Director – Kevin Macdonald – 2021 – UK – Cert. 15 – 129m

****

A pro bono lawyer defends a post-9/11 terrorist suspect in Guantánamo Bay against his US Army prosecutor – plays Curzon Home Cinema rental from Monday, October 4th

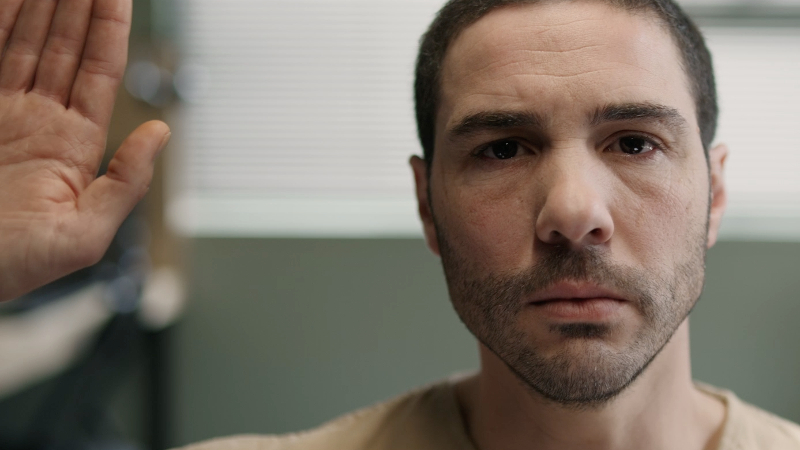

Based on a true story, this kicks off in Mauritania, North West Africa in November 2001 – as a title tells us, two months after 9/11. Mohamedou Ould Slahi (Tahar Rahim) walks on a beach then attends a Muslim wedding in Mauritania, to which he’s returned after living in abroad in Germany. During the celebrations, two local cops turn up and want him to come for questioning about his brother, whose current whereabouts he reminds them he doesn’t know. “The Americans are going crazy since the attacks two months ago,” they tell him. Momentarily alone, changing out of celebratory robes into something more casual, he erases his mobile phone contacts before agreeing to go with them.

Three years later, New Mexico law firm partner Nancy Hollander (Jodie Foster) learns of his disappearance and that the story has just broken in Der Spiegel that Slahi is currently allegedly being detained in Guantánamo Bay as “one of the organisers of 9/11”. The US government has recently stated that inmates have the right of ‘habeas corpus’ – if the evidence against them isn’t deemed sufficient to hold them in detention, they should be released. Hollander’s junior colleague Teri Duncan (Shailene Woodley) speaks French so is co-opted onto her team as translator.

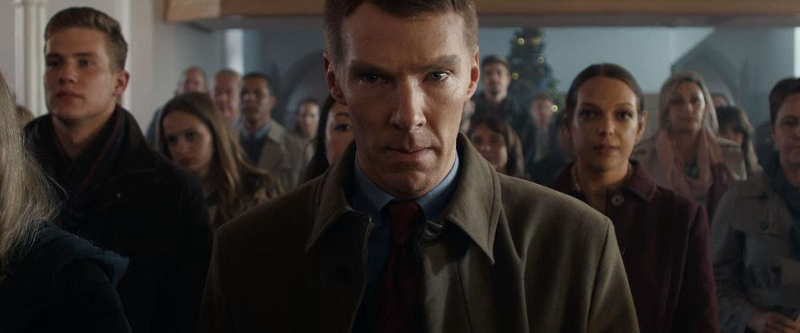

Meanwhile, the US army put military lawyer Stu Couch (Benedict Cumberbatch) – who knew one of the pilots on the 9/11 South Tower plane – on the prosecution for the Slahi case, seen by the Administration as the first Death Penalty case to clear the backlog.

What follows juggles these three plot-lines – the prisoner, the prosecution lawyer, the defence lawyers. The film is based on the account of Slahi himself, later published (redacted) in book form while he was still in prison and proudly shown off by the real life Slahi in numerous, international, published versions in different languages as the end credits roll.

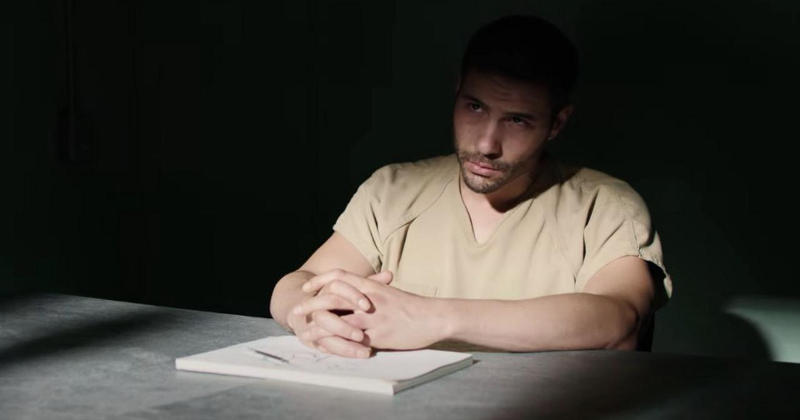

With no help from the US government, Macdonald’s team have reimagined the Guantánamo facility for the screen, with South Africa doubling for Cuba during shooting and the real life Slahi on board as a consultant. The cell in which he spends his time is a dismal affair, the handcuffing of the wrists every time the door is opened to let him in or out complex and dehumanising protocols. When outside for exercise, he’s surrounded by four canvas walls and never meets another soul (although he bonds with the unseen next door prisoner by talking through the walls, known by his prisoner number 241 and his town Marseilles).

Only when at one and a half hours into the narrative he’s finally handed over by his regular interviewers to the more ruthless Military Intelligence interrogators is Mohamedou subjected to the truly horrific tortures for which Guantánamo is infamous – uncomfortable forced standing positions for hours at a time, continuous exposure to heavy metal music, being beaten up by masked assailants. Such US military prisoner abuses have arguably been portrayed more effectively elsewhere in films, even if their Guantánamo context has not.

Macdonald is more interested in the longer term abuse of Slahi’s confinement than in the minutiae of horrors to which the inmate was subjected over this short period. And he seems fascinated by the religious angle: how Mohamedou’s Muslim faith sustains him and allows him to come out of the whole experience not bearing a grudge. Indeed, he tells the judge trying his case via videolink that in Arabic, the words for forgiveness and freedom are one and the same: only by forgiving can he be truly free.

Surprisingly perhaps, the director is at least as interested in the lawyers trying and defending him as in the defendant himself. Perhaps this is inherent in Slahi’s book. As with the Slahi narrative, that for Couch places much emphasis on religion, with Couch a churchgoer possessed of a Christian faith which compels him to seek for justice. Initially, this means prosecuting a terrorist, but as he digs deeper and deeper and discovers the military’s case against Slahi to have been produced under duress, he finds he can no longer prosecute with a clear conscience.

On the defence side, while Hollander appears not to be aligned with any orthodox religion, she has a clear belief in law and due process as a medium for truth and justice, an ideal Mohammedou shares. She throws assistant Duncan off the team when the latter becomes convinced Mohammedou did what the prosecution claimed. “You’ve got to believe in your own shit,” she admonishes her junior.

The Mauritanian plays Curzon Home Cinema rental from Monday, October 4th.

This review was originally written for the film’s Glasgow Film Festival screening.

Trailer:

2021

Curzon Home Cinema rental – Monday, October 4th

Amazon Prime – Thursday, April 1st

Festivals:

2021

Friday, Thursday, February 25th to Sunday, February 28th.