Director – Hirokazu Kore-eda – 2023 – Japan – Cert. 12a – 126m

****

The mother of a school pupil believes her son is being abused by his teacher, who in turn protests his own innocence, yet the truth is more complex – out in UK cinemas on Friday, March 15th

A movie at once spellbinding and infuriating, as a seemingly straightforward narrative is retold from different points of view and shifts subtly as further details emerge. It’s not a film to see if you’re tired, as it requires considerable attention on the part of the audience.

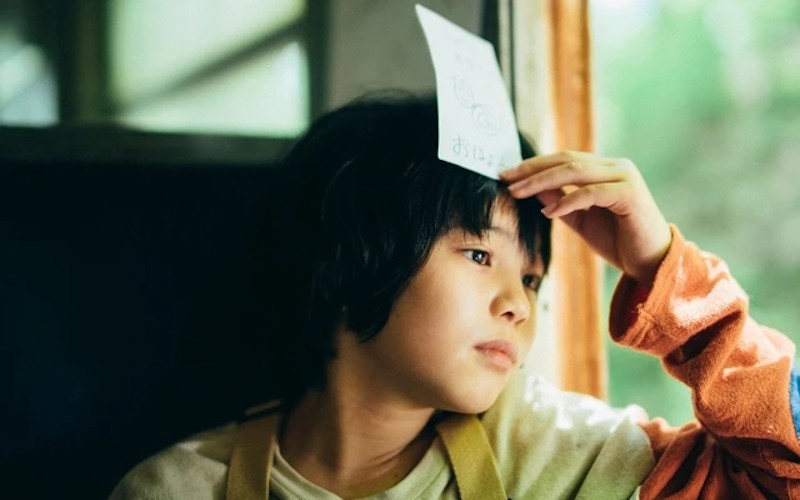

It starts off with a child’s feet walking along a patch of wasteland at night, sirens in the distance and then a blazing urban building which his single-parent mother Saori Mugino (Sakura Ando from Godzilla Minus One, 2023; Shoplifters, 2018 and Love Exposure, 2008) summons her son Minato (Soya Kurokawa) out onto their flat’s balcony to watch. Overheard conversation later suggests that not only was there a hostess bar on the third floor of the burning building, but that Minato’s teacher Mr. Hori (Eita Nagayama from Toshiaki Toyoda’s 9 Souls, 2003 and Blue Spring, 2001) used to go there. Somewhere in the middle of the film, Minato, who is a pupil at elementary school, and his classmate Yori (Hinata Hiiragi) play a game of Monster, which consists of images affixed to the forehead of each child and the question, “who is the monster”.

That’s perhaps the question with which to approach the whole film, because at various junctures, various different people will be thought of as monsters only to be considered differently later as the story and the motivation, guilt and innocence of the various characters involved undergo shifts that completely change the meaning of what’s going on. Certainly, a number of characters within the thriller / drama think that of various other characters, but as an audience member, you find yourself thinking that about most of the characters here at one point of another too, often modifying your opinion as new information about the situation slowly comes to light. That loosely places the film in a similar area to Kore-eda’s earlier crime / mystery / courtroom drama The Third Murder (2017).

It might be argued that the whole thing starts off conventionally enough in narrative terms, with a story about the mother Saori concerned that her son Minato is being abused by the inappropriately violent teacher Mr. Hori. However, looking at my description of the opening in the previous paragraph, I realise that the film doesn’t start off conventionally at all, throwing out titbits in kaleidoscopic fashion which may well be highly significant in the audience’s understanding of what is to follow.

It soon settles into something seemingly much more conventional, the “is my son being mistreated by his teacher” drama from the point of view of the worried mother. Why is Minato cutting off bits of his hair in the bathroom? What happened to the shoe he lost of a perfectly good pair? Why is he staying out so late (cue a sequence in which, following a sighting of Minato’s parked bike, Saori drives up to find her son in an old abandoned railway tunnel). Even then, it happily detours into other areas with mother and son celebrating the child’s late father’s birthday, offering a freshly baked favourite cake of his father’s to his father’s memorial shrine in the house. And a variant of the “is my son at the railway tunnel” sequence comes up later on, with Minato sheltering from a typhoon in a nearby abandoned railway carriage. I note in passing that a typhoon also featured in Kore-eda’s family relationships drama After The Storm (2016).

As Saori goes to a meeting with Minato’s school principal (Yuko Tanaka from One Night, Kazuya Shiraishi, 2019) to confront the problem, she is met with obfuscation. We will later see an aside in which a number of Mr.Hori’s male colleagues tell him to keep his head down and that some parents can be really difficult. Although there’s no doubt from what follows that he hit Minato on the nose – in a scene which marks a shift in viewpoint from Saori’s single mother to Mr.Hori’s teacher, he enters the classroom one day to find Minato throwing items about the room and immediately suspects the boy of bullying his classmate Yori. And this indicates an approach which may make the film hard to watch for some – the narrative will suddenly shift from one character’s viewpoint to another and flashback, all of it without warning. This is not a complaint, indeed it makes for a potentially compelling and engrossing film, yet it equally has the potential to throw the viewer into a state of confusion by moving too many elements around at once and causing them to lose their bearings, at least on a first viewing.

Later still, the film explores the narrative from the point of view of Minata himself, wherein we learn that the boy was not bullying his classmate: rather, the pair were good friends; indeed, Minata stuck up for Yori. There are glimpses of Yori’s home life; although seemingly a happy child in Minata’s company, he has to contend with an abusive, alcoholic father (Shido Nakamura) at home.

For most of his career, Kore-eda, who started off making documentaries, has scripted his narrative features himself. The current film is one of the exceptions, being scripted by TV screenwriter Yuji Sakamoto, and has a very different feel to Kore-eda-s self-penned movies. The writer makes great use of small details as he builds his story, which means that you have to pay great attention to catch exactly what’s going on and it may well be that this is a film that can’t really be fully taken in in one sitting, to which the viewer needs to return a number of times. That may be as much a curse as it is a blessing, because for some viewers, the struggle to work out what’s going on first time round may make them never want to watch it again, whereas others will want to come back again and again to fully appreciate its subtleties.

The film also boasts the final score of the late, legendary musician and composer Ryuichi Sakamoto, a subtle and gorgeous affair which in places is pared down to nothing more than a few deceptive simple notes on a piano.

This is Kore-eda’s first cinema movie in the Japanese language since his Cannes sensation Shoplifters (2018). It’s a striking film, likely to inspire a range of very different reactions, and a worthwhile addition to Kore-eda’s impressive filmography. At the same time, it’s also very different from what this extraordinary director usually does, and, while worth seeing, is not a terribly good entry point to his wider body of work.

Monster is out in cinemas in the UK on Friday, March 15th.

Trailer: