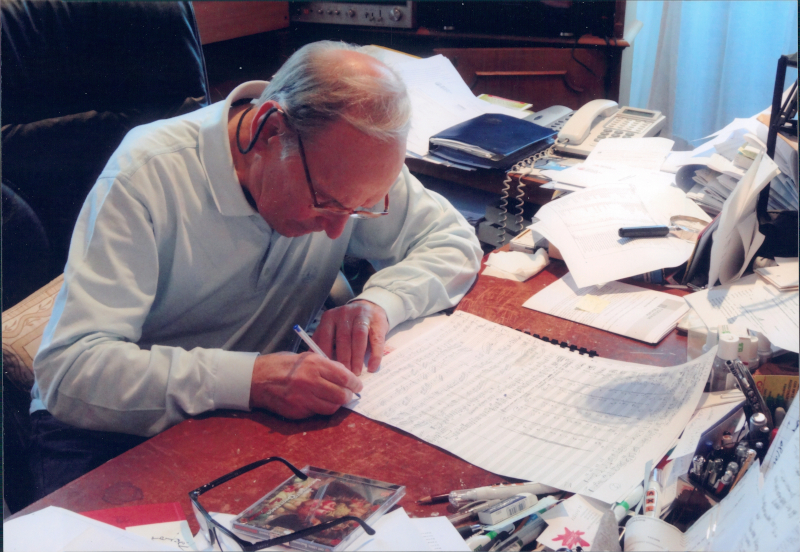

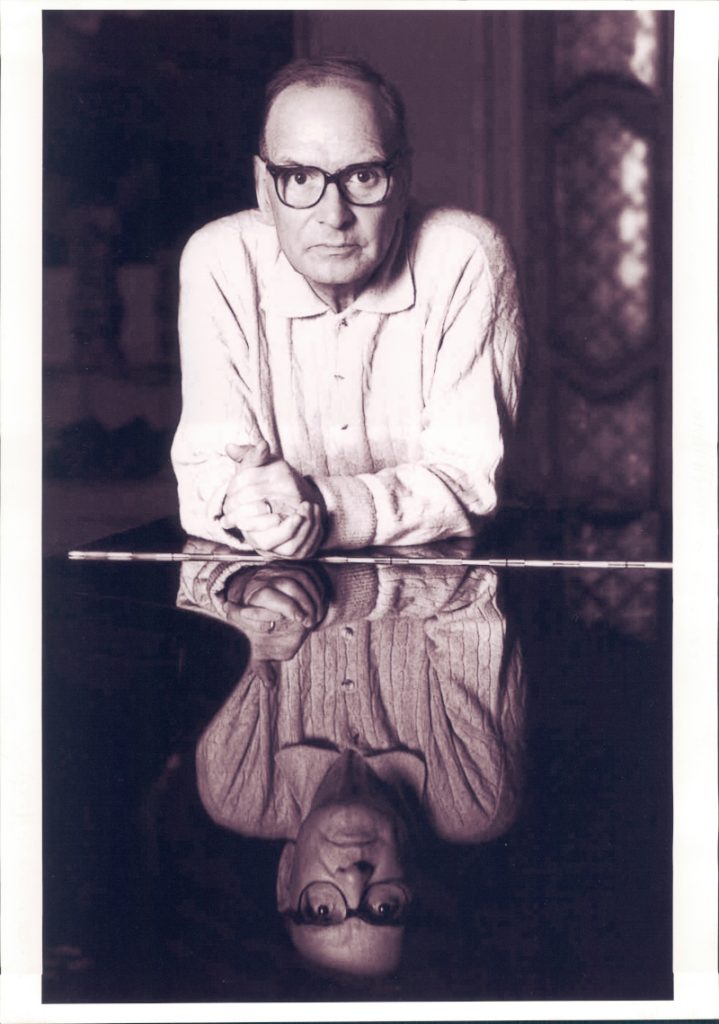

Director – Giuseppe Tornatore – 2021 – Italy – Cert. 15 – 156m

****

Documentary Ennio: The Maestro looks at the career of Italian film composer Ennio Morricone – out in cinemas on Friday, April 22nd

It’s difficult to know where to start with Ennio Morricone, whose career in film music covers some 70 years. Tornatore adopts the chronological approach, starting with his early life. The composer’s father was a trumpeter who pushed young Ennio to learn that same instrument, leading to entry into Rome’s Santa Cecilia Conservatory where he studied both trumpet and composition. His father had raised him with a strong work ethic – using the trumpet to feed your family – and much of his early work was as a trumpeter on movie soundtrack sessions, including Othello (Orson Welles, 1951).

His wife secured him a brief stint at TV channel RAI where she was working, but on being told that he wouldn’t be able to perform anything recorded there anywhere else, Morricone quit almost immediately. Inspired by seeing experimental composer John Cage perform live, he formed the Nuovo Consonanza Improvisation Group to experiment with what he called “traumatic sounds”. This approach would inform a number of his later soundtracks. He garnered something of a reputation as an innovative arranger and exponent of counterpoint in songs for popular singers. For example, the recording of Il Barattolo for RCA included the use of a tin can.

Morricone started working on film scores under a pseudonym as he didn’t really think of composing for film as real music work. Scores on early spaghetti westerns such as Gunfight In The Red Sands (1963) bought him to the attention of Sergio Leone who was making his first Western A Fistful Of Dollars (1964). Leone took him off one afternoon to see Yojimbo (Akira Kurosawa, 1961), its template.

As it turned out, Morricone recognised Leone when they met because they happened to have attended the same school together. He would go on to work on all the director’s subsequent features, mostly Westerns including two more Dollars films starring Clint Eastwood – For a Few Dollars More (1965) and The Good, The Bad And The Ugly (1966) – plus Once Upon A Time In The West (1968) and Leone’s final film, the ambitious New York gangster epic Once Upon A Time In America (1984).

His scores revolutionised the Western through their use of instruments like guitar, trumpet and Jew’s harp; techniques such as blending non-verbal, vocal performances with instruments, whistling, and deployment of non-instruments (among them, cracking whips), harking back to his Nuovo Consonanza experiments pushing the boundaries of what was possible in music.

If Leone is the director with whom Morricone is most frequently associated, he collaborated with many others both inside his Italian homeland, including Argento, Bertolucci, Cavali, Pasolini, Pasolini, Petri and Pontecorvo. and, later on in his career, internationally in Hollywood with the likes of Terrence Malick (Days Of Heaven, 1978), British director Roland Joffé (The Mission, 1986), Brian De Palma (The Untouchables, 1987), and Quentin Tarantino (The Hateful Eight, 2015).

The 1960s and 1970s were his heyday, churning out Italian soundtracks at breakneck speed, with the release of 21 movies containing his scores in 1969 cited by Giuseppe Tornatore as an example.

Morricone scored three early films for horror director Dario Argento (The Bird With The Crystal Plumage, 1970; The Cat O’ Nine Tails, 1971; Four Flies On Grey Velvet, 1971) until his producer father Salvatore Argento clamped down on the grounds that Morricone was repeating himself. The composer doesn’t see it like that, regarding the films as very different, although they all deal in unsettling sounds coming out of his Nuovo Consonanza work. (Curiously, the documentary fails to note that Argento supplied Leone with the story for Once Upon A Time In The West).

He worked with sometime documentarians Gillo Pontecorvo (The Battle Of Algiers, 1966; Burn! / ¡Queimada!, 1969) and Liliana Cavali (The Year Of The Cannibals / I Cannibali, 1970) There was some dispute with both directors wanting the same piece of his music for both ¡Queimada! and I Cannibali, with variations of a piece originally composed for the latterending up in both.

He would fight with directors who asked him to copy an existing piece of music rather than create something original that suited the scene as Pier Paolo Pasolini did for The Hawks And The Sparrows (1966) when the director already had a pile of records lined up for different scenes.

For Elio Petri’s A Quiet Place In The Country (1968), Morricone called in Nuovo Consonanza to provide musique concrète for images of a painter’s deranged dreams, strange noises to accompany images of toppling tables spilling paint. Despite critical acclaim, the film flopped and Morricone felt responsible.

Yet, this didn’t stop him experimenting further with sound effect equivalents in the intensely visual, non-dialogue opening of Leone’s Once Upon A Time In The West. Having previously warned Morricone that he never worked with the same composer twice, Petri then worked with him on subsequent films. For Investigation Of A Citizen Above Suspicion (Elio Petri, 1970) he created a little arpeggio theme. Petri called him in for a screening during mixing having replaced the music with parts of the score from an old Morricone gangster movie score the composer didn’t care for. Nevertheless, Petri ultimately used Morricone’s extraordinary arpeggio theme.

It’s inevitable that this documentary’s director Tornatore would talk about his own collaborations with Morricone, notably Cinema Paradiso (1988). Its themes of childhood and cinema marked it out as different from anything Morricone had done previously, and he had to be coaxed into doing it. He also includes his later Legend Of 1900 (1998).

Tornatore has conducted some remarkable interview footage with the maestro along with many of his collaborators – Clint Eastwood commenting that the music made him look great at the start of his career, Joan Baez talking about recording a vocal for a song for Sacco & Vanzetti (Giuliano Montaldo, 1971) on which the orchestra was added afterwards. There is further interview material with numerous collaborators including directors, producers, the odd critic, and musicians including Bruce Springsteen. Tornatore references HM band Metallica who open their sets with a Morricone track, although sadly he omits lesser-known guitarist Glenn Phillips’ obvious homage I’ve Got A Bullet With Your Name On It.

For me, the other two big omissions were my favourite Morricone score, the one he wrote for cops and mafia movie The Escort / La Scorta (Ricki Tognazzi, 1993) and the excerpt that I use as a demo when buying A/V equipment, the opening of his score for The Thing (John Carpenter, 1982).

However, Tornatore does manage to source astonishing RAI footage of Edda Dell’Orso singing the wordless vocal of Once Upon A Time In The West, not to mention equally compelling footage of some of the RCA songs (and their singers) on which Morricone arranged.

And although he goes into quite a lot of detail about certain of the Hollywood movies – Once Upon A Time In America, The Mission, The Untouchables, The Hateful Eight – I personally found the earlier material on the Italian movies and music business, and Morricone’s education and upbringing, far more compelling.

To the viewer aware of a smattering of this prolific composer’s astonishing body of work, this is a most welcome overview likely to introduce you to unfamiliar films and scores and, perhaps more significantly, provide a helpful framework through which to explore the wider body of work of one of the cinema’s truly great composers.

And if, like me, you go back to listen to any Morricone recordings you own after seeing the film, you may well find you understand them that little bit more as a direct result of viewing.

Ennio: The Maestro is out in cinemas in the UK on Friday, April 22nd.

Trailer: