Director – Clair Titley – 2023 – UK – Cert.12a – 90m

*****

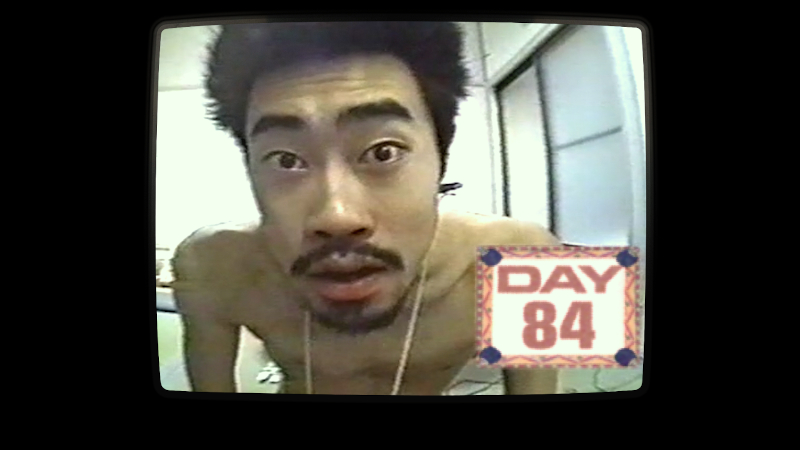

How a man’s incarceration in a room, broadcast on TV, became a media sensation in Japan– out in UK cinemas on Friday, November 29th

Before The Truman Show (Peter Weir, 1998), which would be released later the same year, a couple of years before Big Brother and the start of the UK’s reality TV phenomenon, a Japanese TV show breaks new boundaries. A man is put in a room where he had to earn a million yen in prizes from magazine competitions before being released. The facilities are basic – there is a sink unit and a gas ring, but no cooking utensils. The whole situation is filmed by two cameras. The man in the room, Nasubi, knows it is being filmed, but has been told by the producer that most of it will be thrown away. He is completely unaware that this setup is being edited into a weekly, six-minute TV spot and going out on the weekly, magazine format, endurance TV show Denpa Shonen.

The Denpa Shonen show is the brainchild of TV producer Tsuchiya, who for this segment auditions a dozen or so male hopefuls and chooses one of them, Nasubi, by lottery. Nasubi is told that the show is primarily about luck, and that all he has to do is meet his million yen target. He is taken to the room where the cameras are running. He is ordered to remove his clothes (“What? All of them?”), an instruction which conflicts directly with the promise made to his mother Kazuko who instructed him, whatever he did in the entertainment world, to keep his clothes on. He feels an understandable degree of shame about this. But since, as far he knows, this isn’t going to be broadcast, it should be fine.

As he moves around the little room, a solid black circle is used to cover his genital area, soon changed to an eggplant image. (‘Eggplant’ has subsequently become a euphemism for ‘penis’ in Japan, probably as a direct result of this.) We watch as Nasubi struggles with hunger, share his joy at the first time he wins a prize, 12 cartons of fibre jelly. The next thing he wins is a bag of rice, but lacking a saucepan to cook it in proves a problem. Soaking the rice in hot tap water doesn’t work, but he fares better when he tried warming a carton of soaked rice near a gas flame, which cooks the rice.

As the ratings soar, his mother is completely unaware of the show, while his sister Ikuyo is both shocked and embarrassed. His childhood friend Anzai is glued to the TV, commenting on Nasubi’s natural aptitude for appearing before the cameras. 50 days in, Nasubi is exhausted. He writes a diary all this time, and his comments appear on the screen. He talks in retrospect about feelings of isolation and loneliness, which were edited out of the material which aired. Every time he wins something, he dances around the room with joy, unaware that these dances are becoming a regular feature of the show and part of his television persona. As the internet starts to question whether he’s in the room 24/7, producer Tsuchiya hits on the idea of livestreaming the Nasubi camera over the internet.

On some level, Nasubi is a wiling participant in all of this: the door isn’t locked, and he could have walked out at any time. Yet, as he points out, it’s easier to play along rather than cause a fuss and upset things. The morning after he unwittingly reaches his target, Tsuchiya wakes him with a flashlight, whisks him off blindfolded to another room, in South Korea, and starts the whole thing over again as Nasubi’s challenge in Korea, this time with the cost of an air ticket back to Japan as a goal.

It’s hard to look sympathetically at Producer Tsuchiya’s work, which appears to be a combination of bullying and manipulation for the purposes of catching something on camera to up the ratings, regardless of the human cost on the person concerned. Nasubi comes off rather better, finding his path as a media personality achieving his own self-mounted challenges, such as climbing Everest, as a means to encourage the people of Fukushima, the area he came from, in the aftermath of the earthquake and the tsunami.

Director Clair Titley has assembled all the necessary interview subjects – Nasubi, his mother, producer Tsuchiya, mountain guide Kendo who worked with Nasubi on his Everest exhibitions, and BBC Tokyo correspondent Juliet Hindell. The latter attends Nasubi ‘s press conference – which turns out to be more like a TV show with an audience – after the Korea challenge and his total 15-month ordeal, to ask, did you struggle mentally?

While one can talk about Nasubi’s complicity and praise him for what he did afterwards, this still feels like an appalling act of abuse being perpetrated upon him. When he says things like, “I knew I was broken,” your heart goes out to him because it’s difficult to read the situation any other way.

Made for English-speaking viewers, the documentary replaces onscreen Japanese language TV captions and slogans with English ones, which is helpful since we don’t really have an equivalent here (the nearest I can think of is the crass slogans in 1950s Hollywood movie trailers). The subtitles in the show footage appear to be translations of Japanese subs rather like the rolling legends at the bottom of US TV news screens (but different). All these peculiarities land the piece a unique feel to anyone not used to watching Japanese TV shows.

The whole phenomenon documented here is nothing less than jaw-dropping, and the documentary well paced and put together. Perhaps watching the film makes the viewer complicit in what happened to Nasubi. Either way, as I’m sure producer Tsuchiya would be the first to agree, it makes for compelling viewing.

The Contestantis out in cinemas in the UK on Friday, November 29th.

Trailer: