Director – Andrew Levitas – 2020 – US – Cert. 15 – 114m

****

A dramatisation of celebrated photographer W. Eugene Smith’s investigation of Japan’s Minamata environmental atrocity in 1971 – out in cinemas and on digital from Friday, August 13th

This feels like a Hollywood actor-led project with laudable aims which comes unstuck somewhere in the execution. That said, there’s still much to admire.

Minamata is the name of a Japanese coastal town which became synonymous with Mercury poisoning caused by the Chisso chemicals factory in the 1950s and ‘60s.

Following a celebrated career as a war photographer in WW2, W. Eugene Smith photographed the series Country Doctor for Life magazine, now recognised as a landmark in the medium of the photo-essay. In the early 1970s, he and his Japanese-American wife Aileen were introduced to the town of Minamata and its dark secret, and collaborated on a photographic book about it. When we meet him in 1971, played by Johnny Depp (from such films as Charlie And The Chocolate Factory, 2005; Sleepy Hollow, 1999; Edward Scissorhands, 1990, all Tim Burton) he has his own darkroom in a New York loft and has clearly seen better days as he is constantly on the whisky and amphetamines.

Smith receives a visit from Japanese-American woman Aileen (Minami from Tezuka’s Barbara, Macoto Tezuka, 2019; Battle Royale, Kinji Fukasaku, 2000) ostensibly to remind him of contractual obligations regarding an endorsement for Fuji Film (a bit of a problem since Fuji is colour and he’s only ever shot black and white) but actually to enlist his help in exposing the Minamata story. She leaves him a package of cuttings. (Historically this is inaccurate, since the couple were already together and visiting Tokyo when a Minamata movement member contacted them).

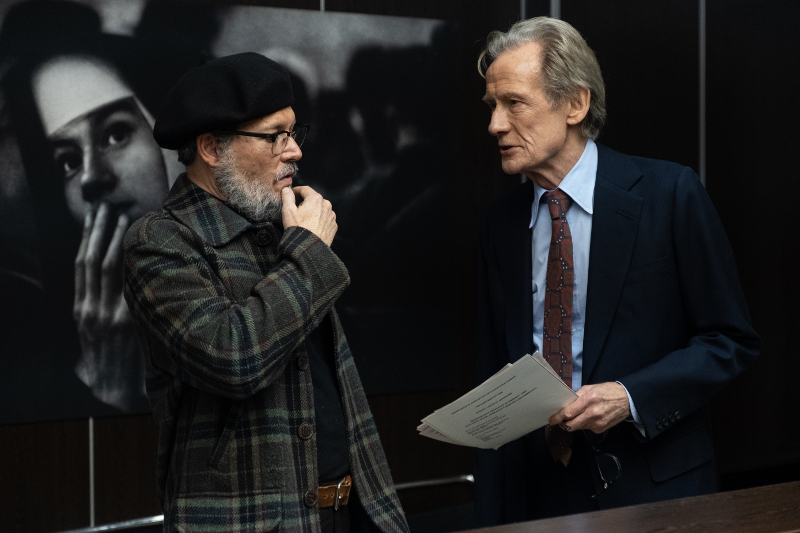

Reading the cuttings in the night, the story starts to get to him, so Smith pitches Life magazine editor Robert Hayes (Bill Nighy). While Hayes holds Smith’s work in high regard, he’s acutely aware of the photographer’s self-sabotaging in recent years and wary of working with him again. Nevertheless, with Life’s backing, Eugene and Aileen head to Minamata where they encounter activists seeking the truth, victims unwilling to place themselves in the public spotlight and Chisso employees determined to halt Smith’s investigation any way they can.

Depp produced the film through his own production company having been interested in Smith for years. He is clearly fascinated by this man battling his own internal demons even as he is held in high regard for his past work. The problem is, there are two separate stories here and instead of merging into one, they compete with each other. Perhaps that was true of Smith’s real life too – he had two marriages (Aileen was his second wife who left him after their work in Minamata) and abused alcohol and drugs throughout his life. Or perhaps Depp the actor is indulging himself by focusing on Smith’s internal demons a little too closely.

Smith at one point gives his camera away to a Minamata local clearly interested in photography causing Aileen to have a whip round in which the locals donate any photographic equipment they can find (including the camera Smith gave away). Aileen appears much more together than her husband and Minami, in her first English-speaking role, shines throughout.

The portrayal of Smith’s encounters with the people of Minamata, sympathetic or hostile, is more effective. Tatsuo Matsumara (Tadanobu Asano from Harmonium, Koji Fukada, 2016; Journey To The Shore, Kiyoshi Kurosawa, 2015; Ichi The Killer, Takeshi Miike, 2001) is a reticent company employee whose daughter has been paralysed by Minamata disease. To him, talking about it with a Westerner is one thing, but going public is quite another. His wife Masako Matsamura (Akiko Iwase from Earthquake Bird, Wash Westmoreland, 2019) eventually agrees to being photographed with her daughter, an image which was to form the centrepiece of Smith’s 1974 Minamata exhibition and prove instrumental in getting the story out into the wider world.

Hiroyuki Sanada (from Avengers: Endgame, Anthony Russo, Joe Russo, 2019; The Railway Man, Jonathan Teplitzky, 2013; The Last Samurai, Edward Zwick, 2003) is on hand as the activists’ leader Mitsuo Yamazaki who heads up protests against Chisso. However, we get closer to Bolex camera-wielding activist Kiyoshi (Ryo Kase from To The Ends Of The Earth, Kiyoshi Kurosawa,2019; Silence, Martin Scorsese, 2016). Kiyoshi has difficulties using his hands as a direct result of the disease, but somehow manages to retain control of them when he uses the camera.

Dwarfing all these roles, though, is Jun Kunimura from ManHunt, John Woo, 1017; The Wailing, Na Hong-jin, 2016; Like Father, Like Son, Hirakazu Kore’eda, 2013) as Chisso boss Junichi Nojima, a man who clearly knows he and his company is in the wrong but is determined to keep the story under warps as long as he possibly can. He alternates in his attitude to Smith between friendly and distant, depending on whether he thinks he can get smith to co-operate with him or not.

In what is arguably the finest scene here (even if it constitutes dramatic invention rather than a matter of historical record), Nojima takes Smith up to the highest walkway in the chemicals plant and offers him an envelope of money if only he’ll surrounded this photographs and walk away from the whole thing. Naturally, Smith refuses in no uncertain terms. The scene plays out like a parody of the Devil tempting Jesus in the gospels of Matthew and Luke. Later, the smarmy Nojima puts on an ingratiating show of public contrition when it becomes apparent he’ll have to pay full compensation to the villagers affected.

The whole thing is bookended by Masako Matsamura holding her paralysed daughter in her arms over a traditional Japanese bathtub, although you see so ittle at the start that you’ve no idea what this is about – only at the end does it make sense. The resultant Smith photograph Tomoko Uemura In Her Bathwas to form the centre piece of his 1974 Minamata exhibition and prove instrumental in getting the story out into the wider world, so it’s a good place to start and end. The photograph itself was withdrawn from circulation by her father who felt that her death in 1977 would be better honoured by his doing so twenty years on. The photograph is re-staged here, although the press handouts refer to it as Tomoko In Her Bath with the surname omitted, suggesting that the film makers may not have had the family’s blessing in doing this.

Nevertheless, it’s not hard to see the attraction of this celebrated photographer for an actor such as Depp, even though Smith’s deep psychological problems made him almost impossible to deal with in real life. Director Levitas seems to be in sync with both his subjects – the photographer and the Minamata cause – and mostly does a good job of keeping the actor’s tendency to overindulge his character in check. Which means that this manages to present a helpful and largely accurate picture of an appalling, specific historical corporate injustice, so it’s good that it’s finally getting a UK release. That said, as recent films about corporate environmental abuse go, I found Samjin Company English Class (Lee Jong-pil, 2020) far more effective.

Minamata is out in cinemas and on digital in the UK from Friday, August 13th.

This page helpfully outlines differences between historical fact and the story as told in the film.

Trailer: