Directors – Sidney Lumet, Joseph L. Mankiewicz – 1969 – US – 181m

*****

Not-for profit documentary charts the career of non-violent, civil rights activist Dr. Martin Luther King and the role he played in that movement – plays at a free screening 6 for 6.30 start at Union Chapel, Islington on Wednesday, March 29th

An attempt to document the life and work of Dr. Martin Luther King from 1955 to 1968. If you had any doubt as to the subject matter, it goes straight in with a pro-Black Power activist (not Dr. King) making a speech to an enthusiastic black audience. Then it cuts to Dr. King, talking about power – but not the power of the Molotov Cocktail. “But,” he says, “we DO have a power. As old as the insights of Jesus of Nazareth and as modern as the techniques of… Gandhi.”

Dr. King was a great orator, and removing his words, cutting them down (in an attempt to distil their essence) and posting them in this verbal review loses much of the qualities seen in footage of the great man speaking, his presence, his phrasing, the way he uses pauses and so on. He must have been incredible to watch in the flesh as an orator, and while it’s true that seeing his oration captured on film is, inevitably, not the same as the experience of watching him live, the footage of him speaking is both astonishing and compelling.

There’s a lot of minutes here, too. The film clocks in at just over three hours (helpfully separated by an intermission around the 90 minute mark) but it needs those three hours to do justice to its subject. My rule of thumb for such things is, few films need to be longer than 96 minutes, and those that are longer than that had better have a pretty good reason or reasons for being longer. The amount of material in King: A Filmed Record… more than justifies its length.

Where others talk about the needs of black people – which is great for a black audience but not so great if you’re white – King talks about things like the network of communality. The rich person can’t be what he’s meant to be if not everyone is what they’re meant to be. We’re all connected.

It comes over loud and clear from the opening that in advocating the equal rights of black people, Dr. King never advocated violence (although many other pro-black orators did). Quite the opposite, in fact: he constantly warned against its use.

As a bonus, although she was very much part of the whole movement, integral to it rather than something tacked on, there is footage of the extraordinary Gospel signer Mahalia Jackson performing to audiences and crowds who have come to hear Dr. King. Just as his faith was integral to his fight for justice, something into which he poured all the creativity he could muster, so it is with Jackson singing for her Lord, pushing her voice to unimaginable limits rarely seen or heard since.

The film was originally shown in US cinemas as a one night only event on March 20, 1970 with cinemas donating their facilities. It was conceived and put together by producer Ely Landau and directed by two Hollywood heavyweights more familiar with non-documentary, narrative features – Sidney Lumet (Dog Day Afternoon, 1975; Fail-Safe, 1964, 12 Angry Men 1957) and Joseph L. Mankiewicz (Sleuth, 1972; All About Eve, 1950; The Ghost And Mrs. Muir, 1947), yet their sense of story serves them well here.

To break up the three hours and make the material more digestible, sequences are inserted in which various A-List Hollywood actors of the day – Harry Belafonte, Ruby Dee, Ben Gazzara, Charlton Heston, James Earl Jones, Burt Lancaster, Paul Newman, Anthony Quinn, Clarence Williams III, Joanne Woodward – deliver monologues to camera underscoring or counterpointing the documentary footage. It’s a sophisticated form of the advertising industry’s product endorsement technique – by lending their presence and names to the film, these stars are aligning themselves with Dr. King and everything he stood for, thereby giving the documentary and its subject an additional credibility it wouldn’t otherwise possess.

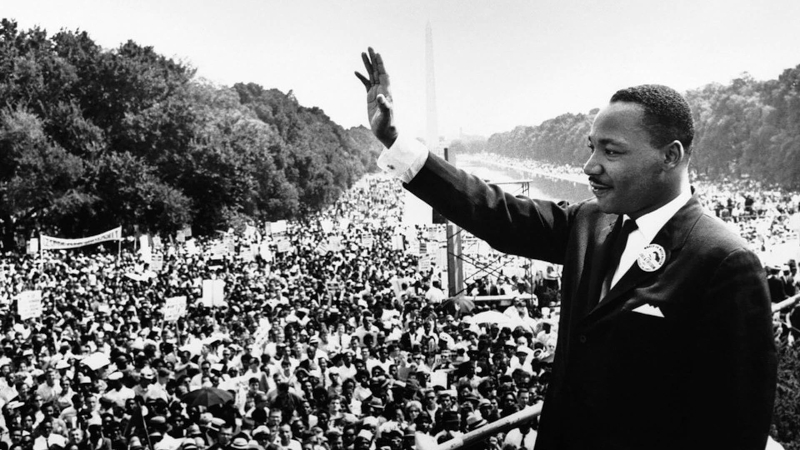

By 1955, when the film’s chronology starts, the moving picture camera had become well established as a means to recording significant events of the day, and Dr. King was news. There exists much footage not only of him both on marches and speaking to meetings, sometimes with enormous crowds in attendance to hear what he had to say. Not to mention footage of protestors for the civil rights cause and their treatment at the hands of the authorities. The two directors make exemplary use of this material.

At the time, there was clearly a national appetite for moving images detailing what was going on; as the figurehead for the non-violent campaigning of equal rights for black people, Dr. King’s cause was nothing if not controversial. The famous march to Selma, Alabama, actually took three attempts because of resistance on the part of local officials who mobilised resources to block and intimidate the marchers. Only on the third attempt, when Washington ordered in the National Guard to protect the civil rights protestors and ensure their successful staging of a peaceful protest as was their constitutional right, did the march reach its intended destination.

Some of the protest footage is a frightening revelation into the soul of white-dominated America. At one point, blacks intent on registering to vote (as is their right under the US constitution) are harassed off the steps outside the office where they are waiting in an orderly fashion by white cops. Elsewhere, Sheriff Jim Clark, who is outspoken about keeping blacks in their lower social place, can be seen sporting a badge which says, simply, ‘never’. Eventually, we see white counter-protestors who have come out in force to show that they disagree with the peacefully protesting backs and want to maintain the status quo: it’s the ugly face of America at that time. (Think of more recent American history, and the white, conservative base of Trump supporters: this demographic hasn’t gone away – it’s still there.)

The cameras didn’t capture everything, and as you near the close of the piece, Dr. King’s assassination is revealed in a spoken message to an understandably shocked gathering of supporters before cutting to footage of his funeral for the last ten minutes or so while we hear the great Nina Simone sing her moving tribute, Why, The King Of Love Is Dead.

The funeral here serves much the same function as it did in real life – after seeing this man’s extraordinary achievements, brought about by a mixture of deep convictions of his faith and a dogged persistence to keep going until the job (or, at least, his part of it) was done – you feel, like those gathered to pay their last respects, both a terrible sense of loss and a powerful sense of achievement, of a life that made a huge difference and actually meant something significant.

King: A Filmed Record… Montgomery To Memphis plays at a free screening 6 for 6.30 start at Union Chapel, Islington on Wednesday, March 29th. Booking advised, details here.

Trailer: