Director – Lars von Trier – 1996 – Denmark, Sweden, France, Norway, Finland, Italy, Germany, US – Cert. 18 – 160m

*****

NSFW.

A mentally vulnerable, young woman in an austere Scots religious community marries an outsider only for her husband to be severely injured working on an oil rig – out in a 4K restoration in UK cinemas on Friday, Aug 4th

Divided into a series of chapter headings in which locked off camera shots are accompanied by popular 1970s rock songs which cut off or fade out before they reach their end, like much of von Trier’s work this is not a film for the faint-hearted.

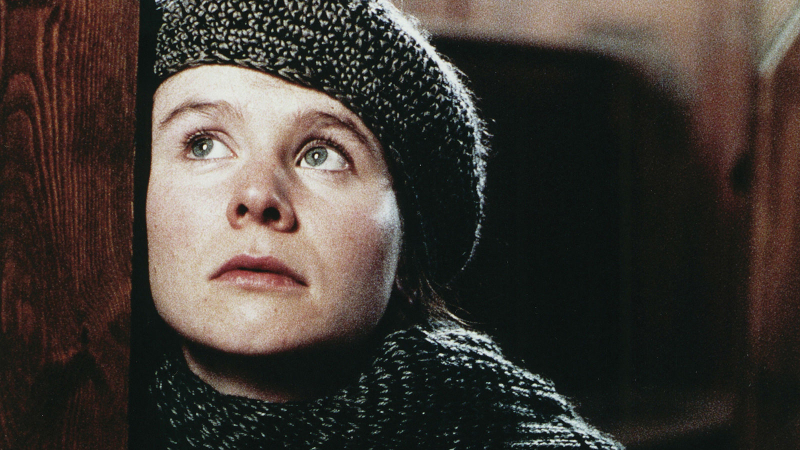

Young woman Bess McNeill (Emily Watson) is questioned by the priest (Jonathan Hackett) of the local, austere Calvinist community before its elders as to her understanding of matrimony and warned against entering into that institution with an outsider. Nevertheless, she proceeds to marry non-religious oil rig worker Jan Nyman (Stellan Skarsgård). Their relationship is extremely carnal and she is deliriously happy until the time comes, as it must, for Jan to return to work on the rig. She finds his absence almost unbearable.

Then disaster strikes, with Jan seriously injured in a rig accident whilst trying to help an injured fellow worker.

The extremely religious Bess often enters the kirk building to pray. Her prayers taking the form of dialogue in which she voices her concerns to God then voices his verbal responses to her as if he were immediately replying, or at least talking to her. Prior to the accident, she prayed for Jan to come home; after it, she blames herself for the accident, believing that it was the direct result of her request. Her prayer dialogues with God intermittently continue throughout the film as her behaviour becomes more and more extreme in her deranged attempts to heal Jan.

Her widowed sister-in-law and best friend Dodo (Katrin Cartlidge) – who is extremely fond of, concerned for and highly protective of Bess – gave a moving speech at the wedding reception in which she promised to kill Jan if he didn’t look after Bess. She works as a nurse at the local hospital, where Jan is bedridden. Having received a severe blow to the head, his recovery looks uncertain, with Dr. Richardson (Adrian Rawlins) diagnosing Jan as likely to be paralysed from the neck down for the rest of his life.

Frustrated by his inability to engage in physical carnality with Bess, Jan first encourages then persuades her to engage in sex with other men. She complies, motivated by both her love for her husband and the belief that such acts will help to cure him. She offers herself naked to Dr. Richardson who, like Dodo, is concerned for Bess’ well-being and refuses to take advantage of her. She then goes back to Jan and relays a not wholly convincing erotic fantasy narrative, naming Dr. Richardson.

Unperturbed by the doctor’s refusal to take part in her sex games, Bess masturbates a stranger at the back of a bus and when Jan objects in her recounting that that isn’t proper sex, she borrows some clothes to dress as a whore, picking up men in the local pub for sex outside. At some point, she carries out more sex acts than she relates to Jan, believing that in doing so she is helping save him and that through such acts she has a spiritual connection with her husband. The local prostitutes won’t let her join them on a boat to service sailors, so she instead secures passage to the big boat they won’t visit because of the misogynist habits of the men on board. She is violently abused and cut by a sadistic sailor (Udo Kier) and hospitalised. Later, after being bullied and pelted with stones by a gang of local boys, she once again visits the big boat…

The chapter headings and visuals lend a sense of literary respectability even as the rock songs suggest something much more anti-establishment and rebellious. This contradiction seems to embody something of what Von Trier is about: on the one hand, a serious filmmaker exploring both the human condition and the medium of cinema, on the other, a naughty child trying it on to find out what he can get away with. In both these activities, he is constantly pushing the boundaries which is perhaps why it’s both easy to admire him as a technical innovator in cinema and at the same time find his perspective to be disturbing, unpalatable and questionable.

Breaking The Waves, for example, is by no means an easy watch, but at the same time it’s so utterly compelling throughout that you can’t take your eyes off it. This is due in part to its bravura technique on so many levels. Although the piece was clearly scripted, the performances make much use of improvisation which cinematographer Robby Müller captures with his camera as if he were a documentary or news camera, with the image subsequently treated to make it look even rougher and grainier for a feeling of in your face verisimilitude. The wedding reception feels like someone has staged the event for real and sent in ENG cameras to capture it. Dodo’s speech is clearly scripted, but may well have been somewhat improvised too.

Skarsgård, Cartlidge, and Jean-Marc Barr (as Jan’s friend from work Terry) among others deliver striking performances, but the strongest performance here is from Emily Watson who in only the second film in her career embodies goodness, fragility, naivety, self-deception and much, much more. You immediately warm to her and, no matter how perverse and self-destructive her actions become, you stick with her in support wanting everything to work out even though it doesn’t look as if there’s any way it can, given her behaviour, as she makes all the wrong moves for all the right reasons. She’s delivered excellent performances in other films too, but never for another director with such a bold sense of both cinema and vision, and her work here and its cinematic treatment by von Trier and collaborators raises it to the jewel in the crown of her career to date.

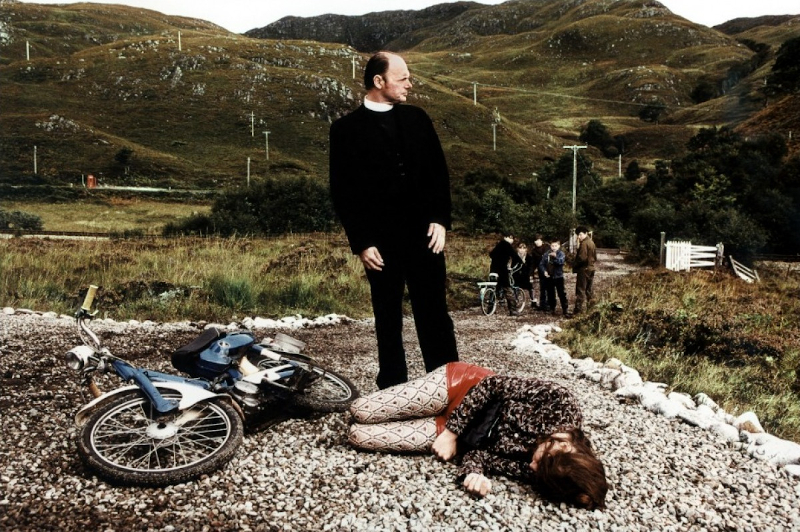

Von Trier’s treatment of this Calvinist community might reasonably be described as harsh but fair. This coast would be an unforgiving place to live at the best of times, and once the film has traversed the joyous sexual passion of Bess and Jan’s initial weeks of married bliss, it moves on to the worst of times, first with his absence and later with his injury. Before that, not only the dire warnings of the minister but also Dodo’s admonitions to Jan to look after Bess or else scarcely render the early days of the marriage paradise, yet Bess appears to be in a state of bliss even as the community and those around her have grave misgivings. Much is made of the male domination of religion, with women not allowed to speak in meetings, and an unforgiving spirit in which a deceased member of the community failing to live up to the community’s self-proscribed high moral standards is condemned to hell as sinners at his burial. When Bess later storms in to a male church meeting and speaks, “trying to understand”, she is cast out of the community for her pains, as much, one suspects, for her daring to speak as a woman as for any missteps in sexual behaviour she may have made.

That isn’t to let von Trier off the hook, though. His treatment of religion feels more like an outsider’s view than an insider’s, equating as he does here such things as prayer and faith with mental illness and a joyless austerity of existence. And the sexual material, while not particularly explicit, is extreme in its implications.

Both here and in many of his other films, there’s the sense that von Trier wants to see how far he can go, whether he will take people with him or offend them. Here, he seeks to explore the ‘goodness’ of his central character by pushing her into increasingly perverse sexual dealings. The cinema has long been a place where vicarious and aberrant behaviour can be explored on the screen, allowing us to watch and ponder a such things without them taking place for real (always assuming, of course, that they weren’t staged for real before the camera and then shot, which I’m pretty sure they weren’t in Breaking The Waves). However there’s a sense in which von Trier seems to wants to revel in such material and push our faces in it. He remains one of the great provocateurs of cinema. How far, and indeed on which occasions, that’s a good thing is a subject for deep, considerable and lengthy debate.

That said, whatever its limitations and virtues, some twenty-five years since it was originally released, Breaking The Waves remains one of von Trier’s strongest and most challenging movies.

Breaking The Waves is out in cinemas in a 4K restoration in the UK on Friday, Aug 4th as part of the season: Enduring Provocations: The Films Of Lars Von Trier.

Trailer (Enduring Provocations: The Films Of Lars Von Trier):