Director – Magnus Van Horn – 2024 – Denmark, Sweden, Poland – Cert. 15 – 123m

*****

A young Copenhagen woman’s attempts to escape poverty following the Great War lead her into a dark nightmare – Denmark’s entry for Best International Feature is out in UK and Ireland cinemas on Friday, January 10th

In the darkness, faces writhing, superimposed on other faces. Katherine (Vic Carmen Sonne from Godland, 2022; Holiday, Isabella Eklöf, 2018), behind on the rent for her room by 14 months, is evicted. She works at a rag trade factory as a seamstress, where the owner Peter (Besir Zeciri) wants to be able to help her but cannot grant her widow’s supplement without proof of death of her husband, who has gone missing in the war. She manages to find herself cheaper lodgings. Sensing something more behind Peter’s kindness and an offer of a shoulder to rest on, Katherine has sex with him in an alley in broad daylight.

One day, her husband Jørgen (Joachim Fjelstrup) returns from the war, his face heavily disfigured. She takes him in but, unable to cope with his recurring nightmares, soon throws him out. Something similar is soon visited on her; Peter agrees to marry her, but when his mother (Benedikte Hansen from Borgen, TV series, 2010) explains that her son can do as he wants, but not with her money or her estate, he changes his mind (this, incidentally, is the same plot that drives Anora, Sean Baker, 2024). Soon after, a letter tells her her services are no longer required at the factory.

Lying in one of the tubs in the public bath house, she attempts to induce an abortion by plunging a knitting needle between her legs into her womb, only to be stopped by fellow customer Dagmar (Trine Dyrholm from Festen / The Celebration, Thomas Vinterberg, 1998) who is there with her young daughter Erena (Ava Knox Martin). Dagmar offers to help Katherine place her baby with foster parents, if she would like that. Dagmar explains it’s a business she runs, so there is a fee.

Katherine is later working as a casual labourer carrying vegetables in a factory when she gives birth. She takes her daughter home, where Jørgen asks to hold the baby and names her. Within a day, she has taken her to Dagmar, who operates out of a sweetshop, to be passed on to someone who can afford to care for the baby and its upbringing. When she offers to wet nurse the babies before they go to their foster home, Dagmar lets her breastfeed the seven-year-old Erena in exchange for board and lodging.

However, Katherine’s journey into nightmare is only just beginning, since Dagmar and her child fostering service are not quite what they seem…

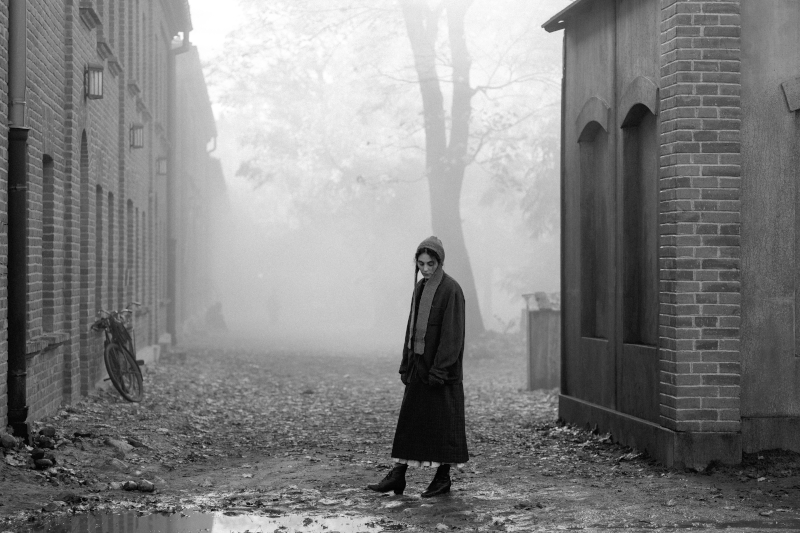

Shot in arresting black & white by cinematographer Michal Dymek in various hilly Polish cities standing in for the flat Copenhagen, the tale is at once inspired by a notorious, real life Danish crime case and a milieu in which Von Horne (Sweat, 2020) can explore a world governed by nightmarish, fairy tale logic.

Its writhing faces at the start, its black & white cinematography, its sense of historical period and detours into the world of circus freak shows (to which the disfigured Jørgen submits himself to earn a living and in which he finds some sort of community which accepts him for what he now is) all recall The Elephant Man (David Lynch, 1980). The circus freaks specifically invoke Freaks (Tod Browning, 1932). Its black & white sense of period is also reminiscent of The White Ribbon (Michael Haneke, 2009), although that film lacks the dreamlike qualities of this current one.

There are also similarities with The Story of Sin (Walerian Borowcyzk, 1975), although to say more about those would constitute a spoiler.

And yet, for all its recognisable sources, intentional or otherwise, it feels like a highly original work, fixed very strongly in a specific time and place (much as The White Ribbon was); here, Copenhagen in the aftermath of WW1, a time when there was no safety net for the destitute so people, particularly women, did what they had to do in order to survive.

The film doesn’t pull any punches and much of the material is both deeply disturbing and even, in places, shocking. There are many social provisions in today’s Denmark and other Western countries which simply did not exist in 1919, and this film provides a convincing and terrifying snapshot of how things might be if those provisions were taken away or had never existed. Even more than The Story of Sin, it may be one of the starkest and most moving depictions of the social evil of want ever to have been realised on the screen.

Parts of the film are deeply distressing in the manner of the worst imaginable nightmare. The film may upset some, but is highly recommended for those who find fairy tales or horror narratives compelling. Whatever else the film may be, it doesn’t make for pleasant viewing. And it’s about as different from the director’s earlier Sweat as it’s possible to imagine.

The Girl with the Needle is out in cinemas in the UK and Ireland on Friday, January 10th.

Trailer: