Director – Maryam Touzani – 2022 – Morocco – Cert. 12a – 122m

****

A love triangle between a gay dressmaker, his wife and the man’s new apprentice, a movie which deserves to be cherished for a wide variety of reasons – out in UK cinemas and on BFI Player (rental) from Friday, May 5th

Halim and Mina (Saleh Bakri and Lubna Azabal) run a traditional clothing store in the street of one of the oldest medinas in Morocco. He inherited the store from his father, a maleem or master craftsman, and laments the fact that, with the rise of modern technology, the old skilled craftsman is dying out as people can buy the same products, made instead by machines, for lower cost. He gets very excited when his new apprentice Youssef (Ayoub Missioui) turns out to possess a rare aptitude and enthusiasm to learn those skills.

At the same time, Halim has a secret: in a conservative Muslim country where homosexual acts constitute a punishable offence, he is a gay man. He loves his wife dearly and would do anything for her, but his preference is for those of his own gender. She has learned to live with the fact. He takes trips to the local bath house where he engages in gay sex with others in the privacy of the cubicle booth.

Watching their day to day activity in the shop, it’s clear that she is the one who knows how to deal with difficult (usually female) customers, while he, although a gifted craftsman, might not possess the same level of business skills as she. But there is a further problem: she is ill with cancer; she has had a mastectomy and it may only be a matter of time before cancer kills her.

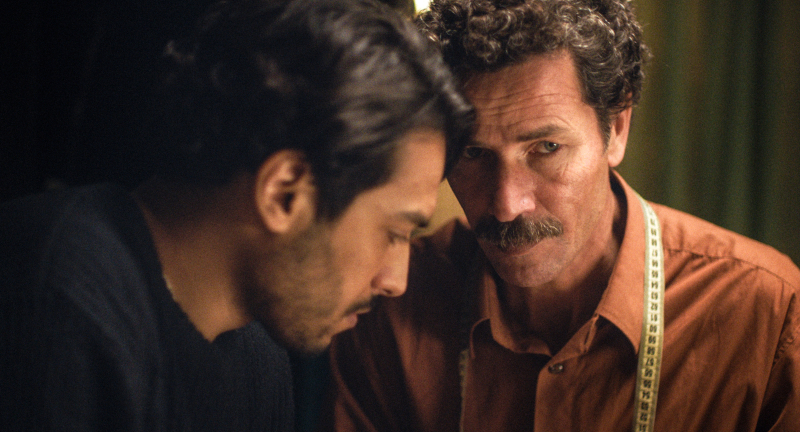

Halim, meanwhile, finds himself attracted to Youssef.

That may not sound like a particularly original story, and in a way it isn’t – it’s basically a love triangle – yet co-writers Touzani (also the director) and Nabil Ayouch (also the producer) go into various aspects of the story at such depth that the results are compelling and, in the final reel, devastating. For a start, there’s a great sense of place to the narrow streets and small rooms, and a real feel for the specific craft and clothes making that Halim embodies. The film is also extremely accurate on the perils of running a small business and dealing with difficult customers (including the wife of a corrupt local official).

The relationship of vulnerable husband and protective wife is conveyed in two performances that are note perfect, the characterisations extending in the wife’s case to a deeply devout religious (Muslim) woman who nevertheless has come to terms with the complexities of her husband’s homosexuality in a way that he himself perhaps never has. Furthermore, whereas in many filmed love triangles the characters are fundamentally selfish and don’t care about the damage the inflict on others in the pursuit of the fulfilment of their own desires, here the three protagonists are to a woman concerned with the effect their actions might have on the well being of the other two, which is refreshing indeed.

The film is made from a Muslim perspective, but is unafraid to acknowledge that there might be a great deal wrong with the basis on which the more conservative Muslim societies (countries) are run without the filmmakers throwing all manifestations of that religion out of the window. Indeed, the closing scenes are so profoundly moving that as someone who similarly practices Christianity while simultaneously despairing at many of its more conservative manifestations I felt a great deal of sympathy towards the journey the film undertook and the destination at which it eventually arrived. You might think of it as a grown up religious film.

And then there’s the portrayal of illness and various medical aspects, including mastectomy, about which I don’t want to say too much as it would detract from watching the film for the first time, except that there are difficult and possibly even taboo issues here which the film handles with great sensitivity.

There is nothing about the film that suggests a vast budget or great expenditure, but much about it that suggests considerable knowledge of craft both in front of and behind the camera by all concerned, including cinematographer Virginie Surdej who is clearly another major player in realising the film’s vision. There is an iconic quality here. The only film I can think of that is remotely like it – and it’s a very different film which hails from an utterly different culture – is In The Mood For Love (Wong Kar-wai, 2000) with its narrow streets and repressed sexual longing; The Blue Caftan is, however, very much its own film, a unique vision and one to be cherished for a wide variety of commendable reasons, some artistic and cinematic, some much more specifically human.

The Blue Caftan is out in cinemas and on BFI Player (rental) in the UK from Friday, May 5th.

Trailer: