Directors – Jane Harris, Jimmy Edmonds – 2021 – UK – 60m

****

People talk about their experiences of bereavement in the light of the COVID-19 lockdown – now free to watch (donation suggested)

In March 2020, the unthinkable happened as the world entered a global pandemic. In the ensuing year or so many people lost their lives while many more felt and indeed still feel a sense of loss for the ’normal’ life that existed beforehand. Directors Harris and Edmonds are no strangers to bereavement having lost their son unexpectedly at age 22 while he was travelling abroad in 2013 and part of their process of dealing with it was to make the excellent documentary A Love That Never Dies (Jane Harris, Jimmy Edmonds, 2018) in which bereaved parents talk about their different experiences of losing children.

Not everyone has suffered the misfortune of losing a child, but if you’re reading this you will invariably have lived through the COVID-19 pandemic, at least thus far. This latter condition is universal. So, what does the experience of bereavement have to say to our current situation of the pandemic – or, for that matter, what does our current situation of the pandemic have to say to our experience of bereavement?

A welcome companion piece to the earlier film, this new one works equally well as a stand-alone entry – it doesn’t matter if you’ve seen the earlier film and (aside from the introductory five minutes) there’s very little repeat material. It follows a similar format with Harris acting as our guide and questioning a number of health professionals and / or bereaved people about their experience both of bereavement itself and of pandemic lockdown – and the complex relationship between the two.

The title refers most obviously to the face masks that have been mandatory for shopping, travelling and other activities outside the home in the UK. Just as we have tool kits for surviving the pandemic – face mask, bottle of hand sanitiser – so we have tool kits for coping with grief. As the wife of a couple who lost their child pre-pandemic points out, grief itself is worn like a mask – you put it on when you leave the house and remove it when you come back in.

Another interviewee talks about losing her husband and experiencing her own life grinding to a halt, then later seeing the life of the wider world around her stopping in a similar fashion when the pandemic hit. As Harris comments elsewhere, suddenly death was on the agenda and nobody was immune.

Alex, a nurse who lost her husband Tony to bladder cancer, talks about the uncertainty of life living and caring for a person with a potentially fatal illness versus the certainty once that person has died, comparing the uncertain phase to many people’s experience of life under pandemic conditions where anyone might contract then be killed by the virus at any time. She feels good, she says, that her husband is not here during COVID.

Dr. Kathryn Mannix, a palliative care specialist of some three decades standing who is yet to experience bereavement herself among immediate family and friends, describes the pandemic as being the closest thing to wartime that many persons currently living have experienced, in terms of the soldiers who went off to war but never returned home.

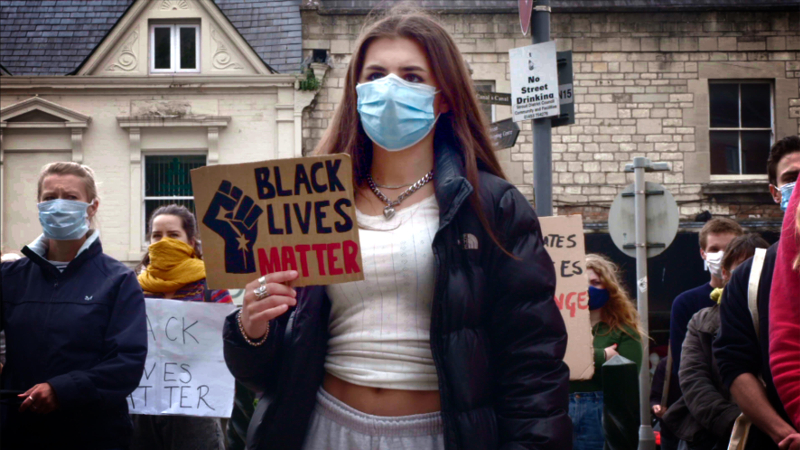

Bereaved parents Deirdre and Liam talk about the value of spending a week with their terminally ill, young daughter before she died in terms of coping with the loss that followed. With all the people who have died of COVID-19 as well of those who have died of other causes under lockdown, there may be a pandemic of grief approaching as vast numbers of people struggle to deal with their losses. On top of this, there’s been a growing awareness of the effects of such factors as race, difference and privilege with the killing by Minneapolis police of George Floyd and the rise of the #blacklivesmatter movement.

Meanwhile in the UK, the NHS issued tablets to potentially dying patients while they were isolated in hospital to enable their loved ones to spend time with them, albeit online. I’d have liked to have heard more about not only the role played by technology in dying and bereavement during the pandemic under various levels of lockdown but also the way the restrictions of these levels have interrupted the formal and less formal rituals of death and bereavement – funerals, gatherings, commemorations and so forth.

We do however get a fascinating account of one highly personal bereavement ritual, a mother who cut off most of her hair years after her young daughter’s death in an attempt to understand the effect on her daughter’s undergoing the shaving of her head for chemotherapy. It’s also noteworthy that a number of people appear not as themselves before the camera but as themselves seen on a screen of a laptop rather than in person, a recurring image which non-verbally articulates something very real about the lockdown experience as distant people yearn to see and touch one another in actual, real physical space rather than merely as a moving image on a screen.

Overall though, like Harris and Edmonds’ previous documentary, this contains much provocative and helpful food for thought. Bereavement under the pandemic is a really important issue that isn’t (yet) being discussed much and it’s a conversation which the UK and the wider world needs to have. Hopefully this film will help kickstart that very necessary process.

Beyond The Mask is now free to watch (donation suggested).

Trailer:

Visit The Good Grief Project website. To set up a screening of the film near you, please contact the film-makers.

2022

From Friday, June 24th: free to watch online.

2021

Stroud Film Festival on Sunday, July 4th, cinema and online.