Director – Edgar Wright – 2021 – UK – Cert. 15 – 140m

****

The rollercoaster career of musical duo Sparks with its successful hits and intermittent lapses into obscurity – out in cinemas on Thursday, July 29th

There’s a story about John Lennon phoning Ringo Starr to say, “you won’t believe what’s on television – Marc Bolan doing a song with Adolf Hitler.” This was Sparks’ auspicious debut on BBC music show Top Of The Pops in the early 1970s playing what is probably their best known track, This Town Ain’t Big Enough For The Both Of Us, a broadcast estimated to have reached some 15 million people. Everyone was talking about this the day after – that’s mentioned here, and it’s something I myself remember from my own school days: the lively energetic singer (Russell Mael) and the suited, almost motionless, keyboard player (Ron Mael) with the slicked back hair and the Hitler moustache. The Hitler appearance may not have been deliberate, but that image of the duo – the extrovert and the introvert – has become the band’s enduring media image over the years.

One gets the impression from passing moments in this film that Charlie Chaplin was an equally formative presence for Ron – and though it’s never mentioned, Chaplin made the film The Great Dictator (1940) in which he played a Hitler type despot as well as a Jewish barber unfortunate enough to look like him…but I digress. Although it’s clear that both brothers loved movies.

They were born and raised in California where their dad used to take them to movies – Westerns, Adventure, Science Fiction – until his unexpected death when Ron was 11 and Russell 8 after which the two boys looked out for their mother. Both parents get a dedication at the end, where the credits also provide a tantalising series of stills as well as a list of the brothers telling us a series of fantastical facts about themselves, many of which are obviously apocryphal. This comes from some 12 hours of interview footage conducted by Wright, in which both he and they clearly had a good time.

Wright has also secured footage of other interview subjects, among them producers (Todd Rundgren, Giorgio Moroder, Muff Winwood, Tony Visconti, James Lowe), Sparks musicians (Christi Haydon, Dean Menta, Harley Feinstein, David Kendrick, Earle Mankey, Leslie Bohem, The Go-Go’s’ Jane Wiedlin), other musicians (Erasure’s Vince Clarke, Franz Ferdinand’s Alex Kapranos, all too brief snatches of ‘Weird Al’ Yancovic and, in audio only, Björk) and fans, including the woman who hugged one of them onstage in a show and immediately realised it was a bad idea.

The documentary charts the highs and lows of a musical career to date covering all 25 albums in chronological order. Wright is clearly an admirer – you’d need to be to make a decent film about Sparks and not sell their music or personae short – and after the journey of making this film is probably also a friend because as his camera records both the brothers and their numerous collaborators and admirers, there’s an undeniable warmth for the duo from all concerned.

After forming a number of bands, the two brothers eventually coalesced into HalfNelson, recording an album for Todd Rundgren’s Bearsville Records which failed to sell. The record company suggested the new name of The Sparks Brothers, which the duo managed to shorten to the punchier Sparks for a second album, which also failed to sell.

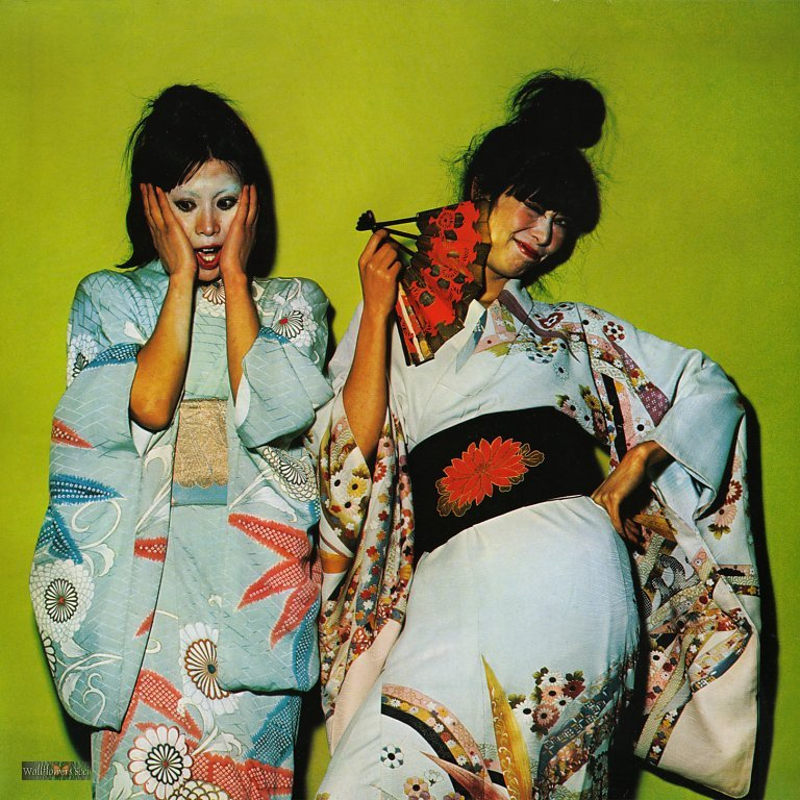

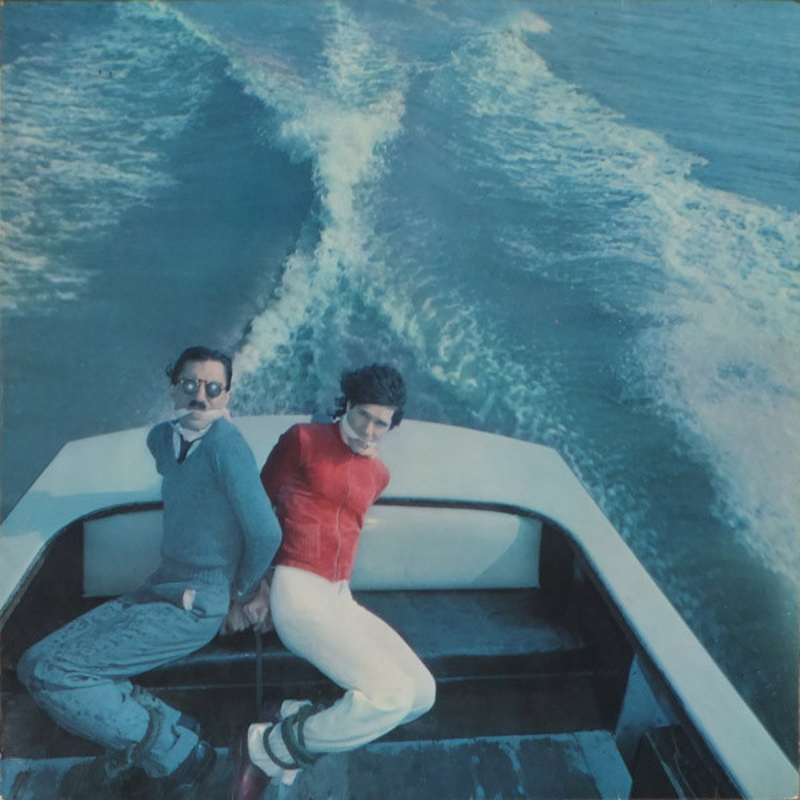

At any one point in their career there always seems to have been one person who ‘got’ what they were doing when others didn’t. When they decided they might be better off in Britain, which had a history of producing quirkier music acts than the US, they found a contact at Island records which resulted in a deal, their biggest selling single This Town… and three successful if distinctly odd albums Kimono My House, Propaganda and Indiscreet. The first two had iconic sleeves – the two geishas with smeared make up for KMH, the brothers tied up in a speedboat for Propaganda with a reinterpretation of that sleeve by Edgar Wright summoning the remark from a Mael, “that’s why you’re a film director and I’m not.” Not wanting to repeat themselves or get stuck in a rut, they completely changed their sound for the third album with the result that it sold less well to their fan base and Island dropped them.

Other career highlights include a blunder when they told a journalist they were going to work with Giorgio Moroder to which she replied, “I talked to him, and he didn’t mention it to me.” She was however generous enough to put them in touch, resulting in rather more electronically based songs including the successful The Number One Song In Heaven. Later, they collaborated with much younger band Franz Ferdinand for the album and band FFS. Sparks have had different hits in different countries over the years such as the UK, the US, Germany and France.

As the rest of their career / discography is traversed, you hear Sparks songs that you didn’t realise you knew. (At least, that was this writer’s experience.) Many musical acts are successful for a few years and then trade of that for the rest of their lives. Sparks are not one of those, preferring to constantly move forward and break new ground. As if to wilfully contradict this, in 2008 they played 21 gigs in London performing all their albums to date, one each night. At once looking back and pulling off a near-impossible feat.

Joseph Wallace and team who did Sparks’ stop-frame music video Edith Piaf (Said It Better Than Me) (2017) throw in some visually arresting animation of various different types (stop-frame, cut-out, 2D CG) which fit the subject perfectly. Elsewhere, movie clips include the spaceship from This Island Earth (Joseph Newman, 1955) and the allosaurus from One Million Years B.C. (VFX by Ray Harryhausen, 1966), there’s talk of a failed movie project with Jacques Tati and even a shot of Jean-Luc Godard. Sparks’ numerous TV and filmed appearances over the years means there’s a considerable quantity of material of them performing, all good stuff, as well as gems like Paul McCartney‘s Coming Up video in which he impersonates Ron Mael on keyboards as well as numerous other musicians.

After about the fifteenth album it all starts to get a little wearing. Overall it could benefit from a little more analysis of why the music / songs is / are as rich as they are and perhaps even some detractors because, as evidenced by their less popular periods, Sparks have not consistently been successful at reaching audiences (even if they deserve to do so). If we could understand why parts of their career didn’t really work, we might more readily understand why the good bits are as good as they are.

Alongside with clips of their appearance in weak disaster movie Rollercoaster (James Goldstone, 1977) there is no more than a mention that they scored a film for legendary Hong Kong director Tsui Hark in Knock Off (1998) and the production’s timing is such that it can’t say much about the upcoming musical they wrote Annette (Leos Carax, 2021). But there’s quite a bit about their 1990s musical adaptation of manga Mai, The Psychic Girl for director Tim Burton before that project fell apart, augmented by animated pages of a manga showing the two brothers falling into oblivion.

Nevertheless, despite its faults this is a great introduction to a band less well-known than they ought to be, packed with great interview and archive material plus some surprising insights both from the duo themselves and also people who’ve worked with or admired them over the years. In addition to being worth seeing as a movie in its own right, it also possesses great interactive potential for Blu-ray, DVD or website. It would be nice to be able to access parts of the film or any additional material that didn’t make the edit by specific album or theme (family background, the brothers’ love of music, their love of movies, different hits in different countries). For now, though, the opportunity to view this useful documentary in cinemas will do just fine.

The Sparks Brothers is out in cinemas in the UK on Thursday, July 29th.

Trailer: