Director – Wei Shujun – 2023 – China – Cert. 15 – 101m

**

A cop must solve a complex murder mystery his chief believes to be an open and shut case – out in UK cinemas on Friday, August 16th

A small boy with a toy gun plays cops and robbers in a deserted building, He opens doors like the protagonist of a Hollywood cop movie, looking for an armed criminal. And then he opens the door at the end of the corridor to reveal… a drop. The edge of a half demolished building, a building site with diggers.

This bravura opening is the high point of a film that combines a number of disparate elements in an attempt to construct a gritty police procedural murder mystery. However, it gets rather too caught up in many of these elements, and they swamp the narrative, which becomes incredibly tough to follow as a result. (This reviewer went back a second time to see if he liked it more on second viewing. He didn’t.)

A police chief (Tianlai Hou), who is also a keen table tennis player, encourages his force to get their merit recommendations in. This offers a fascinating glimpse into Communist China’s concept of community – you point out those who are making a useful contribution so that they can be rewarded. Which, in principle, sounds an excellent idea. And this idea crops up throughout (and provides a significant scene towards the close). Presumably, it scores points with China’s notorious censors and benefits the movie’s official promotion. Especially if they don’t look too closely at the film, which is actually quite critical of that whole system, suggesting that the authorities make up their minds who to reward, then give those rewards even when they are not really deserved.

Ma Zhe (Zhu Yilong from Lost in the Stars, Cui Rui, Liu Xiang, 2022), the cop in charge of the investigation, is seen at home with his wife (Chloe Maayan from The Wild Goose Lake, Diao Yi’nan, 2019) through the months of her pregnancy, attempting to be a good husband to her even when she goes completely off the emotional deep end. Attempts to integrate the cop’s home life into the main narrative feel clumsy and disjointed. It might have added something to our understanding of his character, but, in the event, it doesn’t.

Perhaps the cop’s home life could be a movie in itself, but what’s here feels far too much like an essay on how a good husband ought to behave and far too little like any sort of exploratory drama. And it has nothing whatsoever to do with the main thrust of the plot: you could completely take it out, and it wouldn’t make an iota of difference. Except perhaps to the appeased Chinese censors, who might then pay more attention to other elements here.

That main plot involves a series of murders which take place by the side of the river, and it rains a lot, with rain falling on the river reappearing on and off as a constant motif. The killer’s victims are taken by surprise because they know the killer as a friend and don’t suspect the perpetrator’s true nature – at least, not until it’s too late.

Ma and his assistant Xie (Linkai Tong) encounter various red herrings – a cassette tape which turns out, on its second side, to be a series of aural love letters and include a train whistle that helps the cops pinpoint where it was recorded, a secret love affair, a suspect who has a previous conviction for indecency. The cassette tape leads to lots of scenes of the policeman listening to it in his car, much like the poet listening to strange, otherworldly messages in Orphée (Jean Cocteau, 1950) but lacking the emotional resonance.

A good deal of the film takes place at night, and is lit with the school of lighting where certain scenes prove visibly difficult to see because they are shot in natural darkness. This limitation could have been turned into a virtue, but, alas, here it feels more like a limitation. It was shot on 16mm.

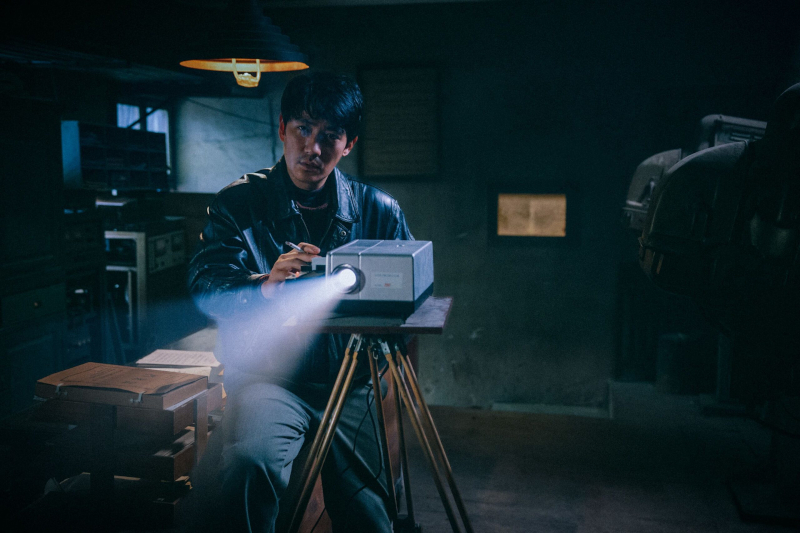

The cop heading up the investigation is given a decommissioned cinema as an office. He picks up an old roll of movie film and looks at a series of frames. Perhaps this is going somewhere interesting, you think. He puts it down on a surface, and that’s that. Later, he has a bizarre dream about the murder case in which, among other things, some movie equipment catches fire. The film doesn’t seem to know what to do with all this.

Stranger still, for a music soundtrack the film co-opts both Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata, re-using it until you’re sick of it, and, curiously, excerpts from Howard Shore’s radical, jangly electric guitar score for Crash (David Cronenberg, 1996). It’s like watching someone trying to cobble together a soundscape piecemeal from other works.

The source is the novella Mistakes By the River by acclaimed author Yu Hua. I’m guessing it works better as a book than this adaptation does, although it appears to be one of his lesser works.

As it happens, I saw this shortly after South Korean entry Next Sohee (July Jung, 2022), in part, at least, another film about a cop assigned an open and shut case which turns out not to be. For me, that extraordinary film is everything this pedestrian one isn’t.

Only the River Flows is out in cinemas in the UK on Friday, August 16th.

Trailer: