Director – David Hinton – 2023 – US – Cert. 12a – 129m

*****

Martin Scorsese talks about the seminal British filmmaking duo, and how they inspired his own movies – out in UK cinemas on Friday, May 10th

As a child, Martin Scorsese suffered from asthma and would constantly find himself at home while other kids were outside playing. He often found himself sitting front of the black and white TV watching a show called Million Dollar Movie. This would show a movie a week, playing it several times, and it was at a time when US producers wouldn’t sell their movie rights to TV but British producers would. Consequently, he grew up watching black and white versions of old British movies.

The ones he particularly liked opened with an arrow hitting a target: “a production of the Archers. Written, produced and directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger.” When this logo and these names appeared, Scorsese always knew he was in good hands. He watched these movies over and over again whenever they were shown, and learned much of his filmmaking craft from them. The first of these films to which he thrilled didn’t have this logo: it was the Alexander Korda production of The Thief of Baghdad (Ludwig Berger, Michael Powell, Tim Whelan, 1940) and parts of the film have the unmistakeable Powell visual stamp.

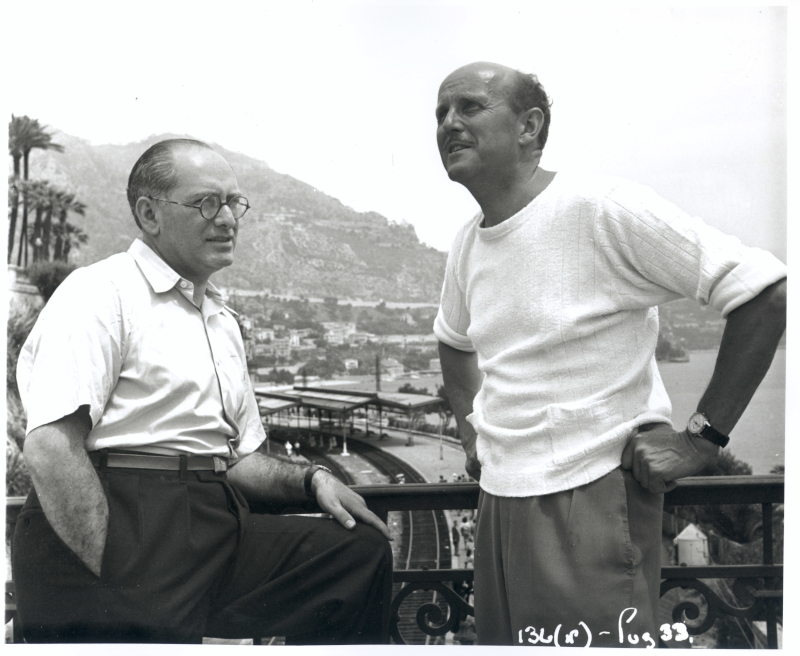

In the 1960s, there was precious little information about Powell and Pressburger; Scorsese had seen many of the films, albeit in black and white when some of them had been made in colour, but the two names behind the films were a complete mystery. In 1974, Scorsese visited London and asked around to see if anyone knew anything about Powell or Pressburger. Learning that Powell was living in a country cottage in Gloucestershire, he arranged a visit, which began a friendship which would last until Powell’s death in 1990. Scorsese sent Powell a copy of Mean Streets (1973), which Powell liked despite reservations about its colour scheme – “too much red”. Scorsese couldn’t bring himself to tell Powell that that overload of colour was something he’d picked up from Powell’s use of colour. Scorsese secured Powell a position in American Zoetrope, the New York company founded by Francis Coppola and George Lucas. Powell wrote his autobiography there and married Scorsese’s long-time editor Thelma Schoonmaker.

Rather than Powell and Scorsese’s friendship, this concentrates instead on Powell’s career and movies, notably (but not exclusively) those on which he and Emeric Pressburger shared a joint credit. Scorsese is forthcoming on how elements in the Archers’ films have influenced some in his own, such as the way the viewer is drawn inside the fifteen-minute ballet in The Red Shoes (1948) affected the immersive way he shot a boxing match in his own Raging Bull (1980). Aside from many nods to Scorsese’s own moviewatching habits, not least from those Million Dollar Movie years, he covers Powell and Pressbuger’s works in Powell chronological order, starting with the latter’s work as a general dogsbody on Rex Ingram pictures shot in the South of France, then working his way rapidly through Powell’s “quota quickies” (cheap and rapidly shot productions made under a scheme designed to give home-grown British talent a step-up), pausing at The Edge of the World (1937), a dramatic tale of the community on the Outer Hebridean island of Foula, and an improvement on everything Powell had done previously.

Pressburger comes into the frame when director Powell first met him on a script conference for the Alexander Korda production The Spy in Black (1939), where Emeric completely rewrote the script making some changes Powell would have made himself and more which he hadn’t thought of but with which he immediately agreed. He knew he had to work with Pressburger again, and soon the pair formed production company The Archers, whose films opened with an image of an arrow hitting a target. They produced half a dozen or so extraordinary films during the war.

Pressburger always wrote the first draft of their films before Powell got involved, and the pair tossed the ideas around, finding themselves largely in sync. They both produced, with Powell directing and Pressburger contributing ideas right the way through production.

Being a Hungarian Jew, Emeric was motivated to write promoting what was great about Europe prior to the rise of the Nazis. In the episodic 49th Parallel (1941), a stranded German U-boat crew must make their way across the British enemy territory of Canada to the safety of the (then) neutral United States by reaching and crossing the eponymous latitude. Pressburger inserts scene a scene of a German Hutterite community in which he made a point of differentiating the German, religious, Anabaptists from their Nazi visitors, whose ideals they do not share.

The Life And Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), loosely inspired by the popular newspaper cartoon character, was a tale of friendship between an Englishman and a German over several decades which Churchill hated but was unable to prevent going into production.

A Canterbury Tale (1944) was an attempt to show what exactly was it about England that was worth fighting for, opening with Chaucerian pilgrims, moving to a contemporary story about an American soldier and an English land girl and ending with great spiritual significance in Canterbury cathedral, a towering building in the middle of a bombed out city.

“i know where i’m going” (1945) tells a story of a woman marrying into money, but in order to get there, she must journey to a remote Scottish island. On the last leg of the journey, weather conditions get in the way and instead of her wealthy fiancé, she is confronted with a penniless local Laird.

A Matter of Life and Death (1946) opens with a bomber pilot crashing and a girl radio operator talking to him, knowing he is going to die. Except, owing to a bureaucratic cock-up in Heaven, he lands unharmed on the south coast, meets her and falls in love. As a result of which, he finds himself in a court case as to whether he should go up to Heaven or remain on Earth.

All these sprang from original stories by Pressburger, but after the war, his natural drive to write about Europe dried up and the pair began adapting novels. Black Narcissus (1947) concerns a group of nuns in a convent in the Himalayas, and the effect on them of a very earthy man. The Red Shoes, with its eponymous ballet adapted from Hans Christian Andersen, concerned a woman driven to dance, caught between her obsession for her art and her love for another human being.

J. Arthur Rank, who had backed the pair’s work and gave them creative freedom, thought The Red Shoes unmarketable and the Archers fell out with him. (He was wrong, since it became one of Rank’s most profitable films ever in the US and other non-British territories.) They tried to find backers elsewhere, returning to Korda for another adaptation The Small Back Room (1949) then running into problems remaking The Scarlet Pimpernel when Korda and Powell wanted to make two very different films. They scarcely fared better with Hollywood’s David O. Selznick on Gone to Earth (1950) which Selznick intended as a vehicle for his new bride, actress Jennifer Jones.

Following the fifteen-minute ballet section of The Red Shoes, the Archers made The Tales of Hoffmann (1951), an adaptation of Offenbach’s opera, working with the same crew. Powell and Pressburger’s working relationship dissolved in the fifties, though they remained lifelong friends. On his own, Powell would go on to make one final masterpiece in Peeping Tom (1960), reviled by the critics of the day for its psychopathic murderer subject matter and putting him out in the cold as far as the British film industry was concerned until his rehabilitation by Scorsese and others in the 1970s.

The whole documentary would sit well alongside A Personal Journey With Martin Scorsese Through American Movies (Martin Scorsese, Michael Henry Wilson, TV series, 1995) because it has a similar sensibility – basically, of Scorsese talking about movies with the aid of numerous film clips. However, it’s different from that because it’s obvious that the Powell and Pressburger films include many of his personal favourites.

Yet, there are some curious omissions – the main one being the complete absence of One of Our Aircraft is Missing (1942), which I imagine was cut to prune the running length – in which case, how about putting it back in for the inevitable Blu-ray release? Scorsese is also unexpectedly dismissive of what many consider the last great Powell and Pressburger film, the lightweight yet hugely enjoyable Oh, Rosalinda!! (1955), the Archers’ update of Mozart’s operetta Die Fliedermaus / The Bat to postwar Vienna, with costumes and art direction to die for.

Scorsese nevertheless remains both a huge Powell and Pressburger buff as well as an articulate and talented filmmaker in his own right, so his treatise on the Archers is a most welcome addition to film culture. If you know their work, this is the place to come for Scorsese’s take on them. If, on the other hand, you are completely unfamiliar with the films of two of Britain’s greatest filmmakers, this is a very good place to start.

Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger is out in cinemas in the UK on Friday, May 10th.

Trailer:

Clip: