Director – Ayumu Watanabe – 2021 – Japan – Cert. PG – 97m

*****

A large, single parent mum continues to make bad relationship choices as her daughter tries to make her way in the Northern Japanese coastal village where they currently live– out in UK cinemas on Wednesday, August 10th

Charging in its opening minutes in rapid-fire, riotously paced colour through the love life of large lady Nikuko (voice: Shinobu Otake) – whose name given by her daughter translates roughly as Meat-lady, a reference to her size and resultant huge appetite – this details her poor, serial, romantic choices via which the various men for whom she falls scam her for money and cheat on her one after the other. Eventually, she falls for The Novelist, who is at least faithful and comes with the added bonus that he’s always spending money on books (not that he’s generating any money himself) which engenders in the story’s voice-over narrator, but not in the woman herself who doesn’t bother with books, a lifelong love of books and reading. But, one day, he unexpectedly leaves, so Nikuko follows his path up north, fails to find him and settles in a small, coastal fishing town. This is the story of my mum, reveals the narrator.

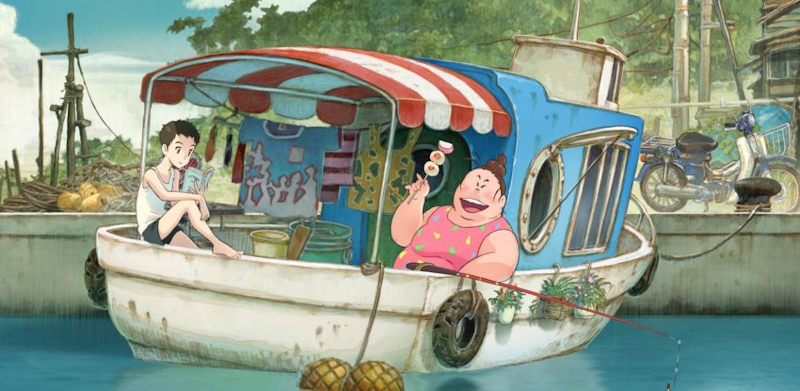

Thereafter, the pace slows down as the film settles for about an hour into a gentle study of life in the one, Northern, coastal town location. Nikuko lives with her pre-menstrual, teenage daughter on a houseboat which she rents from her hard-working but genial and generally good employer boss who runs a local restaurant where she waitresses. She drifts into the background of the narrative as daughter Kikuko (voice: Cocomi) becomes embroiled in complex dramas of friendship and loyalty among her school classmates. Her daily walk to school walk sees her cross the rice fields to meet up at a crossing by a tree with friend Maria (voice: Izumi Ishii). Three boys Matsumoto, Sakurai and Ninomiya (voice: Natsuki Hanae) hang around the tree, the particularly shy Ninomiya given to pulling funny faces when he thinks no-one is looking. Kikuko and Maria get on well, although Kikuko appears to have no other friends at school.

That said, Kikuko is always the first to be chosen for the class basketball team, while Maria is the girl who never picked. Maria puts this down to favouritism towards Kikuko on the part of Kanamoto, one of the girls who picks the teams. Eventually, having had enough of this situation, Maria gets a few other girls together to suggest an alternative, team selection system. She invites Kikuko, Mori and the other girls over to her home for an evening, but Kikuko suspecting her agenda is anxious to get out of the arrangement and, after consulting her mum for advice, makes an excuse about having a cold. Maria is not to be put off so easily, however, and the next morning she and her friends confront Kikuko in the girl’s washrooms to demand that she join their enterprise, something to which Kikuko feels unable to give her assent.

Maria’s plan goes terribly wrong, and she ends up isolated from everyone else including Kikuko, who discovers the fact when out with friends she’s made recently at the Summer Festival where Kikuko, incidentally, is the only one not wearing a summer kimono, a situation with which Kikuko is both comfortable and happy. A that same festival, she also sees her mum get drunk and engage in a long conversation with a food seller, which convinces her daughter that Nikuko is about to embark on another ill-advised romantic liaison which will end up with mother and daughter moving to the next town, something Kikuko doesn’t want to happen since she feels settled in their current location. Confirming her suspicions, she observes her mum on lengthy phone calls when the latter doesn’t think she’d notice.

After spotting Ninomiya on a bus making faces at the window, Kikuko runs into him at the tree, where he shows her a tombstone to Batou Kannan – the guardian of horses – which was moved inland during the tsunami a few years ago. He gets her to walk with him into town rather than taking the bus that she normally would, detouring en route to show her his special place in the forest, which turns out to be an incredible high up vantage point from which a revelatory, panoramic view of the town can be seen. He also shows her the kotobuki centre, a place which has intrigued her without her knowing exactly what it is – on a previous trip, her mother neither knew nor cared, focused as she was at taking them to see their favourite penguin at the animal house – which turns out to a children’s therapy centre where he is making a model (concealed by a screen white-out when he opens the box to show her, so we don’t see what it is until it’s finally revealed to the audience at the end). He’s been told he needs to focus, to get away from his involuntary face pulling. But Kikuko rather likes his face pulling and indulges him by pulling some of her own. He feels he can be himself when he’s with her.

The final half hour includes a lengthy flashback which feels different again from the rapid-fire opening and the generally lazy, light and airy, summery feel of the whole. It’s as if the late Satoshi Kon (Tokyo Godfathers, 2003; Perfect Blue, 1997) had suddenly appeared and imposed his visual style on the film – the characters feel much more solid and intense, with much of the action taking place in small, confined and dimly lit urban interiors. Nikuko falls in with a fortune-teller and the two live together as sisters until a baby appears. Then the other is gone, leaving Nikuko to raise the infant alone.

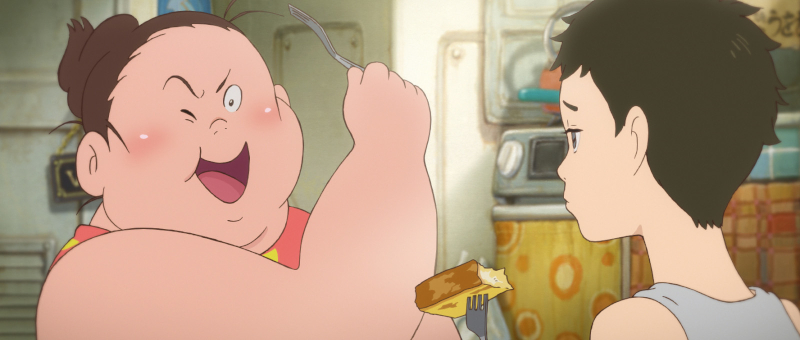

The material about the large meat-lady mother walks a bizarre tightrope between the fat shaming and low intelligence shaming of the mother by the daughter and a love of large, cuddly mothers imported wholesale from the children’s love of the friendly eponymous tree spirit of My Neighbour Totoro (Hayao Miyazaki, 1988), complete with sleeping, snoring and large teeth. There are Japanese language puns which she’s not quite clever enough to get right, so much so in the opening minutes that the non-Japanese speaker starts to worry that they’re going to miss a whole shade of meaning even in this subtitled version. Not to worry, though, this doesn’t keep up and plenty of other things go on to maintain your interest.

There are further Totoro references for a start – buses travelling in the distance seen over rice fields, a sequence of thin daughter and fat mother waiting for the bus in the rain with dark green vegetation behind, a passing ginger cat that immediately makes you think “catbus”, and a shot standing at a window which recalls the mother at the window in hospital at the end of that film.

Then there are scenes in the restaurant which are mouthwatering to watch, featuring the grilling, preparation and serving of various Japanese meat dishes. This will get your stomach juices going, making this the perfect film to watch before going out to a meal at a Japanese meat restaurant.

Although you could certainly argue, with its ‘slice of life’ aspect, that the film follows everyday life and love and not a lot really happens, the lives of the mother, daughter and her friends are presented in a quite captivating manner, so much so that the film constantly holds the attention even when nothing much is going on. Indeed, the first hour perfectly captures the feeling of being a teenager in a small, friendly Northern Japanese coastal town. There’s a shrine where the animals (lizards, frogs – voice: Hiro Shimono) talk briefly to Kikuko, which might sound like Disney anthropomorphism at its worst, but is actually far more subtle and suggests a sort of spiritual oneness with nature. Although, equally, it might simply be Kikuko’s imagination playing out inside her head, the narrative being told from her point of view throughout.

Life, work, school, friendships, countryside, town, everything here seems related to everything else. Which context only serves to make the possibility of Nikuko’s new relationship with the food vendor, the move to a new town it’s likely to entail, and the darker, more intense flashback on which the film embarks related to all this, all the more unsettling.

In short, although the film is VERY Japanese, its context transcends that to make it highly accessible to a Western audience. Particularly, it must be said, if you’re a pre-menstrual teenage girl. Although it’s a minor element and there’s a great many other things going on, this is quite possibly the most direct engagement of the cinema with menstruation since Carrie (Brian DePalma, 1976). Unlike that film, though, it doesn’t turn having a period into tricks with buckets of blood and a bloody, avenging angel finale, opting for something much more gentle and accepting – periods (when they finally start) as part of the natural ebb and flow of the wider pattern of everyday life. It certainly had this effect on me as I watched, and I’m a middle-aged man, which suggests it has very effectively universalised its expression of this experience for audiences. If you’re feminine in gender and much younger in age, I’d imagine its impact would be magnified considerably.

Ultimately, this is sassy, languorous and highly engaging. The way it plays might be very different from anything of which you might imagine animation capable, which is no bad thing. It’s all very pleasant and sun-drenched, and it’s hard to think of a nicer way to spend a summer afternoon, unless you augment it with a trip out afterwards to a slap up, meat-based Japanese restaurant. A most satisfying if often highly unpredictable delicacy.

Fortune Favours Lady Nikuko is out in cinemas in the UK on Wednesday, August 10th.

Trailer: