Directors – Axel Danielson, Maximilien Van Aertryck – 2023 – Norway, Sweden, Denmark – Cert. 15 – 88m

****

An idiosyncratic history of moving image technology and its increasingly pervasive role in human society, from camera obscura to smartphones and social media – out in UK cinemas on Friday, April 19th

To understand what this movie is about, which I’m not sure I did going in, you have to understand its title. The fantastic machine in question is, in part, the camera. That might lead you to anticipate a history of photography, but that’s not quite what this is about. You’d be forgiven for believing that, though, for the first few minutes when we see a contemporary, on the street, walk-in exhibit of the camera obscura or pinhole camera, a natural optical phenomenon whereby light passes through a simple pinhole onto a surface or screen beyond to recreate an inverted image of where the light came from. As a visitor marvels of the resultant, real time moving image of people outside the exhibit walking around, “it’s upside down”. As a human guide to the exhibition explains, that’s how the human eye works. Our brains correct the upside down image so that appears the right way up.

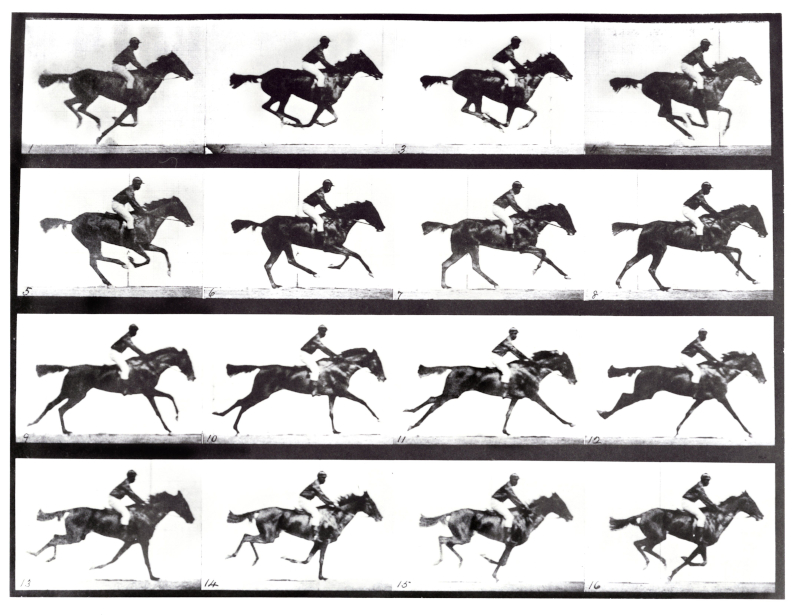

It’s less than two centuries since 1828, when the first still photographic image was captured and fixed on a flat plane, on which it could later be displayed. Passing briefly over such developments as the decrease in exposure time – it wasn’t long before the period to capture an image had been whittled down to as little as ten minutes – the next stop on this highly selective, whistle-stop tour is mid-nineteenth century US photographer Edweard Muybridge who, spurred on by such questions as, when a horse gallops, do all four hooves leave the ground as any one time?, used the camera to record numerous studies of human and animal bodies in motion. His moving camera produced serial stills rather than moving images, but it’s a simple enough job using later moving picture technology to reshoot his stills and by a combination of animation and persistence of vision turn his photographic studies into film clips of moving images. The tour is selective, because at this point, it makes no mention whatsoever of Muybridge’s French rival Étienne-Jules Marey, the self-styled chrono-photographer.

The narrative moves swiftly on, bypassing numerous developments in photography and quite a few in cinematography to alight on two of the progenitors of cinema, the Lumière brothers and Georges Méliès, both from Paris, France. By now, it is becoming clearer what this movie is to some extent about, a history of the moving image. But that’s not exactly what it’s about either.

The Lumières, the piece notes, pioneered a successful business model for funding films whereby they would find a crowd, shoot it on film and then charge people for the privilege of watching a film of themselves in the crowd. All this had an element of showmanship about it; there was something magical about watching moving images of workers leaving a factory, or a train arriving at a station and passengers disembarking.

The more theatrical Méliès essentially staged plays for the moving camera. The narrative here doesn’t dwell on his more fantastical scenarios, instead looking at his recording of The Coronation of Edward VII (1902). Today, we would take cameras to the event and record (and broadcast) it live, but Méliès didn’t do that; rather, he re-staged the whole ceremony with actors in his Paris studio leaving the King to remark, on seeing the film, what a fantastic machine. The film contained things that hadn’t taken place in the ceremony, something which particularly impressed the King. Curiously, The film omits to mention that today we would refer to this as ‘fake news’. It perhaps fits equally readily into the notion of fantasy, of which cinematic genre Méliès is rightly considered a pioneer.

You might expect the film to move on to the rise of Hollywood in the 1920s and the introduction of sound into motion pictures at the end of that decade, but instead it leaps forward to a chilling interview with the ageing Leni Riefenstahl talking about filming Nazi parades in the 1930s in terms of rhythm, precision and so on – technically all very impressive, but completely lacking as to any sense of the immorality or sheer evil of the regime her moving images both portrayed and, by implication, shored up and justified. It touches briefly on British producer Sidney Bernstein’s work for the Ministry of Information (MOI) trying to corral the footage shot by Allied cameramen entering the Nazi death camps into a feature film to show to the German people to make them aware of what had taken place under Hitler. (The ultimately abandoned 1945 production German Concentration Camps Factual Survey was completed as a restoration in 2014.)

After that, it leaps into the way the screen moved from picture houses to the home via the new medium of television. (I note with a degree of irony that the current documentary, a cinema release, is being released as such in the UK by the distributor with the corporate name of Picturehouse.) The central thesis being framed as about the moving image, rather than the moving image with sound, the documentary again bypasses developments in sound such as radio, telephony and the pre-smartphone mobile phone. And, for that matter, the internet. Although it deals with the latter in some fashion, by exploring the phenomenon of the viral video. As I said earlier, selective.

In a fascinating clip, television mogul Ted Turner talks about the medium as an escape from people’s everyday lives, citing the attraction of a show such as The Beverly Hillbillies (series, 1962-71) and explaining that if all the rolling news channels switched to playing this sort of material, he’d simply switch his content to a rolling news channel. News and entertainment, it seems, are interchangeable as content. Elsewhere, a news anchor admits that she and her colleagues occasionally refer to their news programme as “a show”.

Somewhere around this point, the documentary subtly shifts format from an historical narrative with voice over pulling a coherent stream of thought together to a jumble of images lacking any such framework making sense of it. This is the arrival of the smartphone and such websites as YouTube onto which people can upload clips they themselves have filmed. No longer is the broadcasting of moving images the exclusive purview of TV companies: now anyone can do it and anyone else can share it. And if you hit an emotional trigger whilst doing so – like the woman who sang a song standing on a table and fell off when it collapsed, unintentionally creating the world’s first viral video – you can reach enormous, global audiences.

People show themselves hanging off the side of buildings with thousands of feet below. People film a toddler’s traumatised reaction to Simba Dies in The Lion King (with the Disney film’s images whited out by glare, so there are no copyright issues). And at the close of the documentary, we return to pre-YouTube times, specifically 1977 and the specially chosen messages loaded onto the Voyager spacecraft to be read by any intelligent extra-terrestrial life it might encounter on its travels, images carefully curated to show a wide variety of human behaviour but nothing violent or disturbing. That exercise was carried out almost half a century ago.

Exactly what the documentary, particularly in its later stages, is trying to say remains unclear. The whole thing certainly functions as some sort of marker as to where human society and individuals now finds itself and find themselves, and it can certainly be described as a study of sorts of human beings, their technology and their relationship to the moving image. Perhaps it’s all too much for one film, and you could start from the same place and ended up with any myriad number of different films, each equally valid and each seeming to initially have something to say but concluding in a place of vapidity. Perhaps that’s the point; we now produce moving images at such an overwhelming rate that they have the potential to no longer mean anything. A terrifying concept.

Fantastic Machine is out in cinemas in the UK on Friday, April 19th.

Trailer: