Director – Alfred Hitchcock – 1960 – US – Cert. 15 – 109 m

*****

A woman steals some money she’s supposed to bank at work and leaves town, winding up at a motel off the highway… where terrible events ensue – back out in cinemas on Friday, May 27th

(Warning: may contain spoilers.)

Often imitated, never equalled, Psycho sits so large in the firmament of cinema that it’s impossible to write about it as if seeing it for the first time. Hitchcock reused to admit cinemagoers after the film had started – a radical idea in a time when punters would show up, go in, watch ’til the end, watch from the point where they came in, then leave. “We won’t allow you to cheat yourself” ran the foyer blurb agreed between Hitch and Universal.

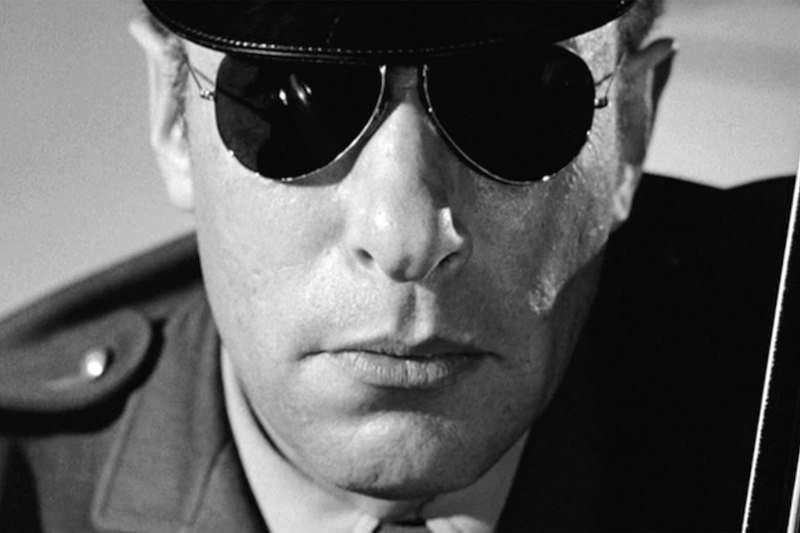

By the time I first saw the film, twenty years after its initial release on a BBC TV rerun some time in the late seventies / early eighties, I had seen clips of various scenes, probably in a BBC documentary about Hitchcock. Definitely the notorious shower scene. Probably the patrol man. Probably the staircase murder. Probably the skull lit by the swinging light bulb. Probably Norman as Mother saying, “she wouldn’t even harm a fly” with the briefest of lap dissolves to the human skull.

What first reeled me in, in a pre-video era, British world where access to movies was largely through TV broadcast and TV documentaries about them, was the shot of a woman’s naked legs lying in a bath, the camera following blood and water trickling down into a plughole, then the shot pulling out in a spiral from the dead Janet Leigh’s eye. Hollywood stars are mortal, like the rest of us, even if their images live on in celluloid, computer file and cultural memory. Later, I would identify the flow of blood with the idea / image of a woman’s period, something indicative of not only mortality but also life and being.

All Hitch did in the jocular trailer (below), which I only came across some years after first seeing the film in its entirety, was show a woman screaming in the shower at the end. That wasn’t even from the film (it’s actually Vera Miles, who plays the sister of Marion Crane, played by Janet Leigh). The trailer consists of walking round the set of the motel and the house where the murders took place. Hitchcock brilliantly talks about each incident in the film, but abandons sentences part-way through with a wave of his hand before actually telling us anything. So even before the first audiences saw the film, they felt like they’d seen the film. Although, apart from a woman screaming in the shower, the trailer no more than hints at the various shock scenes awaiting the (sort of) unwitting audience. You’re warned of what’s coming but then you’re not warned exactly what’s coming at all.

Warning but not warning exactly. The opening shots promise cinematic bravura to come: Wide establishing panning cityscapes (one dissolving into another), the second zooming towards (cut) craning down to an open apartment building window (cut) going in through the window to see Sam (John Gavin) standing naked from the waist up and Marion (Janet Leigh) lying on the bed in virginal white bra and slip, a visual presentation of a woman unheard of on the mainstream Hollywood cinema screen in 1960.

But even before this, the black and white, Saul Bass’ titles with the words flying in and out horizontally and occasionally vertically, the lone, major talent names split into three horizontal sections pulling in opposite directions, suggesting the pulling together then rending asunder of various major collaborators in the film-making process – cast, composer, director, gives a hint of what is to come. So too from the outset does Bernard Herrmann’s bravura score, composed and played by stringed instruments only, deeply unsettling and violent. The only comparable score I can think of is Howard Shore’s for Crash (David Cronenberg, 1996) which is put together with nothing but electric guitars.

Much of the film is, to all intents and purposes, silent cinema (Hitch’s British career harks back to the silent era of the 1920s) accompanied by Bernard Herrmann’s bravura score (stringed instruments only, deeply unsettling). Hitch planned and shot the notorious shower sequence without music. Herrmann presented him with music for it anyway, music which suggests slashing, shrieking and, significantly, birds screeching. (The role of birds in Hitchcock’s prior body of work, where they frequently appear as agents of chaos, is a rewarding field of study in itself. His next film, The Birds/1963 foregrounds this element.)

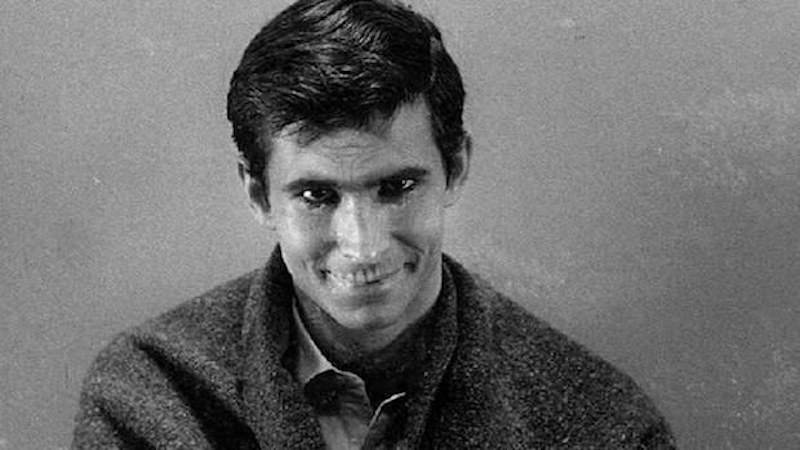

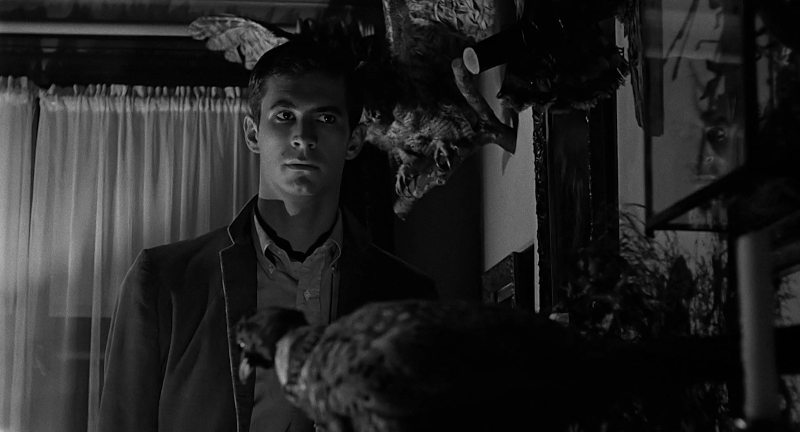

Motel owner Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) has stuffed birds in his parlour behind the office, where he feeds (stuffs) Marion, whose surname is Crane, a bird that takes flight. But I digress. Something it’s easy to do with a film so rich and strange. (One of Hitch’s early talkies, incidentally, was Rich And Strange (1931), named after a line in Shakespeare’s play The Tempest.)

So what will I make of the film now, sitting down to watch it for the umpteenth time? On this occasion, I find the opening two scenes with actors (the hotel room tryst, after the titles and bravura city to window to interior / bra and slip opening, and the scene at Marion’s office with fellow worker played by the director’s daughter Pat plus her boss and his client) somewhat stagey, even though these introduce a lot of important themes (not to mention Hitch’s brief cameo) and provide Marion’s character with a bundle of money which isn’t hers, setting up the ‘woman on the run with stolen money’ scenario which forms the first half of the film. I’ve never had this reaction to these two scenes before, and perhaps next time I watch the film (because it is a film to which to return over and over through the years) I won’t feel that way about them. But it’s how I reacted this time.

After those two scenes, though, as anticipated by those titles, you’re watching a woman who makes a bad decision being pulled apart before pulling herself back together again. Then being pulled apart by unexpected forces beyond her control. With Marion / Leigh gone, the remainder of the film switches between motel owner Norman / Perkins, and investigations into the motel and house first by private detective Arbogast (Martin Balsam) then by Marion’s sister Lila (Vera Miles) and Sam. There is also a little coda explaining what we’ve seen by a psychiatrist (Simon Oakland) who clarifies exactly what has been going on with Norman and Mother and a final shot of Marion’s car being pulled out of the swamp where Norman had previously sunk it with her body and personal effects, including the money of which he’s unaware, inside.

Janet Leigh’s performance when she’s sitting in the car driving, through the day and through the night, remains extraordinary, a woman torturing herself as to what she’s done and what she’s going to do. There are other things going on outside of the actress’ contribution. The moment the first drop of rain hits the windshield as she drives into a thunderstorm always feels to me like she’s crossing the boundary into the land of Hell. Her scene with a suspicious highway patrol officer (a terrifying Mort Mills) who in broad daylight finds her sleeping in her car by the side of the road remains as effective as when I first saw it, probably as a standalone clip.

After Marion’s departure, the fascinating Norman Bates (the film’s other magnificent performance) and his mother hold our interest. And after the shower scene, the film still has some further shock scenes to deliver. In terms of warning but not warning exactly, the scene where Arbogast climbs the stairs in search of Mrs. Bates contains a delicious close up shot of the bottom of a door opening slowly admitting light, telling us something is about to happen. (The shot owes much to a similar moment in French thriller Les Diaboliques, Henri-Georges Clouzot, 1955.)

For more on Psycho, read my review of the excellent documentary 78/52 (Alexandre O. Philippe, 2017).

Psycho is back out in cinemas in the UK on Friday, May 27th.

Trailer (1960):

How Hitchcock Got People To See Psycho:

Trailer (2022):