Director – Hayao Miyazaki – 2023 – Japan – Cert. 12a – 124m

*****

During WorldWar Two, a boy bereaved of his mother moves to the countryside with his businessman father where a heron lures him into another dimension to rescue his vanished stepmother – out in UK cinemas on Friday, December 26th

Directors, eh? They make their last film, then, some time later, they go and make another one. The Wind Rises (2013) was supposed to be Hayao Miyazaki’s last film, but three years later, he was working on his next one. And seven years further on, The Boy And The Heron hits cinemas. The Japanese title How Do You Live? comes from a popular children’s novel, a copy of which appears in the film, rather than the film being an adaptation of the novel.

Three years into World War Two, young boy Mahito (Japanese dub: Soma Santoki; English dub: Luca Padovan) loses his mother in a Tokyo hospital fire. Four years into the war, his father (Japanese dub: Takuya Kimura; English dub: Christian Bale) – a businessman who manufactures aircraft cockpits for the war effort – decides to move both his factory and his son out of Tokyo to the countryside where he plans to marry his late wife’s younger sister Natsuko (Japanese dub: Yoshino Kimura; English dub: Gemma Chan). She lives in a vast house with a group of old women, known affectionately as the grannies. Arriving there, Mahito sees a Grey Heron swooping over the porch area and as the days pass, the bird increasingly makes its presence felt around the boy, who in exploring the local area discovers an old tower created by his architect granduncle and generally regarded as off-limits because people have mysteriously disappeared – and sometimes reappeared – there.

When the pregnant Natsuko goes missing in the vicinity of the tower, the heron – who can talk articulately (Japanese dub: Masaki Suda; English dub: Robert Pattinson) and whose body resembles a short, fat gentleman wearing a heron’s head helmet and possessing heron’s legs – lures the boy inside the tower, which turns out to be a magical, alternate dimension complete with a vast sea and a race of man-sized parakeets who delight in cooking and eating tasty human beings…

Although its World War Two framing device makes this sound a little like The Wind Rises, its otherworldly search for the missing surrogate mother echoes the child whose parents are whisked away into an alternate world populated by demons in Spirited Away (2001) and its bubble-like, airborne, floating creatures recall similar animal / spirit minions in Princess Mononoke (1997), in many ways The Boy And The Heron feels more like the films Miyazaki made in the first half of his career in Japan before he became internationally famous. The move from city to country invokes that in My Neighbour Totoro (1988), and there’s an epic feel to the magical other world not unlike that of the world in which Nausicaä Of The Valley Of The Wind (1984) is set.

Yet, while it constantly references earlier Miyazaki films, it’s very much a unique work in and of itself which represents a striking, and quite possibly the final, feature addition to the Miyazaki canon. Its attitude to Japan’s involvement in the war is pretty odd, as if to say that participating in the war was a necessity, but the narrative conveniently forgets about the war most of the time by plunging into an alternate dimension in which much of the action takes place. Yet the war is undeniably there in both the dreams of his mother trapped in the hospital fire which constantly haunt Mahito and the glimpses of workers carrying cockpits to or from his father’s factory. Perhaps it’s also present in the militaristic parakeets, rendered in three or four separate colours, one per bird, to suggest a rigid hierarchy – they are ruled by a parakeet king (Japanese dub: Jun Kunimura; English dub: Dave Bautista) – not unlike an army.

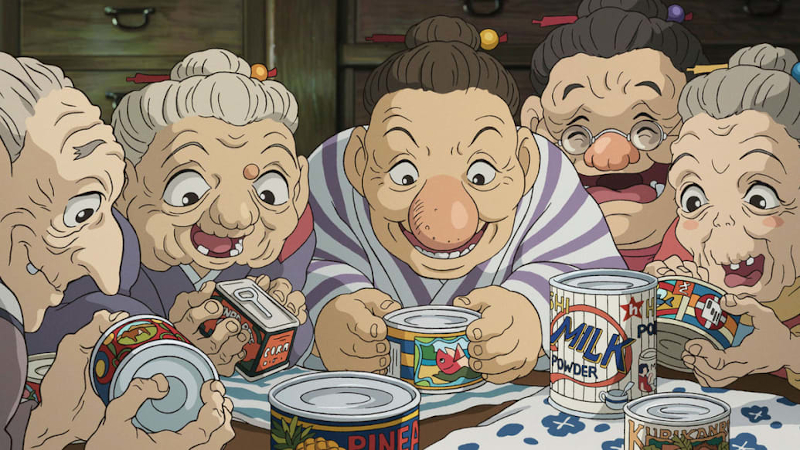

Such elements are contrasted with bursts of whimsy, such as the parakeets escaping into our world and reducing from man size to familiar flying size. Then there are the grannies, visually not unlike Spirited Away’s two old crones Yubaba and Zenibaba minus the grotesque giant heads, but much more good-natured, who feel like they could have wandered in from another film. One of their number, Kiriko (Japanese dub: Ko Shibashi; English dub: Florence Pugh), accompanies Mahito in his journey to the Tower and the world within, but soon disappears only to turn up later as an inanimate talisman who returns to life as a granny on re-entering our own world.

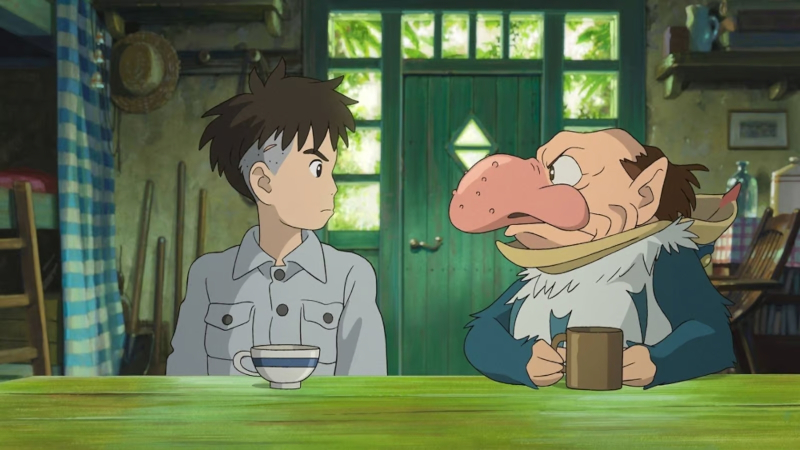

Finally, Mahito meets his granduncle (Japanese dub: Shohei Hino; English dub: Mark Hamill) in the other world inside the tower, an old man who keeps the world in balance by constantly readjusting a small tower built of children’s toy building blocks who is looking for someone to take over the task, which he hopes the unwilling Mahito might fulfil. Perhaps this is Miyazaki trying to come to terms with the fact that he may not be around much longer to make movies, and that no-one else is capable of making quite the movies he does, much as he might wish they would.

There are other subsidiary characters, including a seafaring warrior and an adventuress Himi (Japanese dub: Aimyon; English dub: Karen Fukuhara) and a race of trapped pelicans from our world, ruled by a pelican king (Japanese dub: Kaoru Kobayashi; English dub: Willem Dafoe) within the tower world but for the most part this is the two-hander the title suggests. Mahito is a fascinating and complex protagonist, possibly the most complex Miyazaki has ever created, struggling both with a sense of loss (his mother is dead, while it’s unclear for much of the narrative whether his vanished stepmother, who seems to fulfil a similar role to the children’s hospitalised mother in My Neighbour Totoro, will be rescued by Mahito or lost forever in the alternate universe to which he has journeyed).

The heron is likewise complex, part bird and part human being (or demon or whatever exactly he is supposed to be) and on a first viewing of the film, his motives are far from clear. The innocent boy and the comparatively jaded and cynical heron seem to be playing some sort of game, each constantly trying to outmanoeuvre the other, almost as if they were at war, or participating in an uneasy truce. Darker forces would appear to be at work than in the benign My Neighbour Totoro.

Far more focused on its dual characters than the much more scattershot Spirited Away with its cast of thousands, this may well be closer to Nausicaä Of The Valley Of The Wind than to anything else in Miyazaki’s back catalogue. It’s Miyazaki’s strongest film since the early 1990s, and if, as seems likely, it indeed turns out to by his final feature, it’s a very good note on which to go out. It consolidates his earlier body of work while standing as a masterpiece in its own right.

The Boy And The Heron is out in cinemas in the UK on Friday, December 26th. This review is from watching the Japanese version subtitled in English; the names of the English language voice actors are included for reference.

UK English language trailer :

UK Japanese language teaser trailer: