Director – Coralie Fargeat – 2024 – US – Cert. 18 – 140m

****1/2

Hollywood star Elisabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore) hosts a network TV keep fit show, but she’s getting on in years – and so is her audience. The show’s producer Harvey (Dennis Quaid) has decided that younger talent is needed in order to attract a younger audience, and gives her the elbow. By a quirk of fate or screenplay, a mailshot about something called The Substance arrives in her penthouse apartment. It’s some sort of beauty product, although the high-end design of the blurb doesn’t explain exactly what it is or what it does. There’s a phone number.

Elizabeth’s identity is bound up with the former show. She calls the number. She engages in conversation with the unseen voice on the other end of the phone. She decides to give The Substance a try. She is told to write down an address. Later, she is sent locker card key number 503 and instructed to collect her package from that address. It turns out to be a derelict entrance with a shutter that only opens part way to about a yard in height, meaning you have to duck under it.

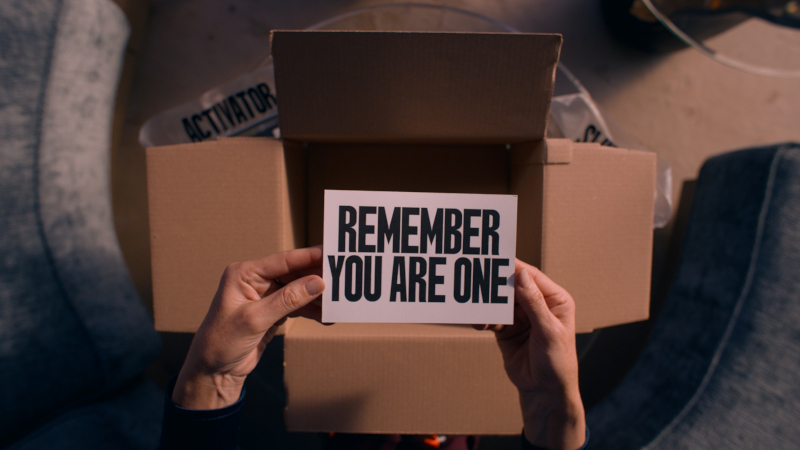

Inside, it looks like an abandoned, narrow corridor, at the end of which she finds a gleaming, pristine white room with lockers. Sure enough, her cardboard box is waiting in locker 503. She carries her box home, opens it up and studies the highly cryptic instructions.

These instructions include “you are one” and “you must switch every seven days, no exceptions”. The product has three constituent parts: Activator, Stabiliser and Food Packs. So she takes it into her bathroom and injects herself with the Activator (instructions: to be used only once). She collapses, her back splits open. Out of her body emerges the new, younger, fitter her (Margaret Qualley from Once Upon A Time… in Hollywood, Quentin Tarantino, 2019; Kinds of Kindness, Yorgos Lanthimos, 2024), who sews the back of her old self back up and plugs in the Food Pack, which supplies liquid food to the first body through a tube. The new, younger, fitter her must use the Stabiliser once every 24 hours.

The new, younger, fitter her responds to the ad for her old job with Harvey and gets it, negotiating in the process that she has to be away every other week caring for her sick relative. She christens herself Sue and becomes a huge success. So far, so good.

What’s compelling here is the question of, what exactly is The Substance, and how does it work? It’s compelling in the same way as (although very different from) the life cycle of the alien in Alien (Ridley Scott, 1979). It’s something with which, the first time we see the film, we’re unfamiliar, and no matter how awful it might turn out to be, we want to know how it develops through all its various stages. Once you’ve seen the film, you might, again like Alien, want to return, and revisit that, over the years.

A high ‘ick’ factor in the transformation sequences owes much to the signature films of body horror pioneer David Cronenberg. And there’s a great deal of physical energy in the network TV synchronised workout sequences with both the older and younger versions of the protagonist, although the live social media workouts in Sweat, Magnus von Horn, 2020) did it all first.

There’s also a “take your medicine and use it properly… or else” feel, as our heroine injects herself with the 24-hour Stabiliser to stop herself feeling faint or woozy.

The Substance, it may be noted, comes in boxes. And as the voice on the other end of the phone repeatedly points out, once the box has been opened, there’s no going back. The problem is that The Substance requires its users to follow instructions. And people are notoriously bad at doing that.

The washed-up Elizabeth starts using it in the first place because of an inability to accept her lot. After running into an old classmate from school days, simultaneously at ease with her and starstruck, she calls him up for a date, yet later finds herself unable to meet him as agreed.

The rejuvenated Sue, on the other hand, seems to have no such scruples, bringing young men back to the apartment, which gets in the way of her switching back to Elizabeth’s body after seven days.

The process starts aging the dormant Elizabeth, who wakes first with one finger considerably aged and later on as a wizened figure with a fingernail falling off (all reminiscent of Cronenberg’s The Fly, 1985). This process accelerates the greedier Sue gets, with the final half hour switching to queasily funny, black comedy gross-out in the manner of Society (Brian Yuzna, 1989) as Elizabeth / Sue become fused in an amorphous mass just in time for Sue’s upcoming New Year’s network special.

Fargeat excels at both casting and getting good performances from her cast. It’s imperative you believe Qualley to be a younger version of Moore, and that works admirably. Both actresses are striking. Moore becomes increasing desperate as she ages and is covered in ever more complex prosthetics make-up; the deceptively innocent-looking Qualley is unable to prevent herself from getting greedier and greedier, extending the time she spends in her body over and above its seven-day allocation.

Quaid, meanwhile, makes a suitably at once respectable and sleazy producer, protesting his love for his wife (who we never see) even as he boots the aging Moore off the airwaves to replace her with a younger model. Fargeat has a lot of fun in the scene where he talks to Qualley in a restaurant while stuffing his mouth noisily with prawns.

As with Fargeat’s earlier Revenge (2017), she adroitly choreographs the slippery, unbalanced mayhem but perhaps leans a little too heavily on genre tropes. A scene underscored by bits of Bernard Herrmann’s score for Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, 1958) pilfers the image of one person dragging another so that their feet bump over a series of steps.

Then there is the pristine locker room, with lockers on the wall in an arrangement reminiscent of a rectangular grid, which to this writer conjured up the similarly clinical rooms in which the astronaut finds himself at the end of 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968). Which means that when Elizabeth steps out of the grotty, derelict corridor into this room, it’s as if she has left the decaying hulk of the boat at the end of Videodrome (David Cronenberg, 1983) for 2001’s pristine, closing set. Which is, to say the least, extremely weird. There is also a lengthy orange corridor leading to producer Quaid’s office with a repeating pattern, orange / red carpet that recalls the one in The Shining (Kubrick, 1980).

As mentioned earlier, the major source for the transformation sequences is the signature films of body horror pioneer David Cronenberg, with the fallen split back Elizabeth and emerging new version Sue recalling the collapsed, accelerated cancer victim of Videodrome, the “insect politics” aesthetic of The Fly (David Cronenberg, 1985) and the sequence where a character sloughs off their skin to reveal a new self at the end of Naked Lunch (David Cronenberg, 1991). Physical elements move under the body’s skin, reminiscent of those in Shivers (David Cronenberg, 1977). At one point, Moore dons a red dress and looks like a dead ringer for Debbie Harry in Videodrome. A gratuitous exploding head is lifted wholesale from Scanners (David Cronenberg, 1980). These images are absolutely integral to the Cronenberg films in which they appear; however, in The Substance, while they undeniably do the job they’re intended to do, they feel like they’ve been imported into a much more cynical, designer product of a movie to be bolted onto its insides.

If the body horror effects are familiar to those well versed in that sub-genre, the piece is more impressive where it doesn’t borrow from other movies but instead tries for something original. The graphic design of The Substance’s packaging recalls the Google web browser in its simplicity: basic lettering on reverse background. It’s not something we’ve seen repurposed for the movies before. This carries over into what The Substance is and what exactly it does.

And yet, the core of the film, made by a woman and with a central female protagonist (or one female split into two, if you prefer), is all about the female experience of being required to look beautiful, and being considered past it beyond a certain age. All these nods to Cronenberg and others work against the film’s overall purpose, to talk about the way Western society currently treats (and gainfully exploits) female body image. It’s like watching someone attempt to make a serious point but get sidetracked into imitating their heroes. Like Revenge, it’s arguably more effective as an audience-pleaser than as the feminist tract it so desperately wants to be.

Fargeat isn’t afraid of gore or special effects, and she knows how to put a narrative together. Much as I admire most of the films she references, the essence of what The Substance is about ought to be strong enough in its own right to not warrant such detours. These misgivings notwithstanding, it’s a striking piece of work and well worth your time, even if it does seem a little overlong at well over two hours. A well known advertising slogan sums it up perfectly: soft, strong, and very long.

The Substance is out in cinemas in the UK on Friday, September 20th.

Trailer: