Director – Lee Sang-hak – 2024 – South Korea – LKFF Cert. 15 – 97m

*****

A Christian mother, her ‘Christian book’ author son, and her local pastor brother-in-law are haunted by traumas from their collective past – suspense thriller from LKFF, the London Korean Film Festival 2024 which runs in cinemas from Friday, November 1st to Wednesday, November 13th

—

I don’t often preface a film review with a piece of verbal, religious text, but in this exceptional case, the following Old Testament quote may be pertinent, particularly the phrase in bold:

The Lord passed before him and proclaimed, “The Lord, the Lord, a God merciful and gracious, slow to anger, and abounding in steadfast love and faithfulness, keeping steadfast love for thousands, forgiving iniquity and transgression and sin, but who will by no means clear the guilty, visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children and the children’s children, to the third and the fourth generation.”

– Exodus 34:6–7

—

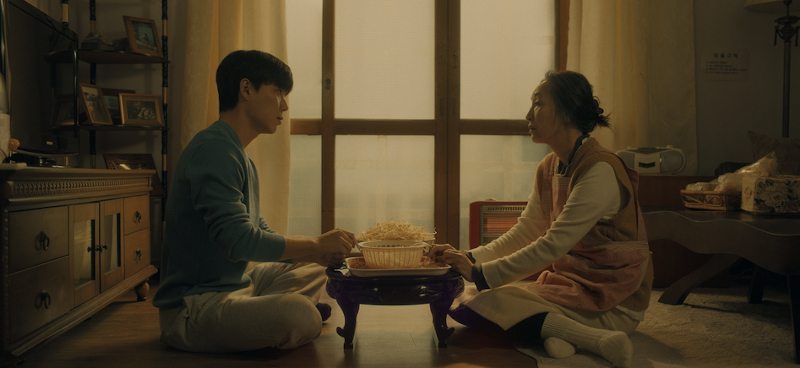

Ji-wook (Han Ki-jang) lives with his mother Kyung-hee (Nam Kee-ae), and although he’s earning a respectable living working from home as a writer of self-help motivational books, in many ways he seems deeply unqualified to be peddling such advice to a wider public. He has never left home – in fact he seems incapable of doing so – and relies heavily on his mother for all manner of things. This is not a good situation, especially given that she’s getting on in years and (as a visit to the doctor confirms) suffers from early onset dementia.

Kyung-hee runs a ladies’ hairdressing salon called The Kingdom, so she’s familiar with the ins and outs of running a business, which is probably where her son picked up the rudiments. Her family (her and her son) is one little kingdom, the salon a second, and the local protestant Christian church a third – or it was, because at some point she seems to have abandoned it, a state of affairs which comes to light when she’s visited by her brother-in-law Joong-myung (You Seong-joo), a local Pastor. He is unmistakably and deeply Christian, and it’s not that she isn’t, exactly, it’s more as if something has happened in the past to drive her away from the institution of the Church or the people associated with this local iteration of it.

Besides, her son’s motivational books, such as The Power of the Truth, have a clearly Christian slant to them. They are aimed at the Christian market and are what some people in certain religious circles like to refer to as ‘Christian books’. Disturbingly, before the narrative has run its course, he will later (in what is possibly a dream sequence) promote a follow-up volume with the title The Power of the Lie.

With his sister’s memory being on the verge of vanishing little by little, Pastor Joong-myung wants answers to troubling questions about the past, specifically regarding his brother who walked out on his sister-in-law all those years ago. The problem is that his brother appears to have vanished into thin air at the point he left the relationship, and if she knows where her husband went, his sister-in-law isn’t telling.

The domestic set-up with her son is downright peculiar. Kyung-hee has a set of rigid rules, which she insists he follow for his own good. From time to time he is troubled by a recurring bad dream, which she encourages him to put aside on waking with an upbeat, positive slogan, which, again, is perhaps none too distant from the place from where some of his self-help philosophy comes. Perhaps, however, there’s something in the shared past of the mother and the son that both of them are failing to confront.

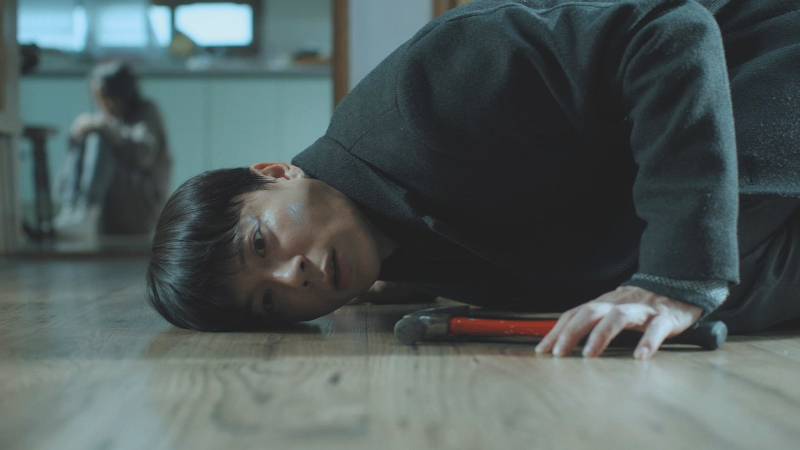

Director Lee piles on the tension with the skill of a Hitchcock, but that statement doesn’t really do the film justice because, unlike Hitchcock, it’s incredibly gentle and tender in tone, at least superficially, while the darkest of passions, including retribution and murder, rage beneath the tranquil surface. It reminded me a lot of Spellbound (Alfred Hitchcock, 1945) in which a character’s obsession with a repeating motif of lines, or stripes, is explained towards the end of the narrative by a brief, devastating, cathartic flashback of a traumatic incident from the character’s childhood.

Spellbound, however, is set within the speciafic context of a psychoanalyst / patient relationship, where the doctor is in love with the patient, with no obvious religious overtones – whereas Mother’s Kingdom is set within the context of a past abusive relationship with obvious past, and present, religious overtones. Where Spellbound hurtles toward a happy resolution, however traumatic the journey to get there, Mother’s Kingdom explodes into a series of, to use a Christian analogy, personal hells. The final moments offer a glimmer of hope, but no more than that.

Mother’s Kingdom also works on a whole other level. It’s fascinating from the point of view of Christianity, in this case a deficient Christianity with an Old Testament emphasis on judgement and punishment rather than a New Testament emphasis on grace, because the brother-in-law pastor finds himself lacking the tools to cope with the pain and harsh realities of his family history, his sister-in-law’s long-standing resolve to keep quiet starts to crumble as her repositories of memory begin to melt away, and everything that the son has used to hold it together over the years threatens to fall apart and leave him defenceless.

All the characters here desperately need a more robust and thought through version of the Christian faith, and more specifically of the Christian God, to help them, but their small, personalised, institutionalised or post-institutionalised versions of Christianity don’t afford them the necessary spiritual space to manoeuvre and grapple with the issues involved.

It’s not quite the Catholic guilt in which Hitch so often traded, but as the piece moves into traumatic memories, other dysfunctional family dynamics, and hanging, it articulates ideas about relationship breakup, individual isolation within certain Christian churches, and how families can sometimes be cut off from the rest of the world.

The only film I can think of that comes anywhere near it in these terms is the drama Apostasy (Daniel Kokotajlo, 2017). However, that sets itself up as a drama about a specific religious group (Jehovah’s Witnesses), whereas the initially deceptively gentle Mother’s Kingdom is unmistakably a thriller which operates against a backdrop of more conventional, protestant churchgoing.

For those with no religious or Christian affiliation, this should play out effectively enough as a thriller; for those adhering to a Christian faith of one sort or another, it may deliver an altogether more complex and nuanced experience.

Mother’s Kingdom plays in LKFF, the London Korean Film Festival 2024 which runs in cinemas from Friday, November 1st to Wednesday, November 13th.

Trailer (no subs):

Trailer (LKFF 2024):

Trailer (Echoes In Time | Korean Films of the Golden Age and New Cinema):