Director – Marco Bellocchio – 2023 – Italy, France, Germany – Cert. 12a – 135m

*****

A boy is forcibly taken from his Jewish family by the Pope to be raised as a Catholic priest because he has been baptised into the Catholic faith – out in UK cinemas on Friday, April 26th

Italy, the mid-nineteenth century. The Papal States will have disappeared by 1870 as Italy moves towards unification. In the meantime, they are still under the administrative control of the incumbent pope, Pius IX.

Bologna, 1852. A maid sees off a soldier in the night following a romantic tryst. The soldier is neither here nor there; the maid, Anna Morisi (Aurore Camatti) will play a significant part in what follows. The life of a nine-child Jewish family is about to be disrupted forever.

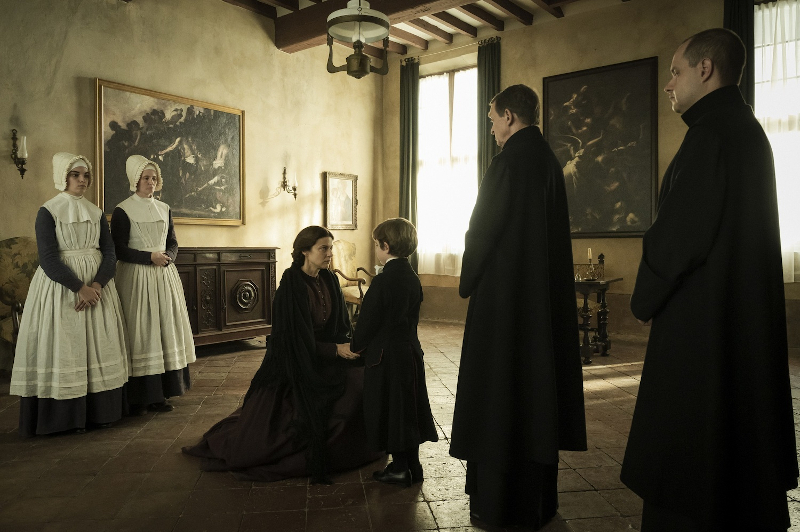

The home of the very ordinary Mortalo family, who are Jewish: father Momolo (Fausto Russo Alesi), mother Marianna (Barbara Ronchi) and their nine children. The parents are deeply religious and raise their offspring accordingly, teaching them, among other things, to recite the Shema prayer every night before they go to sleep. One night in 1858, they are visited by the authorities under Feletti (Fabrizio Gifuni) who have come to take away one of their children under Papist law. The parents are officially informed that that their son Edgardo (Enea Sala) has been baptised a Roman Catholic, and it is therefore the duty of the State to remove him from his Jewish family and raise him as a Catholic.

The parents are assured that their son will be given a new home somewhere in the city where they will be able to visit his regularly, but this is a lie: after a 24-hour respite granted the family to give them a little time to come to terms with their new situation, the child is swiftly taken away the following night under cover of darkness to a Catholic boarding school in Rome where Jewish boys are instructed in the Catholic faith by none other than the Pope himself (Paolo Pierobon). Determined to remain true to the faith of his parents, Edgardo secretly recites the Shema under the bedclothes every night in the dormitory. During the day, he and his fellow pupils are required to attend Catholic services and recite liturgies in Latin.

Edgardo is swiftly befriended by one of the boys, who offers advice about how to survive and give the school authorities what they want. He plays along, but, perhaps inevitably, the Catholic schooling to which he is being exposed slowly seeps into his consciousness even as he tries to keep his Jewish heritage alive. At one point he has a vision in which he approaches the statue of Jesus Christ crucified, who he has now been taught as having been killed by the Jews, and removes the nails from the statue’s hands and feet. As the years pass, he slowly undergoes conversion to Catholicism so that, by the time he is a young man, Edgardo (Leonardo Maltese) is ordained as a priest within the Catholic Church.

Throughout this time, Momolo has endeavoured, unsuccessfully, to get his son back; in his heart of hearts, however, he feels this to be an impossible task and when he meets with his young son, there is about him an air of resignation as if her were the boy’s former father. He has lost hope. Marianna is, however, made of stronger stuff, and when she later visits the boy she embraces him to such a degree that he must be forcibly dragged away from her. This leaves a strong emotional mark on the boy: he will forever be his mother’s son, and however much he is outwardly a Catholic, he will remain conflicted between his natural Jewish family and his enforced Catholic one.

It turns out that Anna Morisi, who briefly worked as a maid for the Mortalos, fearing that the child when he was ill was about to die and therefore, as a Jew and a non-Christian, was also about to go to Limbo, was advised by a local pharmacist that her duty as a Catholic was to enact the ritual of baptism and save the child. She reported all this to the Church authorities in 1858, initiating the child’s abduction by the Papist State.

As the rule of the Pope is overthrown in favour of the that of the new Italian State, the wall between the school and the world outside is torn down. Edgardo runs into his brother Riccardo (Samuele Teneggi), now a fighter against the Papists for a unified Italy, who has renounced religion altogether. In 1878, later, accompanying the procession of the body of the deceased Pius IX, Edgardo suddenly and surprisingly find s himself momentarily switching sides to join with protestors in chanting that the late Pope’s body be thrown into the river. He is still conflicted between his two ‘families’, his two religions, his two ethnicities; so much so, that when visiting his mother, on her deathbed and remaining a faithful Jew to the last, he attempts to convert her to Catholicism.

This is a terrifying film and arguably as powerful a picture of antisemitism as has ever been portrayed on the screen. It’s also an indictment of what happens to Christianity and the Christian (in this instance the Catholic) Church when it gets into bed with power structures. In the main, there are only really two religious viewpoints presented here. A third, the atheism of Edgardo’s grown-up brother Riccardo, is touched upon, but only briefly and not given the space where much more can be done with it than acknowledging that it exists. Director Bellocchio seeks to explore and understand both the Judaistic and Catholic mindsets, with considerable research and attention to detail in both camps so that both parties convince on the screen.

There’s something almost despotic about the arrogance of the Catholic ruling authorities, as displayed here. To a modern Western sensibility with an understanding of respecting different ethnic cultures and their accompanying beliefs and practices, provided those practices don’t embody any sort of hate directed against other ethnicities, they sound a wrong note, but the Catholic authorities of the day did not see things that way. Their world view would appear to encompass the idea of non-Christians (non-Catholics) requiring salvation, and that only being possible through Catholic ritual. And once a person has been baptised into the Catholic faith, they must then be removed from the corruption of other faiths such as, for example, Judaism. It’s appalling, but that’s the thinking.

Director Bellocchio understands this mindset and quite brilliantly articulates it through the behaviour of his Catholic characters. Pius IX and those beneath him may be totally misguided, but Bellocchio comprehends how they get there. However, he is equally thorough when showing us the Jewish family. Before Edgardo is taken away by the Catholic authorities, his father presses a metal object into his hand, telling him to keep it with him at all times. That appears to be a portable version of a Mezusah, a small object with a Hebrew prayer contained inside, the significance of which to Jews is not dissimilar to that of a crucifix to Christians; in short, a religious artefact, an expression of their faith. (A Jewish person could probably explain this more accurately and succinctly than I.) Changed into a shift to sleep in the Catholic dormitory for the first time, he drops it and hopes the nuns in charge of him won’t notice. When they’ve gone, he hides it under his pillow.

One of the other boys in the dorm is sick and largely confined to his bed. The boy is well looked after, in part because his mother has converted from Judaism to Catholicism. When the boy dies, his supposed converted mother slips a Mezusah inside his corpse’s clothes. It seems she hadn’t converted at all, but was just playing along as a means of survival in a Catholic-administered world.

Sala is extraordinary as the boy, conveying the sense of being completely torn between his old and new ethnic / religious identities. Bellocchio’s film is in the Italian language; before he embarked upon the project, celebrated Hollywood director Steven Spielberg was planning to make an English language version of the story, but eventually abandoned it when he couldn’t find a suitable (English-speaking) child to play the part. While one wonders what the Spielberg version would have been like, we should be thankful that we have Bellocchio’s film because of his deep understanding of both religious ethnicities involved and the administrative machinations of the day within the wider historical context.

It’s a particularly tough watch for anyone with roots in either Christianity or Judaism, and I would hope challenging viewing for anyone with an interest in freedom of belief (which, frankly, ought to be everyone). Since its Italian theatrical run in 2023, recent historical events in Israel and Gaza have made the film appear even more relevant, with its themes of antisemitism and of one ruling religious / ethnic group lording it over another. Before those events, it was already a must-see; in the times wherein we now find ourselves, even more so.

And if anyone is in need of arguments in favour of separating church and state, this film is a very good place to start.

Kidnapped is out in cinemas in the UK on Friday, April 26th.

Read my shorter review for Reform magazine.

Trailer: