Director – Krzysztof Kieślowski – 1993 – France – Cert. 15 – 94m

*****

A woman who survives the car crash which kills both her composer husband and their young daughter finds herself financially secure and free to do…nothing – 4K restoration is out in UK cinemas on Friday, March 31st

This represents the first part of a trilogy based on the three colours of the French national flag, with each film representing one of that nation’s three values of liberté, égalité, fraternité (liberty, equality, brotherhood). I first saw the film on its UK release back in 1993, for which I interviewed Kieślowski. It’s possible I’ve seen it again in the interim. These days, the trilogy is elevated to the status of a cinematic masterwork. As a young thirtysomething, I remember feeling quite mixed about it. But your perception of these things can change with time, and watching the film again in 2023, in full, restored 4k glory prior to reissue on Blu-ray, I was far more impressed with it than when I first saw it.

For one thing, on this occasion I’m not seeing it for the first time, so the brief appearance (in the courtroom sequence) of Karol Karol (Zbigniew Zamachowski) and Dominique (Julie Delpy) immediately conjures the second film Three Colours: White (1994) in which those characters are the two main protagonists, which wasn’t the case on first viewing when no-one knew what was coming in the second and third films, the third being Three Colours: Red (1994).

A family – Julie (Juliette Binoche), her husband and their young daughter – are on a long distance car journey. The car develops a fault and crashes. Julie wakes in hospital to learn that her husband and daughter are dead. Her husband was a successful composer working on a European commission due for performance in due course, and she has no money issues. The question is, how will she use her new-found freedom?

Freedom, in the abstract, is something people aspire towards, are even prepared to die for. But the freedom in which Julie suddenly finds herself is rather different – her life as it was has been ripped away from her in an instant, her family is gone, she is absolved from matrimonial and parental responsibility. Recovering physically but not, perhaps, emotionally, she comes to the conclusion that human interaction is a trap. She resolves to live alone, with no ties or relationships to anyone else.

She contacts her late husband’s assistant Olivier (Benoit Regent) who has always loved her but never done anything about it. She initiates a one-night stand with him in her family’s large house in the country, all but empty save for a mattress because she has thrown everything out. The act is an act of personal purging for her, because while he might wish to embark on a relationship, she doesn’t want to have anything to do with other people and soon vanishes from his life, moving to Paris without giving him her contact details.

She decides to sell off the house in the country and rent herself a spacious Paris apartment, but doesn’t want to be bothered with the other tenants or any concerns they may have as a group, refusing to sign a petition to evict one of the other tenants, Lucille (Charlotte Véry), a woman branded a whore by the others. (It’s not clear if she’s a prostitute or simply promiscuous and sexually active, although she does, it later turns out, work as an erotic dancer in a nightclub, catering, in all probability, to a largely male clientele.) Without Julie’s signature, the other tenants can do nothing since any decision needs to be unanimous, and Julie finds herself befriended by Lucille. She has walked, unwittingly, into the interaction trap she wished to avoid.

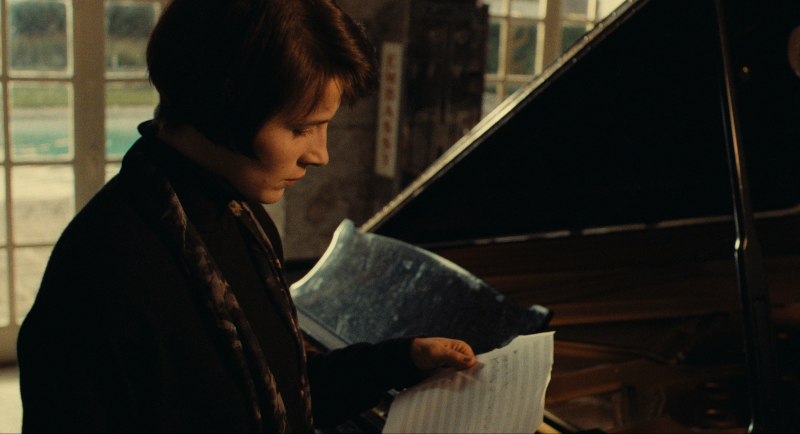

While the narrative follows Julie and her post-bereavement life, somewhere on the fringes of the film, the abandoned Olivier remains in love with her and is looking for her. He also takes it upon himself to rescue her husband’s music scores before they can be destroyed, and works on completing his commissioned European composition. However, it increasingly looks to us as though it was Julie, not her husband, who wrote the music. Will she somehow be able to reconnect to her art, to people around her, to society itself?

The fatal car journey at the start is staged as mundane, which is probably how such things are experienced in real life. Hitchcock talked about movies as being “life with the dull bits cut out” and a car journey falls in that strange space in between significant moments of our lives. Except that, in the event of a fatal car crash, such moments ARE deeply significant and change things forever. Kieślowski mounts his camera on the underside of the car, where, are a while, we see a sump leaking oil. I make a mental note that if this were my vehicle, I’d need to get it serviced a.s.a.p. Then, in an almost throwaway scene, a bystander watches as screeching tyres play on the soundtrack. We see the aftermath, then Julie awakening in a hospital bed, face scarred.

Despite the scene soon after where in her initial anguish, Julie breaks a pane of glass on a hospital corridor at night, Binoche’s portrayal overall feels mostly detached, not wanting to get involved. She refuses to align with her new building’s residents. She throws some manuscripts of her late husband’s musical score in progress into the rubbish. She watches a busker playing on the pavement. She watches an old lady struggle to feed a bottle into a recycle bin station. When confronted with mice in her apartment, her first recourse is to get her agent to try and get her a similar apartment elsewhere; when that doesn’t work fast enough for her, she feels almost embarrassed about asking Lucille for help.

The discovery of her husband’s mistress Sandrine (Florence Pernel) – via still images used on TV show about him – leads Julie to track down and meet the woman, not as a means of judgement or recrimination so much as part of her slow process of reconnecting to humanity. Ultimately, this will lead her back to both her musical composition and Olivier who is struggling to complete his late boss’ work. The profoundly moving closing sequence plays out against 1 Corinthians 13: “If I have not love, I am nothing.”

The first film in the trilogy has stood the test of time well: seeing the three in order as they are reissued over the next two weeks, in these gorgeous 4K remasters, should prove to be a real treat.

Three Colours: Blue is out in cinemas in the UK as a 4K restoration on Friday, March 31st.

Trailer (original, no subtitles):

Trailer (Criterion):

Trailer (Three Colours trilogy in 4K) Curzon (1m):

Trailer (Three Colours trilogy in 4K) Janus films (2m):