Director – Martin Scorsese – 1991 – US – Cert. 18 – 128m

*****

A vicious ex-con seeks revenge on the family of the lawyer he sees responsible for his incarceration in prison – review from Strait – the Greenbelt Newspaper, March 1992.

Directed by Martin Scorsese with characteristic and frenetic energy, Cape Fear is his best movie in years. It ranks not so much alongside The Last Temptation of Christ (1988, file under embarrassing personal projects along with Until the End of the World, Wim Wenders, 1991) but rather as a companion piece to early collaborations with actor Robert De Niro like Mean Streets (1973), Taxi Driver (1976) and Raging Bull (1980).

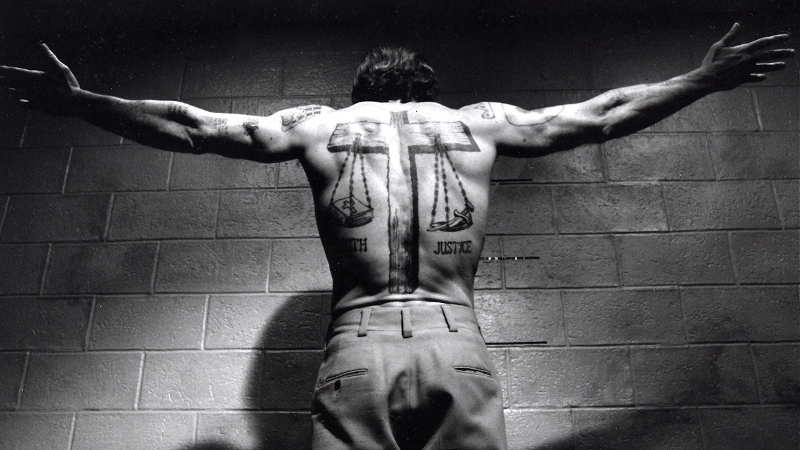

Here, the actor is first glimpsed from behind as a muscled torso tattooed with the Scales of Justice and numerous biblical verses. It’s a foretaste of things to come.

While the original Cape Fear (J. Lee Thompson, 1962) had Robert Mitchum as ex-con Max Cady who terrorises the lawyer (and his wife and daughter) responsible for his prosecution, Scorsese’s remake borrows religious elements from another Mitchum-as-villain vehicle, Night of the Hunter (Charles Laughton, 1955), in which his character justifies his actions in fundamentalist Christian terminology.

De Niro’s Cady is specifically a self-designated vessel of judgement upon the lawyer and his kin. Scorsese’s Catholic leanings further allow him to explore, at some depth, religious metaphysics external to the character of Cady himself.

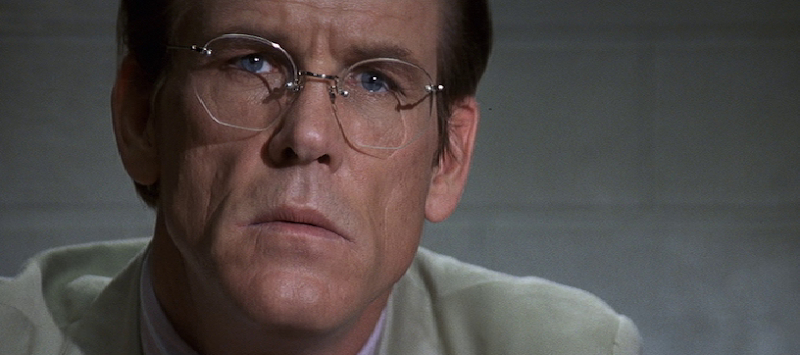

His lawyer victim Bowden (Nick Nolte) is seen studying the Book of Job in bed trying to understand what’s happening to him, while the film’s final confrontation (in which Cady tracks lawyer’s family to their houseboat on Cape Fear’s waters to wreak his judgement) is invested with full baptismal symbolism.

As the film’s appearance under the movie brat banner of Spielberg’s Amblin’ Entertainment suggests, this remake of Cape Fear is also highly movie-literate. Those familiar with the 1962 version will note not only the recurrence of not only Robert Mitchum but also Gregory Peck (the original’s lawyer) and Martin Balsam in peripheral roles, with the redeployment of the late Bernard Herrmann’s magnificent, brooding score an added plus.

Where the original movie dragged, Wesley Strick’s screenplay condenses; where the first skimmed events too quickly, this one expands them. Similar though the remake feels, only one scene – Cady at the airport registration desk – survives anything like intact from the original.

The source material is given subtle twists. Cady begins his campaign against the Bowdens’ teenage daughter (Juliette Lewis) by posing as her English teacher, sympathising with her parental antagonism, and making tender romantic advances towards her. (To make matters worse, he later slips her a copy of a sexually explicit Henry Miller novel.)

Bowden is revealed as the defence lawyer who failed to get Cady off his charges by means of a technicality (because he felt his client to be so evil as to be indefensible), and proceeded to undermine his chances in court. If the lawyer is not quite as straight as he ought to be, other American institutions are revealed as equally fragile.

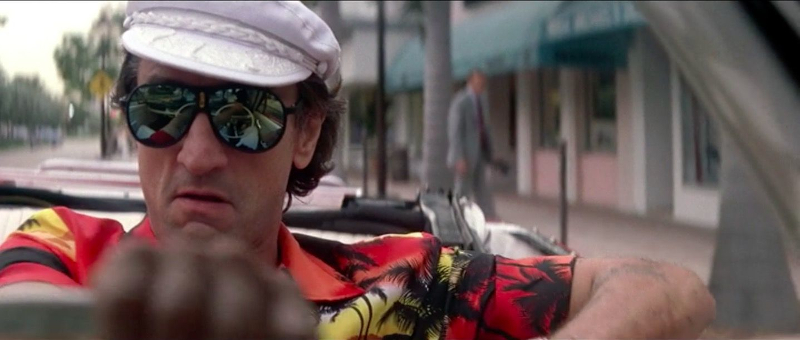

Cady laughs loudly and annoyingly from his seat directly in front of that occupied by the Bowdens’ at the movies; a firework display provides the backdrop for Cady to loiter cheerfully on the Bowdens’ garden wall, and he overtly eyes up Bowden’s wife (Jessica Lange) as the family attend a parade.

Although the American nuclear family is the biggest target of all, father, mother and daughter eventually emerge from the muddy waters at the film’s finale to demonstrate the ability of that institution to survive the onslaught. Nevertheless, it’s not the Bowdens but De Niro’s malevolent Cady who makes the film: like all the best movie monsters, he is a terrifying apparition we feel a compulsion to watch. The Christian religious references in which he deals serve to heighten the unsettling nature of that apparition.

This review was originally published in Strait – the Greenbelt Newspaper, March 1992.

Trailer: