An introduction to the films of Korea’s late and, lamentably, largely unknown director Kim Ki‑young – originally published in Manga Max, Number 8, July 1999. Reprinted here to coincide with London East Asia Film Festival (LEAFF)’s screening of Woman of Fire (1971) on Friday, October 29th. If you missed it, the restoration screens again on Friday, November 5th as part of a strand dedicated to actress Youn Yuh-jung at London Korean Film Festival (LKFF) which runs from Thursday, November 4th to Friday, November 19th

It seems unthinkable that the world could have failed to recognise a director whose 2.35:1 widescreen visuals compare favourably with Seijun Suzuki and John Boorman and whose marriage of technique with subject matter is as terrifying as anything by Dario Argento or Alfred Hitchcock. Nevertheless, when 1997’s Pusan International Film Festival (PIFF) ran a retrospective season of films by Kim Ki-young (the first of a proposed series of annual events showcasing Korean directors) it quickly became clear to astonished audiences that the unthinkable had indeed happened. Sadly, on February 4th 1998 – within six months of his new-found international acclaim – Kim and his wife died in a fire in Korean capital Seoul. Some months later, six of the films made their first UK appearance at 1998’s inaugural Pan Asian Film Festival where they again astounded audiences. PIFF subsequently and posthumously discovered Kim’s final feature A Moment To Die For (1988) which concerns a tangled relationship between an insurance salesman, his wife and a sex-crazed woman – and the type of trademark grotesque depiction of sex and death fantasies for which the director is becoming internationally known.

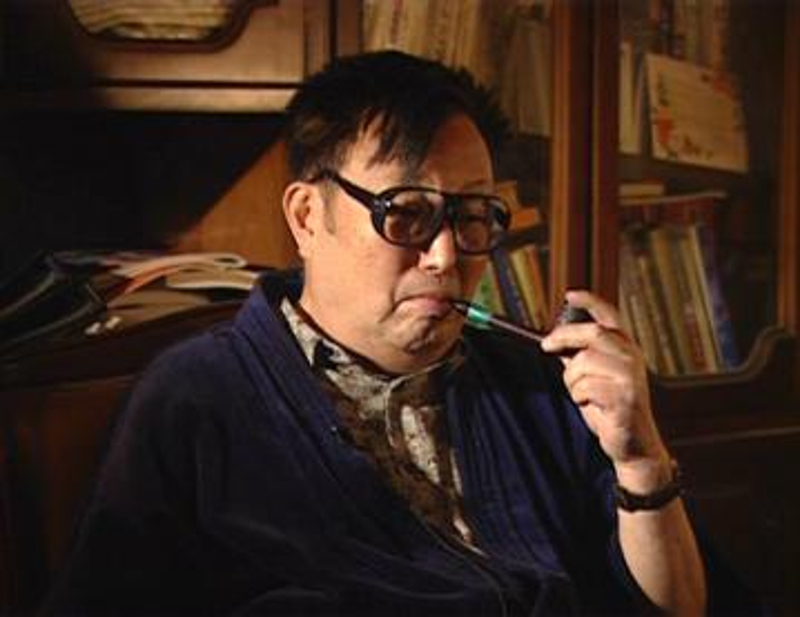

Kim Ki-young was born in Seoul (his ancestral hometown) in 1919 but spent his secondary school years in Pyongyang where he won prizes in the fine arts and poetry. After failing the entrance exam for Severance medical school in 1940, he bummed around Japan for three years on the breadline, watching movies in Tokyo (Ben‑Hur, Genghis Khan, M) and theatre plays wherever he could. From 1946 he returned to Korea and directed theatre plays as a sideline while attending dental school, then entered the country’s film industry around the time of the Korean War, directing the first of his over thirty films in 1955. Initially, he made his name directing historical dramas and melodramas (such as Yang San Do/1955 which features a love triangle plot), finessing his reputation with the urban jungle realism of his acclaimed Resistance Of Teenagers (1959). But then in his ninth film, acceptable social realism gave way to something altogether different.

FIRE WOMEN

According to Kim Ki-young, The Housemaid (1960) “was released amidst a rising social controversy over problems cropping up over the employment of housemaids.” Its move into neo-noir territory proved something of a departure for both Kim and Korean cinema. When a factory girl is sacked for sending a love note to the company’s respectably married (with two children) music teacher, she returns to the countryside while her best friend (on whose behalf she really wrote the note) becomes the teacher’s star pupil who recommends a sluttish, smoking workmate to start work as the piano teacher’s housemaid upon his family’s move to a larger house.

Unaware of his pupil’s crush, the teacher allows his seduction by the maid who then insists herself his mistress. The stage is set for the nuclear family to be torn apart by desire, deception and rat poison. The ending (skip remainder of this sentence if you don’t want to know) culminates in a double suicide by maid and husband.

A BARRAGE OF CLOCKS

The narrative’s shift of focus to each one of three women in turn is an archetypal Kim touch. Some specific elements survive into its second remake Woman of Fire ’82 (1982) – a wife who earns a living while her husband produces a meagre income, an upstairs piano room, an insistent ticking rhythm on the soundtrack (here the wife’s sewing machine, in 1982 a barrage of clocks), a number of sequences involving rat poison and a finale wherein the collapsed poisoned maid clings to the leg of the poisoned husband as he staggers downstairs, bashing her head against each step as he descends.

But whereas Kim’s later films portray men as pathetic creatures lacking sexual self-control who are completely at the mercy of the women around them, his leading man here is so upright and morally concerned as to appear unconvincing when seduced. The genteel portrayal of the wife likewise misses the mark. But the maid, snatching a live rat by the tail from a kitchen cupboard, slithering seductively round the husband’s foot or appearing as a terrifying apparition in the rain outside the piano room window completely nails the part on a par with Kim’s later, equally horrifying female characterisations.

SUICIDE PACT

Clearly, the subject matter of The Housemaid was extremely personal – Kim remade the film twice as Woman of Fire (1971) and the aforementioned Woman Of Fire ’82. The 1971 reworking shifts the familial home into a house attached to a poultry farm where the housemaid becomes pregnant by the head of the household, kills his wife’s baby and ultimately talks the husband into committing double suicide.

1982’s second reworking retains the above changes. It opens with a characteristic Kim shift in emphasis from one character to another then another – the musician’s wife is concerned about his growing attraction for his red‑dressed student and admonishes her new, country-bred housemaid to protect her husband (and the family unit) at all costs. When the wife (who runs the farm) goes away on business, the student comes on to the inebriated and sexually aroused musician who looks set to succumb until the horrified maid sees the student off the premises. The drunk then mistakes the maid for his lover and rapes her, making her subsequently demand to be treated as his mistress. No matter how demented and extreme her subsequent actions, the maid’s motive is now that of the innocent wronged which renders the subsequent playing out of emotional extremes all the more poignant (not to mention effective).

DON’T DRINK THE WATER

The 1982 version’s performances are far more polished – the shrewd businesswoman wife is now earthy and passionate…and increasingly forsaken, her hapless husband a pathetic creature subject to the whims of the two women in their ever increasing enmity. Little sequences survive from The Housemaid rendered far more effective by embellishment – the sequence where the household’s young son drinks the poisoned water, for instance, adds additional prior dialogue whereby the boy is worried that the water is poisoned and asks the maid to drink it. Then, as before, she drinks, hands it to him, he drinks, he hands back the empty glass and she regurgitates the mouthful of poisoned water. The use of scope (the 1960 version is shot 4:3 Academy ratio) is impressive too, most notably in the maid/husband sex scenes in the piano room where one wall is now covered with his cherished collection of ticking clocks (replacing the original’s sewing machine rhythm) which almost seem to control the rising tide of sexual turmoil sweeping through the household. The finale, in which the poisoned maid clings to the poisoned husband’s feet so that her own head thumps loudly against each step of the staircase as he descends is likewise as numbingly effective: the same scene in the 1960 original, though undoubtedly powerful in its day, seems laughable by comparison.

RATS IN MY KITCHEN

The Insect Woman (1972, available for free on the Korean Film Archive YouTube Channel, later remade by Kim as Carnivore / 1984) likewise features weak‑willed men unable to control their sexual appetites and two female archetypes recurrent in the director’s most personal films – the innocent raped by a man who subsequently forces herself on him as all-consuming mistress and the wife fighting to preserve the family unit in the face of her husband’s adultery. The raped innocent has a prostitute’s madam as a confidante – because of whom the rape (by one of the madam’s clients) occurs in the first place. His wife strikes a deal with the self-styled mistress – the latter can have the husband for afternoons and evenings – provided he always returns to the wife after midnight.

Tensions are further compounded by the wife’s having a vasectomy performed on the husband to prevent the mistress bearing his children, followed by the appearance in the mistress’ house of a baby which later turns up as a corpse in the fridge. The family’s legitimate daughter, meanwhile, plays piano to rats in a jar to make them dance; similar looking rats start to infest the mistress’ flat. As ever, Kim is thoroughly at home with the scope format, exploiting it with skill comparable to such masters as Boorman or Suzuki.

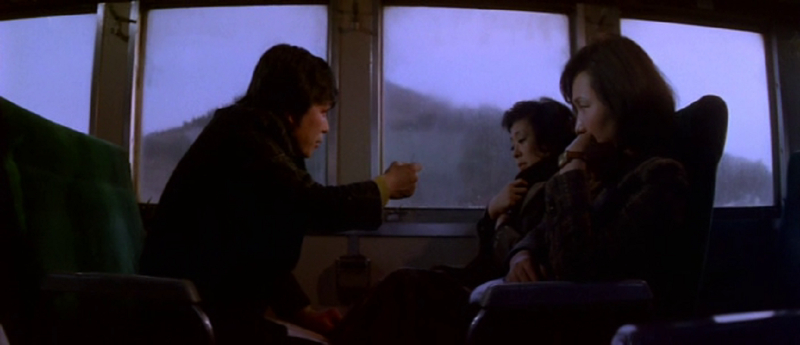

STRANGERS ON A TRAIN

Hitchcock once commented on his films that it was amazing how a director could remake the same story over and over throughout his career. But Promise of the Flesh (1975) certainly breaks the domestic horror mould discussed thus far. Indeed, it’s a unique film in director Kim’s singularly personal canon never mind the annals of cinema. A woman takes a train from the big city out to her mother’s grave by the sea…in the company of a woman prison officer. The man sleeping under a newspaper on the two seats opposite them tries to strike up a conversation, none too successfully. The first woman contemplates murder.

When the train reaches its destination, the woman visits the grave then waits for the man on a bench…she’s two hours before the time they agreed, he turns up in the dark, three hours late, having failed to collect some money he was owed, killed a cabbie and become a fugitive from the law. Two detectives shadow him on the return train and after discussing the situation with the lady warder allow the pair to consummate their relationship in a neighbouring stationery carriage when the train makes an unscheduled stop. The whole thing is considerably less linear and more complicated than that, but the above conveys the rough idea. As a portrait of freedom and entrapment as related to the two lovers, it’s highly compelling, albeit bleak in the extreme. Kim, master director that he is, never misses a trick: as love stories go, this one is seriously deranged.

PIPE DREAMS

More bizarre still is Ieoh Island / Iodo (1977). A man implicated in murder visits the island birthplace of his alleged victim. The place is populated largely by native women divers who believe that men living on the island will be taken from them by the sea demon. They also believe in a mythical island named Iodo which may or may not be real. The supposed murderer questions various women who relate stories about the victim who tried to set up a seafood business which failed because of sea pollution and found himself sold via business debts he couldn’t meet into living with a mysterious, veiled, rich older woman.

While many of Kim’s films shoehorn into the crime genre without too much difficulty, this one treads more of a balance between the crime and arthouse genres, slipping ultimately towards the latter. Extended sequences of open air island ritual ceremony are followed by an extraordinary sequence (apparently missing from some prints, although present in the one screened in the UK in 1998) in which a woman claims the seed of a freshly drowned man by inserting a pipe down his penis to stiffen it and then participating in necrophilia with his inanimate corpse with the approval of the local (female) shamen.

DEATHS OF A SALESMAN

If director Kim’s more personal works justify the auteur tag, Killer Butterfly (made in 1978 from neither his own script nor one he had any apparent desire to shoot) doesn’t really fit that argument. Nevertheless, it’s a terrific piece of genre cinema not unlike a Tsui Hark supernatural outing which opens with a man chasing butterflies in a park who suddenly meets a beautiful woman intent on killing herself and taking her with him as a double suicide.

Although he survives, he lacks the will to live but is prevented from killing himself by a vendor of a book about The Will To Live who he can’t get rid of no matter how hard he tries – he buries him, he burns him alive…the man just keeps coming back, even as a skeleton. Then he gets involved with another woman, whose butterfly pendant resembles the one the police gave him off the dead woman of whom the second woman was the friend sworn to double suicide. It may not be the director’s personal favourite – indeed he disowned it in interviews – but it remains an impressive and powerful piece nonetheless.

The European Premiere of the brand new 4K restoration of Woman of Fire plays in plays in LEAFF, the London East Asia Film Festival, in the Retrospective section on Friday October 29.

If you missed it, the restoration screens again on Friday, November 5th as part of a strand dedicated to actress Youn Yuh-jung at LKFF, the London Korean Film Festival which runs from Thursday, November 4th to Friday, November 19th.

A slightly shorter version of this article was originally published in Manga Max, Number 8, July 1999, to coincide with that year’s London Pan-Asian Film Festival.

Trailer (The Housemaid – French subtitles):

Trailer (Woman Of Fire):

London East Asia Film Festival (LEAFF) programme (please click links):

Official Selection, Competition, Hong Kong Focus, Documentary, Retrospective,

For more about Kim Ki-young, click the Kim Ki-young tag in the list below: