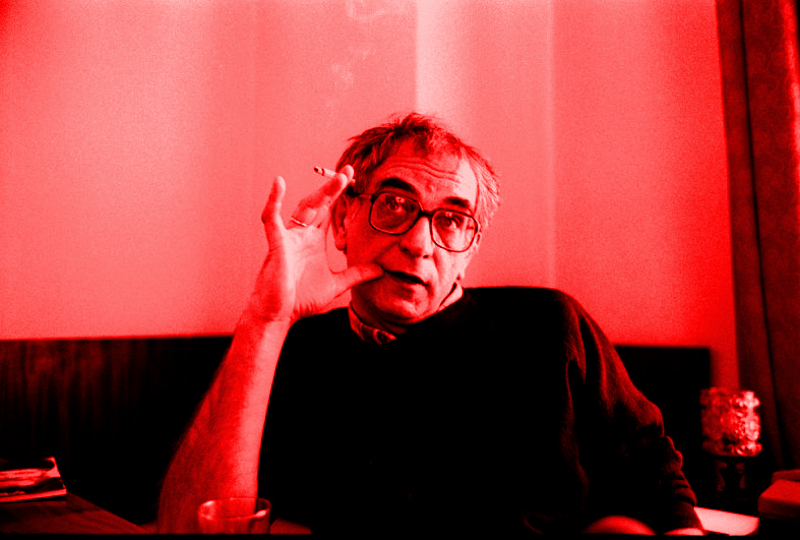

Transcript of interview from 1994 when Kieślowski was promoting Three Colours: Red. At the time, the other two films in the trilogy had by then been screened to press.

You intend to make no more films after Red. So what do you plan to do now?

“I want to live.”

What about artistic – or other – work of any sort?

“No, I can’t say.”

When we spoke about Blue, you told me how in many ways you found literature more interesting than film making. We discussed Blind Chance in terms of the conditional imperfect tense. Red seems similar out of the whole body of his work – closer to Blind Chance than anything else.

“Yes, maybe, in a certain general way of thinking, in construction.”

Not in the sense of three parallel “what if?”s, but more – if one comes at Red from a literary perspective – as a conditional tense.

“No, I don’t think it’s conditional. In fact I think it would be quite difficult to find a literary explanation there. That sort of thing I think has been tried out and discovered by the cinema rather than literature. Of course, it has been used in literature, but it’s a very much more suited to film than it is to fiction. Here there was a challenge to make something that doesn’t happen in the past but is actually happening in the present. This for me was like a challenge in a certain language.”

So these two people who haven’t so far met…

“These are people who are missing each other in space rather than in time. But as far as language is concerned, I have in mind the present retrospection. What you’re talking about is people missing each other in time – which did interest me as well. Or you could say that the whole train of thought is retrospection. It’s all retrospection, everything that happens to Auguste. It could have happened forty years ago, but I tried to make it so that it’s happening now, and it just repeats the fate of the judge. That’s what I call a present retrospection. Should I explain this a bit more clearly?”

I encourage him.

“Well, we have a story that is happening in the present where a judge meets a woman. I imagine that everything that the judge is saying which is very straightforward in the film but we showed all in retrospective, we showed it in the past. But rather than showing it all happening in the past, it’s all happening in the present, transposed there by forty years.”

“Now, whether it happens to someone who’s very similar to the judge – whose fate is very similar and whose profession’s very similar – or whether it’s just another possibility of his own fate had he been born forty years later – we don’t know that. It’s possible to interpret the film several different ways.”

Was he inspired to create – write – Red primarily because of the character of the judge rather than the other way round?

“The meeting of the two characters was interesting as well as the individual characters themselves.”

The meeting of the two characters and the non-meeting of various others too.

“It’s like we can’t go back to the past. Everything that’s happened has happened. All the foolish things he’s done will stay foolish things. All the mistakes will remain mistakes. You can’t change anything. But in the cinema you can. In the film, you can imagine that many people manage without making any errors – or making other errors.”

“In fact, in the film, the judge can repeat his life and meet the right woman, whereas in real life he doesn’t. Perhaps in real life he hasn’t noticed her, but maybe she was right next to him but he never noticed her. Now he’s repeating his life, he will notice her because he knows how important it is. That might completely change his life, this view of the world.”

This sounds very similar to Blind Chance where we started.

“Yes, but here it’s a question of time.”

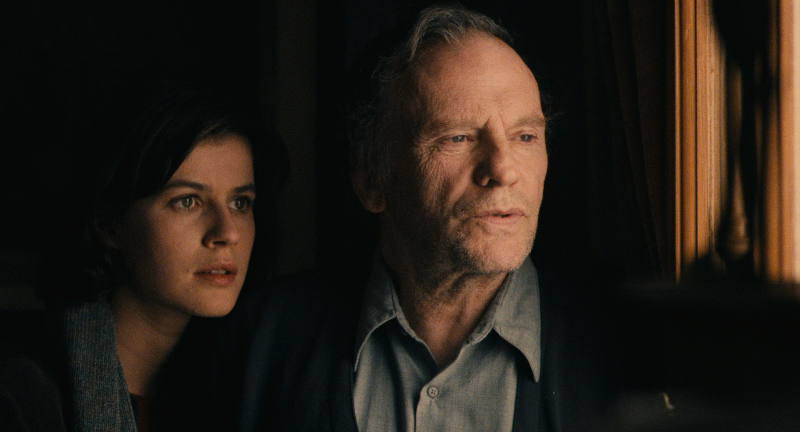

When Kieślowski first approached Jean-Louis Trintignant, the actor put the director onto another actor who he thought would be better – but who, as it turned out, had just died. Before discovering this person’s death, did the director see any of his work?

“No, I don’t know him at all. I wasn’t interested in anyone else as soon as I met Trintignant.”

What were the qualities that he saw in the actor that made him right for the part?

“I just think he is like that in reality.”

Had you met him before?

“No, I hadn’t, because he hasn’t made any films for a long time. I just couldn’t find any other actor who was close to that part – there wasn’t one like that. I started looking in the past at actors that used to work but is now somewhere at the side. And I thought about him. I used to like him a lot. He’s changed a lot – in a direction that’s very close to the character of the judge. I think he’s quite a (misanthrope) people hater.”

Eavesdropping on people’s telephone calls is both fascinating and compelling.

“Well, evil is hypnotic.”

It’s one of those actions that, as you watch it, you disapprove but at the same time are fascinated by it. It didn’t seem wholly bad, somehow – which may be what he’s saying.

“I think this this is what the character is about, that there is this sort of ambiguity within him; that he can play somebody who is evil and yet deep inside, you can feel there’s someone very human. Although he doesn’t show it externally.”

Evil isn’t a word I would use to describe the character. Human is closer. Misguided perhaps.

“He’s so unsympathetic in the beginning, in the way he abuses the girl in the beginning and brings her down. He’s not a nice guy.”

How fascinated is he by high up characters (such as judges) and their capability for evil even though they’re supposed to be meeting out the law.

“I can’t say that particularly fascinates me, but a person who judges does fascinate me. A professional judge, a person who decides the fate of other people.”

How about the characters of the girl and her boyfriend and you never ever see. Where did those characters come from? Inspired by people he’s met, perhaps?

“Of course they’re based on all sorts of people but it’s difficult for me to say where they actually sprang up from. There’s no doubt that that personality reflects the private person of the actress – because she is that sort of person. If I didn’t know her, I’m not sure I would have invented such a role. It’s a very difficult to role to think up and to get somebody good to play. It’s really easy to play someone who’s good. That’s really difficult. It’s easy to play someone who’s good, but to make it appear real or credible is far more difficult.”

It’s much easier to portray evil than good.

“Yes, of course, it is much easier.”

ENDS.