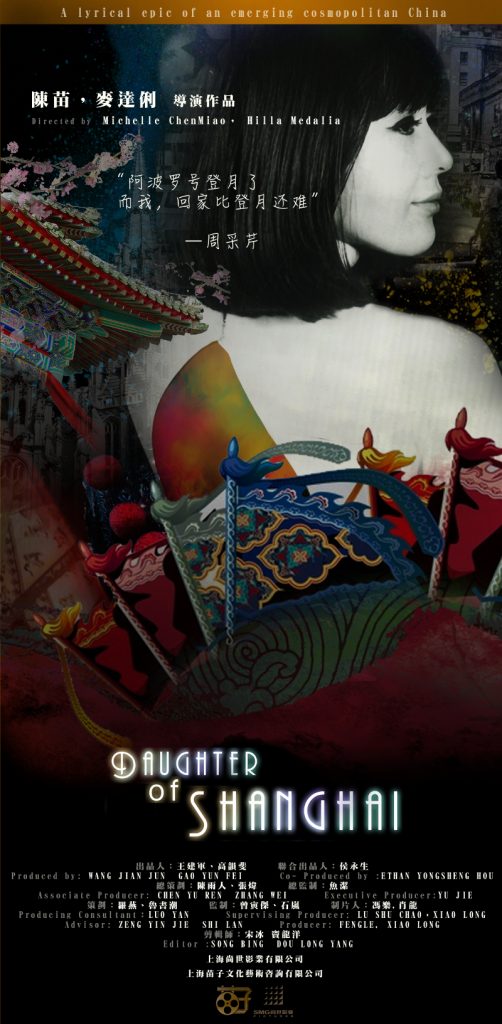

Directors – Michelle Chen Miao, Hilla Medalia – 2019 – China – Cert. N/C 15+ – 90m

****1/2

A chronicle of the life and on-off career of Chinese-born, RADA-trained actress and screen legend Tsai Chin – available to rent online until Wednesday, May 12th in the UK & Ireland in the Chinese Cinema Season 2021 as part of the Approaching Reality documentary strand

“I was born in a trunk when my parents were on tour in Tianjin.” The daughter of legendary Peking Opera star Zhou Xinfang, Tsai Chin came to London towards the end of her seventeenth year when she was the first Chinese person to be accepted at RADA where she found herself alongside the likes of high-born, Welsh socialite Elizabeth Rees-Williams who in footage alongside her now husband Jonathan Aitken is one of the main interview subjects here. As well as a recent interview with Tsai Chin herself, the other main interviewee is the late lawyer Carlo Colombotti, a personal friend and a wealthy lawyer who moved in the same London circles in the sixties.

Her story, although it contains specific international and cross-cultural reference points, is, basically, an actor’s life: early success on stage and screen through the fifties and sixties, followed by a period in the seventies and eighties in relative obscurity and a later period when her rediscovery by Hollywood in the nineties restarted her career.

An early break was being cast as the lead in the play The World Of Suzie Wong in London’s West End which turned her into a star overnight and helped her secure a director’s job for her then husband Peter Coe. A deal with Decca Records led to a recording of The Ding Dong Song, a massive hit.

Other songs followed – this documentary is peppered with them – as well as notable cabaret appearances at London’s Quaglino’s restaurant. Although Chin is Chinese, much of her work is in Western films, here illustrated by numerous film clips. She played adopted Chinese daughter of Christian missionary Gladys Aylward (Ingrid Bergman) in The Inn Of The Sixth Happiness (Mark Robson, 1958) and a Singapore prostitute servicing British troops in The Virgin Soldiers (John Dexter, 1969). She played the daughter of Fu Manchu (Christopher Lee) in five movies (1965-69). She was the first fully Chinese Bond girl (and the first Bond girl this writer ever saw on screen – to say she had a devastating impact would be an understatement) when she appeared at the start of You Only Live Twice (Lewis Gilbert, 1967). “Stereotypical Asian roles”, says playwright David Henry Hwang.

And then, from 1972 to 1993, an absence from the movies – partly fuelled by the lack of decent roles for Asian women in the West. Also, the 1970s was the decade in which her father was killed by the Maoist purges, she lost her house in the financial crash and her mother visited London, walked out of her life and died in China.

Chin moved to the US to work for a while as a “glorified waitress” for her brother, successful restaurateur Michael Chow (“by that time he was a bit full of himself”) but the clash of egos in sibling rivalry proved too much. An anonymous Boston job as a secretary didn’t last long when her co-workers spent their lunchtimes gossiping about movie stars she couldn’t bring herself to tell them that she knew. Hankering after treading the boards, she found herself working in experimental theatre.

In the early eighties, a meeting with Arthur Miller and her father’s old colleague Cao Yu secured her an academic post teaching theatre, something she relished. Towards the end of the decade, after revisiting Shanghai, she was back on the London stage playing the lead in Madame Mao’s Memories. Her role in The Joy Luck Club (Wayne Wang, 1993) restarted her screen career with a bang and she’s been busy on stage and screen ever since, highlights including another Bond movie Casino Royale (Martin Campbell, 2006), the fifty episode Chinese small screen adaptation Dream of the Red Chamber / 红楼梦, (Li Shaohong, 2010) and, too recent for this documentary perhaps, recent US indie Chinese language pot-boiler Lucky Grandma (Sasie Sealy, 2019).

The film-makers make no attempt to address the fact that in London she seems to have fallen in with an extremely wealthy crowd, no doubt partly due to her own well-off Chinese background. I mention this because the UK both in the postwar period when Chin attended RADA and today has a problem with the arts only being available to the rich, which means that poor people’s voices remain widely unrepresented. (It was perhaps more democratic in the sixties and the decades following, but alas is less so now.)

The film does however touch on the anti-Chinese sentiment Chin encountered in London, with the actress recalling being told on looking at a Bayswater flat that “we don’t rent to foreigners”. Many of the roles available to South East Asian actresses in the West at this time were heavily stereotyped as unintelligent and or prostitutes, which biases the fiercely intelligent Chin didn’t let stand in the way of her career. It also mentions a little about her marriages and her life as a single parent, parenthood being something she abandoned as incompatible with her pursuit of an acting career.

The core interview material (recent and quite lengthy interviews with Chin herself, Rees-Williams, Aitken and Colombotti) are supplemented by a wealth of film clips and archive material. It’s fascinating both as a look at an actor’s life, weaving in between stardom and obscurity, and as a tale of an Eastern woman coming to and making her way in the Western world.

Daughter Of Shanghai is available to rent online in the new Chinese Cinema Season 2021 until Wednesday, May 12th in the UK & Ireland as part of the Approaching Reality documentary strand.