Director – Brett Morgen – 2022 – US – Cert. 15 – 135m

*****

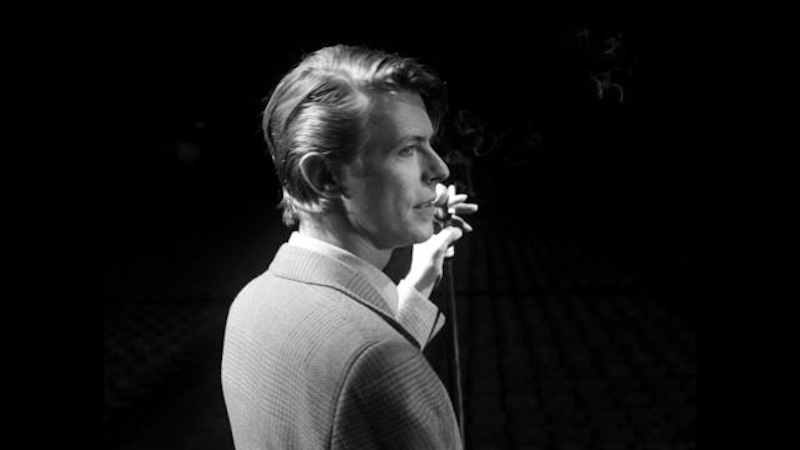

David Bowie explored through his own words, accompanied by images of his life and art, many of his songs and extracts from numerous live performances – out in IMAX in the UK on Friday, September 16th and wide in cinemas on Friday, September 23rd.

In 2018, seasoned writer-director-editor Brett Morgen (Jane, 2017; Kurt Cobain: Montage Of Heck, 2015; The Kid Stays In The Picture, 2002) was granted unprecedented access to David Bowie’s personal archives and four years later we have the first film to be supported by the Bowie estate. Knowing all this, you enter the cinema wondering exactly what you’re going to get.

You’re immediately confronted by a quote about Nietzsche and God which is then revealed as a quote from Bowie 2002, the film immediately putting Bowie on a par with one of the nineteenth century’s greatest philosophers and arguably even God. The subject of Nietsche doesn’t come back up, but God does, quite a bit, with Bowie’s religious-leaning song “Word On A Wing” putting in an appearance and David’s voice-over talking about “something…a force directing the universe”. Like many of us today, he struggles with the word ‘God’ – is it the right word? Is there a better or more appropriate one if you believe in some sort of higher power – but he clearly has a belief in something behind it all.

There’s a lot of Bowie talking in here… it’s never really explained in the film (or in the perfunctory press handouts), but perhaps this material is culled from TV or radio interviews over the years, or else Bowie may have done a considerable amount of voice recording just putting down his thoughts on issues large and small over time, like a sort of ongoing audio blog, something we should perhaps all do if only for our descendants. Morgen draws helpful threads out of all this. Bowie is highly aware that life is something at which we all only get one shot (so that rules out ideas of reincarnation) and wants / wanted to do the best with it he possibly can / could. (You listen to him speak, but the recordings are in the past, of someone who has since passed on, so which tense to use is an issue.)

Bowie is clearly fascinated by both the way human beings adorn their bodies with clothing and make-up and by the world around him. He lives / lived in a nomadic state, refusing to buy a house and moving around the globe, something you can see from his career – Brixton-born, a hopeless then rising British career in the sixties and early seventies, a brief US career in the mid-seventies, time in Berlin in the late seventies, embracing the US mainstream in the early eighties.

The film doesn’t really guide you through all this, in the way that the V&A’s groundbreaking David Bowie Is exhibition did in 2013, rather it assumes you know the chronology and discography – or if you don’t, that you’ll just go with the flow. And where that exhibition covered the early life and work of the struggling, pre-success David Bowie pre-Ziggy Stardust and all periods since, even if it put rather less emphasis on everything after 1983’s Let’s Dance, in terms of the footage and music used this film focuses on the British Ziggy Stardust / Aladdin Sane period, the Berlin period and the embrace of the US mainstream with Let’s Dance and subsequent tours.

The song “Hello Spaceboy” turns up from later album Earthling (1997), his acclaimed The Next Day (2013) is absent altogether and Blackstar (2016) is briefly represented by excerpts from the video of its title track.

There is however much archive footage from Bowie’s later years, for instance of him working on art or performing Lazarus, not to mention film clips (Absolute Beginners, Julien Temple, 1986; Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, Nagisa Oshima, 1983; The Man Who Fell To Earth, Nicolas Roeg, 1976; and more) and extraordinary footage of Bowie playing The Elephant Man on Broadway. He’s also seen wandering around hotel corridors and lobbies, checking in at airport desk queues, and in the Far East, on a high-tech escalator (some of the footage shot using mirrors so that it resembles something out of M.C. Escher) or past night-life food and girls street vendors in Thailand.

There is also a huge quantity of concert footage, including a lot of footage of male and female teenage British fans from the Ziggy years, and thanks in no small part to the involvement of long time Bowie collaborator Tony Visconti, the edit often moves seamlessly between different recorded studio (sound, sometimes with promotional video accompaniment) and live performance (sound and video synchronised) versions of a particular song, so it’s something far more cinematic and time transient than just hearing a familiar recorded song, seeing a single live performance or watching a video (as exciting and valid as all those different media options might be).

After an initial five or ten minutes where you’re wondering if you’re going to see much footage of Bowie himself – it all seems to be special effects stars and planets as he talks about meaning or the universe – it kicks into a lengthy section (forty minutes?) based almost exclusively around Bowie touring Ziggy Stardust before skirting his first foray in the US to explore the Berlin period (“A New Career And A New Town”, “Sound And Vision”, “Heroes”, “DJ” and a lot of the Low / Heroes ambient / instrumental tracks).

Bowie admits that his Let’s Dance album was an attempt to play to the idea of what a mainstream rock star should look like, with attendant parameters, and to finding this creatively frustrating (the album was a huge seller back in the day, a blockbuster LP album in the music world in much the same way that movies like Star Wars (George Lucas, 1977) had previously created the blockbuster movie phenomenon in the cinema world.

Personally I’ve always found that record unsatisfying, and his analysis here accurately explains why, although the live footage (like all the other live footage used in this film) remains exhilarating and a demonstration of what an incredible live performer David Bowie, in his different periods and different guises, was (and, I guess, if you’re watching footage of him today, still is).

There’s a moment maybe forty minutes before the end where the film feels like it’s going to finish indeed goes to a black screen, but then it starts up again and carries on. Which is fine, except that Morgen doesn’t seem to know how to end his film, and when the end does finally come, it feels somewhat arbitrary.

That said, although the piece runs well over two hours, it’s enthralling and compelling stuff, a journey into the mind of a great artist and arguably the greatest media practitioner of the twentieth century.

Bowie continues to confound, and although the film is available in IMAX – in which viewing format I would recommend you see it – it was sadly only press screened in a regular (albeit a very nice West End) cinema, suggesting that perhaps its distributors don’t really understand it. Well, in the 1960s, no-one really understood the struggling, largely unknown, David Bowie. However, if you connect with his personality, life, music or work on whatever level, you’ll probably understand it rather better. Highly recommended.

Moonage Daydream is out in IMAX in the UK on Friday, September 16th and wide in cinemas on Friday, September 23rd.

Trailer: