Director – Cary Joji Fukunaga – 2021 – UK – Cert. 12a – 163m

*****

We have all the time in the world. The new Bond movie gives Daniel Craig’s James Bond unexpected space to deal with human relationships and mortality – out on Blu-ray and DVD in the UK on Monday, December 20th and the US on Tuesday, December 21st

With its release delayed for over a year because of the global COVID-19 pandemic, Daniel Craig’s final screen outing as James Bond 007 finally arrives in UK cinemas, a week ahead of US release. Which is as it should be: Bond is British after all.

And yet, the plot sees Bond, now retired and living (like his late creator Ian Fleming towards the end of his life) in Jamaica, help out not MI6 but the CIA in the form of Felix Leiter (Jeffrey Wright in his third outing in the role opposite Craig’s Bond.).

The snowbound opening shows a little girl’s mother killed by a man wearing a Noh mask over a disfigured face; in the space of an edit, the little girl grows up to become Madeleine Swann (Léa Seydoux), previously Bond’s love interest in Spectre (Sam Mendes, 2015) and still together with him here.

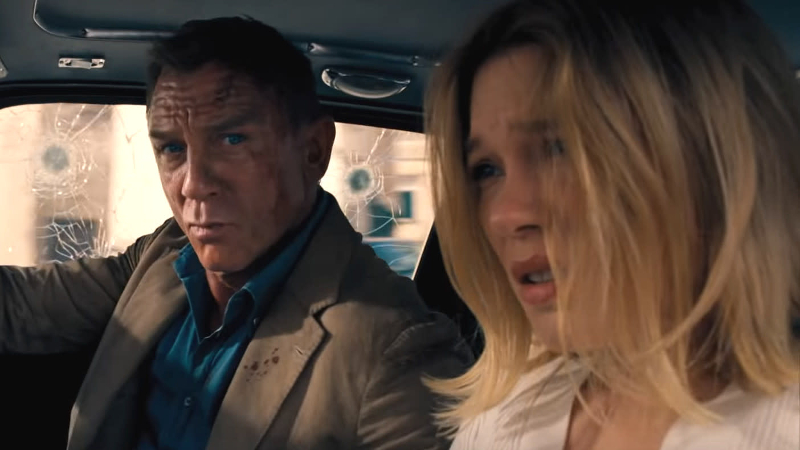

Driving through rural Italy to the ominous strains on the soundtrack of John Barry’s instrumental We Have All The Time In the World from the sixth and arguably best Bond movie On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (Peter Hunt, 1969), the couple talk about secrets and Bond resolves to finally tell her about Vesper Lynd (the woman who double-crossed him in both the book and Martin Campbell’s 2006 film of Casino Royale) if she’ll tell him about the secrets in her own troubled past. He takes time out to visit Vesper’s tomb where he is nearly killed by a Spectre bomb. As the pair escape Spectre’s assassins in the Aston Martin DB5, Bond comes to the conclusion that Madeleine had some involvement in the bombing.

All this backstory comes to bear on what follows five years later, when British government project Heracles is stolen apparently by Spectre but actually by Lyutsifer Safin (Rami Malek). The plot doesn’t get back to the facially disfigured Safin for ages, working its way up to him through Spectre agent (or is he?) Primo (Dali Benssalah), British-employed scientist and Heracles’ creator Valdo Obruchev (David Dencik) and US official Logan Ash (Billy Magnussen). M (Ralph Fiennes) has kept Heracles off the books and Bond is shocked to discover it was never shut down as he believes it should have been.

Heracles is a biological warfare agent with the ability to target specific people whilst bypassing others who can be selected by identity, ethnicity or other factors. This means it can be used to infect one person who becomes a carrier (with no symptoms or ill effects on them besides never being able to get rid of it) who can then fatally infect the designated target, an attribute with which the filmmakers have a lot of fun, and one of the smartest script ideas in spy movies since the face-ripping of Mission: Impossible II (John Woo, 2000). No Time To Die cleverly exploits Heracles to great dramatic effect. The only other Eon-produced Bond movie to deploy biological warfare is OHMSS, where Blofeld planned to use it to destroy home-grown, British food supplies.

Leiter makes an interesting remark about world leaders not getting on with one another, a veiled reference perhaps to Trump’s presidency in the US when the film was being made and was originally scheduled for release. A couple of years on, it’s strange watching a Bond film where the villain possesses the capability to cause a global pandemic when the real world outside of the movies is recovering from one. It doesn’t harm the film one iota, but it makes the subject matter feel perilously close to where we are now and adds a certain something the filmmakers can’t possibly have intended.

When Rami Malik finally appears centre stage, and especially when he delivers an homily attempting to justify himself to Bond, his villain is as powerful as I can remember in a Bond movie, right up there with Joseph Wiseman in the series’ debut movie Dr. No (Terence Young, 1962).

There are other surprises too, most of which would constitute spoilers, but one of which is already public knowledge, in that since Bond has officially retired, a new agent Nomi (Lashana Lynch) has been given the 007 designation. It says much for how far the UK has come in terms of ethnic and sexual equality that an establishment figure such as 007 can today be played by a black woman and be completely believable. However, she never feels like the new Bond, more like one of his many professional allies like the CIA’s Felix Leiter, and while you’re wondering how the next Bond movie is going to get around the fact she’s the new 007, somewhere in the middle of this one she tells M that he should give the numeric designation back to Bond now that he’s on active service again.

While much use is made of franchise MI6 regulars M, Moneypenny (Naomie Harris), Q (Ben Wishaw) and Tanner (Rory Kinnear), not to mention one sequence, kickboxing wonder Paloma (Ana de Armas), there’s something particularly gratifying here about the professional relationship between Fiennes’ M and Craig’s Bond, the latter considering the former has pursued a completely out of order course (not shutting down Heracles) in the interests of national security. Blofeld (Christoph Waltz) also appears, now an incarcerated prisoner who gets a face to face scene with Bond resembling something out of The Silence Of The Lambs (Jonathan Demme, 1991).

Safin, meanwhile, cultivates a garden of death populated with poisonous flowers, something Fleming created for the book of You Only Live Twice (but not used in Lewis Gilbert’s 1967 film which, while likewise set in Japan and featuring Blofeld, is a completely different story).

However, the previous Bond film that mostly casts its spirit over No Time To Die is OHMSS. That film’s bittersweet song We Have All The Time In the World, composed by Barry with lyrics by Hal David sung by Louis Armstrong, plays over the end credits and, still on the music front, a London riverside meeting between M and Bond as they work out how to go forward against the current threat is underscored by the music cue Over And Out used in OHMSS when a fleet of mafia-chartered helicopters heading towards Blofeld’s mountaintop lair, with Bond on board, are negotiating with air traffic control claiming to be a blood plasma mercy mission and therefore entitled to violate international air space.

Hollywood veteran Hans Zimmer, a huge admirer of Barry’s work for the franchise, provides NTTD’s score, so presumably the choice of reusing these OHMSS pieces is at least in part down to him. For me, no other composer has matched Barry’s achievement on the Bond films and, as with the franchise’s many other composers over the years, NTTD’s original score fails to produce the immediately memorable themes outside the iconic, redeployed Barry ones. Perhaps Zimmer’s score will improve with future viewings / listenings.

OHMSS is significant to NTTD in more ways than that, though. It’s one of the few Bond movies to truly exploit the character’s vulnerability and what it means to be human and mortal. In Fleming’s books, often towards the end, Bond often got physically damaged and ended up in hospital. That never seemed to happen in the pre-Craig Bond movies. Bond is minutes away from death in the last paragraph of Fleming’s From Russia With Love; in Terence Young’s 1963 film, Sean Connery’s Bond and Daniella Bianchi are messing about in a gondola In Venice as the end credits roll.

Taking its cue from Fleming, Craig’s Bond debut Casino Royale incorporated severe physical damage to Bond, keeping intact the book’s torture scene (and, indeed, its entire plot). It wasn’t quite the first time in the Bond movies: Pierce Brosnan’s swan song Die Another Day (Lee Tamahori, 2002), an original rather than a Fleming story, had already had Bond undergo torture… but that was all about Bond surviving because of his near-superhuman prowess rather than putting the torture and its effects centre stage, something Bond cinema audiences weren’t used to seeing.

In terms of mental and emotional trauma, Fleming pushed all this further in OHMSS than any other Bond book, and the film version effectively translated that element to the screen. Just as OHMSS dealt with inveterate womaniser Bond falling in love and getting married – with a tragic twist – so NTTD gives the character the space to deal with human relationships and mortality in unexpected ways. It’s Daniel Craig’s best Bond outing since Casino Royale, and a much better point to bow out of the franchise than the misjudged Spectre. Bond is well and truly back.

No Time To Die is nominated for Best Music (Original Song) in the 2021/22 (94th) Oscars as well as Best Sound, Best Visual Effects.

No Time To Die is out on Blu-ray and DVD in the UK on Monday, December 20th and the US on Tuesday, December 21st.

Trailers:

Release

2021

UK cinemas on Thursday, September 30th

US cinemas Friday, October 8th