Director – Ching Siu Tung – 1987 – Hong Kong – Cert. 15 – 95m

*****

Some of the most seminal offerings of the commercial Hong Kong cinema are the product of creative wizard Tsui Hark. The producer who first gave John Woo his niche as bullet strewn action director on A Better Tomorrow (1986) also ensured director Ching Sui Tung’s place in fantasy film’s Hall of Fame with this stunning little offering.

The Hong Kong supernatural, fantasy genre is itself defined almost single-handedly by Tsui’s groundbreaking epic Zu: Warriors From the Magic Mountain (1983). CGS both typifies the genre and proves one of its finest examples. CGS spawned two sequels for what Tsui describes as “sentimental reasons – when the ghost died at the end, we want her to come back pretty badly.” He admits the sequels weren’t as good, though.

CGS opens in a downpour as a rain sodden Leslie Cheung (known to Western audiences from such diverse fare as A Better Tomorrow and art house hit Farewell My Concubine, Chen Kaige, 1993) watches a grim, head lopping argument between two bandits as he does his cowardly best to look inconspicuous. His work as a debt gatherer suffers something of a setback as he discovers the ink in his books has run with the damp, so once he arrives in the nearby town he’s unable to collect the payments he’d expected.

Out of pocket, he finds himself forced to find free lodgings for the night. The locals cheerfully direct him to the local temple in the woods – through which roam (or fly on wires) beautiful young Chinese starlets in flowing dresses cast as ghosts whose sole purpose in unlife is to extract the life essence from unwary passers-by.

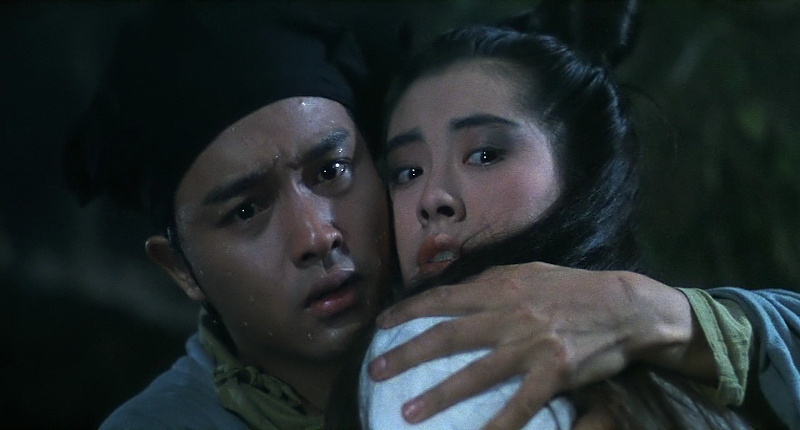

However, one of them (Joey Wong from City Hunter, Wong Jing, 1993), in an unlikely Oriental variant of the Tart With A Heart, is only among their evil ranks because she’s been tricked into it and is really quite a nice girl at heart. Inevitably, Cheung runs into Wong and a romance develops – with boy unaware of girl’s undead identity and girl fighting off her evil sisters and various other evil forces along for the ride.

These local powers of darkness include a tree spirit able to turn at will into either an actor in drag or a giant tongue, a horde of zombies hiding out in the temple basement bought to life by droplets of blood and (for the bravura underworld finale) Wong’s demon bridegroom Lord Black.

Also in the vicinity (in case you don’t think the above is enough to keep events rattling along at a good pace) is sword bashing Taoist priest Wu Ma who not only matches the girls’ flying stunt work with spectacular somersaults but at one point even pulls off a rap version of the classic Tao Te Ching text.

As this latter event indicates, CGS’ tone veers all over the place – but it’s never a problem. It works very well as a pure boy meets girl piece, a theme to which producer Tsui has successfully returned either with supernatural (The Wicked City, Mai Tai Kit, 1994) or historical period (The Lovers, 1995) trappings.

Cheung projects just the right little boy lost quality to make one identify with the naivety of his character; playing opposite him, Joey Wong, who consistently looks both gorgeous and glamourous, is a real winner trapped between the worlds of the living and the dead. Who can forget the affecting sequence where she repeatedly ducks him beneath the surface of water in a barrel to prevent her soul-hungry sisters smelling his essence? Or the scene about halfway through where she struggles to explain to her lover that she is, in fact, dead.

There’s much more to it all than this romance, though. Bags of genre atmosphere as only the Hong Kong Chinese (and possibly fan Sam Raimi) know how combine with breakneck action sequences at which Ching Siu-Tung proves himself a master (as he would again on the likes of period sword and supernatural epic A Terra-Cotta Warrior (1990) and Indiana Jones rip-off Dr. Wai In “The Scripture with No Words”, 1996).

On top of all this, the special effects sequences are nothing less than breathtaking. Take the giant tongue, swirling around in the confines of the temple basement, hurling its full length through acres of forest undergrowth, or disappearing root‑like into the ground while the cloak of the spirit man in drag stands erect around where it stood seconds before.

Or take the final reel, when multiple skulls of tormented souls suddenly fly unexpectedly from Lord Black’s figure towards the hapless heroes. Moments like this demonstrate that Tsui and Ching are very much to the East what Lucas and Spielberg are to the West. Decades on, CGS has lost none of its ability to astound or enthral, and remains as good an introduction to supernatural Hong Kong movies as one could wish.

Review originally published in Starlog UK circa 2000 or 2001 when a new print of the film played London’s National Film Theatre.