R.I.P. Gene Hackman (1930-2025)

Director – Francis Ford Coppola – 1974 – US – Cert. 12a – 113m

*****

A surveillance expert records a conversation between two people, then worries about turning the recording over to his corporate client as contracted – 50th anniversary 4K Restoration is out on UHD, Blu-ray and DVD on Monday, July 15th, 2024

There’s nothing else quite like The Conversation in cinema.

Union Square, San Francisco. People milling around. Among them, a couple (Frederic Forrest and Cindy Williams) having a conversation. Also in the square, a man in a plastic mac (Gene Hackman). And another man (Michael Higgins) following them around, holding a bag. And, at two separate windows above the square, two long range microphones.

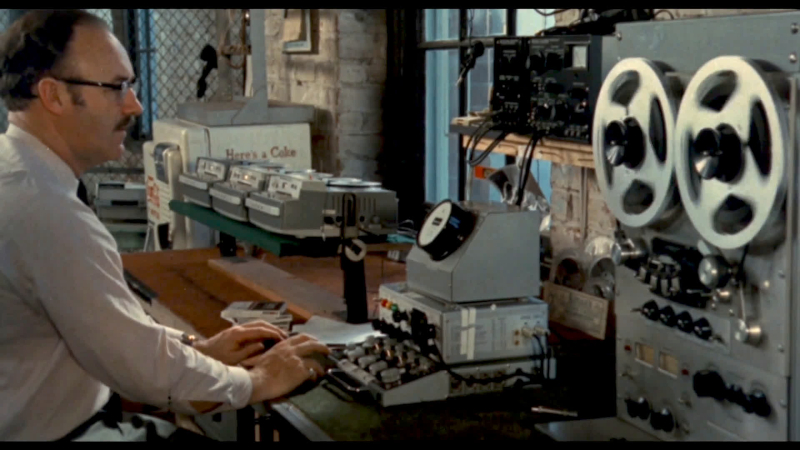

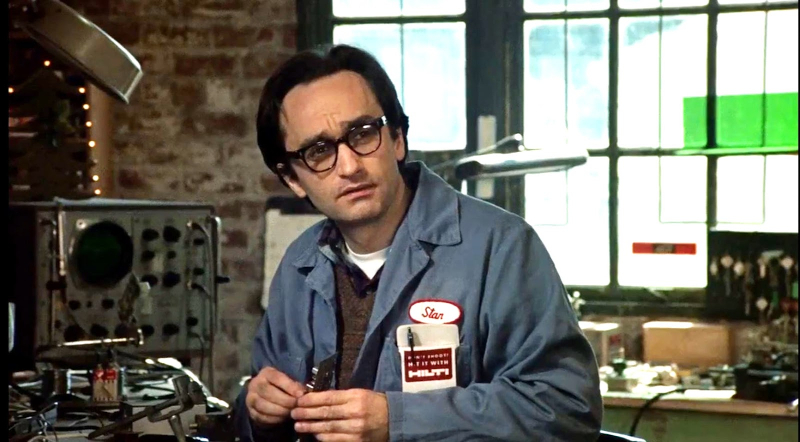

The first man, Harry, enters a nearby van, inside which is his recording assistant Stan (John Cazale). He’s shortly followed by the other man, Paul, who believes the couple spotted him trailing them.

Harry pays a nighttime visit to his girlfriend Amy (Teri Garr). She wants him to spill his secrets. He claims he has none. He leaves, with her telling him not to bother to come back.

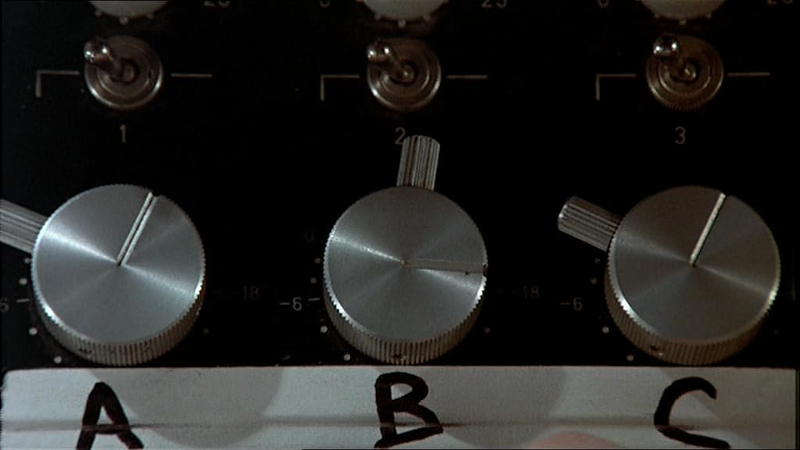

He goes to work in his office, situated at one end of the floor in an otherwise deserted warehouse. He lines up the three spools of recording tape, A, B, and C, playing them back in sync through a device which allows him to increase or decrease the volume of each sound source. He wants to prepare the clearest, most accurate recording he can to deliver to his client. He fiddles around with the mix.

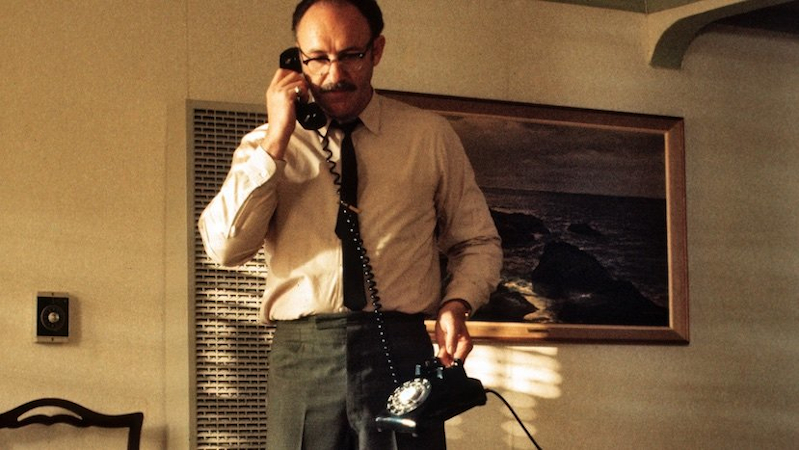

He phones his client from a payphone (he has no listed phone number in his apartment) and arranges a meeting at 2.30 the next day when he can hand the tapes over to his clients personally. But when he goes there, he instead meets the director’s assistant Martin Stett (Harrison Ford), argues with him, and refuses to hand over the tapes.

He visits a surveillance industry convention, where he and William P. Moran (Allen Garfield) are the two celebrity, guest attendees. He does not hold this “Bernie” Moran in high regard. Bernie, by way of contrast, will later describe him as “the best bugger on the West Coast.” Harry is somewhat shocked to find Stan working for Moran. Somehow, Moran, Stan, Paul and Harry, along with a couple of women, find their way back to Harry’s warehouse premises to party. Harry finds himself talking with one of the women, coaxed into pouring his heart out, and telling her about his failed relationship.

He becomes increasingly concerned about the content of the tapes, checking himself in the nearest room he can find to the hotel room 774 mentioned by the talking couple. In the adjoining 773, he sets up surveillance devices to listen in, but what happens next is something he hasn’t bargained for.

The above synopsis leaves out a few surprises that you definitely won’t want revealed if it’s your first time seeing the film. That said, it’s a film to return to again and again, and this writer has seen it countless times since first encountering it in the 1980s. There is much about it that is extraordinary. I can’t claim to have seen everything Coppola has ever made, but I’ve seen a large portion of his films and to date it remains my favourite of his works.

It’s a little independent movie made by writer-director Coppola between two big Studio pictures, The Godfather (1972) and The Godfather Part II (1974). It doesn’t have the multiplicity of characters that those movies have, and consequently allows the space for a detailed character study. It is helped no end by the spectacularly good casting of its leading performer.

Hackman’s Harry Caul is a remarkable piece of acting, portraying a man at the top of his professional game, which has dehumanised him to the point where he can barely relate to others. He is furious at the discovery that his landlady has an extra key to his apartment, which comes to light when he finds she has come in and left him a present, his attitude turning her goodwill gesture into an unwarranted invasion of his personal privacy. He alienates both girlfriend Amy and trusted assistant Stan by being too protective of or overly obsessed with his work.

His only solace is his saxophone, played along to jazz records in his apartment. At the end of the film, when everything has fallen apart, and he has ripped his flat apart in search of the bug he is convinced has been planted there, his sax is all he has left. He sits amidst the wreckage, playing it.

The role is Hackman’s favourite piece of work, an assessment with which it’s hard to disagree. Cazale brings out the insecure Stan’s constant desire for validation by others, the reason he leaves Harry for rival Moran. Garfield plays extrovert much as Hackman plays introvert. He has something of the crook about him. An exhibitor at the convention claims to Harry that Moran ripped off his latest device, and spending time in Garfield’s presence, you can easily believe it.

Forrest and Williams as the couple, though they do appear later individually, not to mention in a dream sequence of Harry’s, are primarily there as the two people whose conversation is recorded at the beginning. Both do what’s required of them, but it’s hard to see how actors could have done much more with these particular roles.

The big surprise in the cast is the then largely unknown Harrison Ford as the director’s assistant. He has an undeniable presence about him, even or perhaps especially when he’s not saying anything, projecting a profound sense of menace. He clearly has what it takes to become a huge star.

The two women with whom Harry attempts to connect – the fading girlfriend and the whore who takes him in to her confidence – seem dated as characters viewed through 2024 eyes. This all takes place in a man’s world. These women are all defined by their interaction with men (aside, arguably, from the woman in the couple about whom we know very little.) Much has changed in 50 years: today, Harry would have a mixed team of men and women following the couple in Union Square. (Or would he?) Perhaps his number two would be a woman. Perhaps he himself would be.

One of the most remarkable aspects of the film is its use of sound.

In the opening sequence, in the recording of the couple, some of what they say can be heard and understood and some of it cannot. Harry’s associates comment on their recordings – “25%”, “40%”.

As the film’s sound designer and (in his first credit as such) picture editor, Walter Murch, in a Q&A following a screening of the 4K Restoration at London’s BFI Southbank, mentioned how in analogue sound recording (which was what it was in 1974), when a microphone fails to properly pick up a sound, e.g. because it’s too far away, the sound simply goes quieter or disappears.

In The Conversation, where the couple’s words aren’t picked up, they distort and (my words here) their sound goes all funny and bubbly. As Murch pointed out, that’s what happens in digital recording, so in a sense the film imagined that phenomenon before it came to pass in the real world.

In terms of drama, it creates the sense that you’re not quite hearing all the detail in a way that, if the sounds were simply lower or absent, you wouldn’t. It’s an observation that, as soon as someone says it, seems obvious; but before they do, it’s not something that occurs to you.

Murch got his first Sound Designer credit – the first in the film industry – on an earlier, independent Coppola picture, The Rain People (1969) because Coppola wanted to find an appropriate way of acknowledging Murch’s contribution to the film.

The Conversation benefits further from a remarkable, mostly piano-only score by David Shire, which emphasises the loneliness of Harry Caul’s self-isolated, solitary lifestyle. At times, such as a scene when Harry inadvertently finds himself in a crowded corporation building lift with the woman he has recorded, Murch takes the sound and distorts it to heighten the effect of alienation. Given that the subject of the film is, arguably, sound, our perception of what we hear, and how it’s meaning can change with tweaks in the audio quality, this seems peculiarly appropriate.

Although it’s heavily stylized, fifty years on, the film has held up remarkably well. Although it fortuitously came out around the same time as Watergate, and with the passing of time the immediacy of that historic connection has vanished, these days, here in the UK at least, we are increasingly subject to a surveillance society, with cameras placed on numerous urban streets.

Thus, those questions regarding the dangers of surveillance – what difference does it make to society?, who is in charge of it?, what effect does the job have on those people that do it? – remain as pertinent as ever.

The Conversation is out in the UK in a 50th anniversary 4K Restoration on UHD, Blu-ray and DVD on Monday, July 15th, 2024.

Trailer: