live renditions of songs in their entirety, which are a joy to behold and, more importantly perhaps, listen to. Island Records recording engineer Tony Platt, who worked with them, having never come across them before the session, says he found the music so compelling that he was moving around to it in his chair as he worked. I defy you not to do the same in the cinema as you watch the Cimarons play live – and there’s a lot of that here.

Harder Than The Rock: The Cimarons Story is out in cinemas in the UK on Thursday, October 3rd.

Trailer: