Director – Margy Kinmonth – 2025 – UK – Cert. 12a – 89m

*****

A look at the output of various women artists who have documented and dissected war, and what they can tell us – out in UK cinemas on Friday, March 28th

Although being promoted, reasonably enough, with an image from World War Two of women working with barrage balloons, right from the start in narration over its opening titles this breaks the mould for anyone expecting it to cover any one specific historical or geographical war. “I’m going to talk to women all round the world”, says director Kinmonth in regard to the concept of war as a catalyst for creativity. “What do women see that men don’t?” Quite apart from her gender, she is well-placed to tackle such a subject having recently made two documentaries on the subject of war artists: Eric Ravilious: Drawn to War (2022), War Art with Eddie Redmayne (2015), and many more before that on the subject of art in assorted social contexts.

The film is a compendium of interviews with living female artists or, in the cases of artists who’ve passed on, their descendants or proponents. Some of the names are familiar, such as Lee Miller, Maggi Hambling or Dame Rachel Whiteread, others much less so. The vast majority were born in the twentieth century, with one or two in the nineteenth. Equally with the wars covered, which range through the last hundred years or so (and the Battle of Hastings, 1066!) and cover not only big, obvious conflicts with which the Western World was involved like World War Two Vietnam, and the current conflicts in Ukraine and Palestine but also less widely discussed conflicts in Mozambique, Darfour, Nigeria and Sudan.

It starts off with the controversy at the Venice Biennale, where current global conflicts played out in the form of a Palestinian Protest at the American Pavilion, while elsewhere an Israeli artist closed her exhibition calling for a ceasefire. The Russians were not invited, and the Ukrainian flag fluttered over the city.

Ukranian artist Zhanna Kadyrova lives and works under constant bombardment. An image of a room with a missile come through the ceiling and a computer keyboard and screen underscores the fact. The government collects all missiles as evidence of war crimes. Following the Ukrainian idea of Pallanytsia – or “welcome bread” – which is used as part of general hospitality, she collected stones that looked like bread and cut them accordingly. (There seems to this writer to contain obvious Biblical symbolism, but Kinmonth doesn’t go there.) In Ukraine, Kadyrova explains, wearing what looks like an AC/DC T-shirt, the word Pallanytsiais used as a password to distinguish who is Ukranian and who is not, as Russians don’t have the bread and can’t pronounce the word.

Elsehwere, Zhanna takes tiles on the walls of bombed-out buildings and, by virtue of such visual conceits as tiles reconstituted in the shape of a smock hanging on a hanger, transforms them in situ into installations. As we watch Kadyrova using heavy lifting gear rescue a sculpture from the Donetsk region, Kinmouth comments on the soundtrack that one of the costs of war is the annihilation of culture and identity. Another series of artworks by Kadyrova is her Sticker Project, using an image of a rocket in flight with a fuel trail behind made into a window sticker, filmed on a travelling car window and posted on social media to deliver to a wide audience images of the rocket flying over peaceful world cities. “We want to live on our land”, says Zhanna. “Just because of this, they kill us.”

When in 1992 the then British PM Margaret Thatcher despatched forces to the South Atlantic to defend the Falkland Islands, Linda Kitson was embedded with them as a war artist with the brief to make an apolitical, artistic record of events. She was one of the few women on board, alongside thousands of men; there were a couple of other women, nurses, “somewhere below”. “You bond with others in danger,” she says, recalling freezing conditions in which she had to draw. “Five layers over your fingers – you couldn’t feel anything.” She worked quickly and made numerous drawings, but has one regret. When confronted with boys burned in the Galahad, she thought, “no, no, no” and didn’t draw them. But in retrospect, she feels it was the wrong decision: “I should have said, this is history.” The reactions of the men’s families confirmed her later thoughts: they thought these images should have been seen, as they clearly showed the consequences of war.

Shortly before Iran’s 1979 revolution, Shirin Neshat left Iran for New York City to study art. She still works in that city. She talks about women in war zones as fragile, weak and vulnerable – but also defiant, strong, rebellious and resilient. She makes images of women overwritten with verbal text – the intersection of violence and death. She talks of the anger of Iranian women being forced to wear veils since 1979, and how this widespread resentment bubbled up into the Women Life Freedom uprising of 2022-3. It’s a conflict far from resolved, as we are reminded by footage of a (male) member of the Morality Police hitting a female protester and bundling her into a car.

Dame Penelope Lively remembers her aunt Rachel Reckitt, who became determined to record the plight of the London homeless during the Blitz. She drove there every day and worked on wood engravings showing facades of Blitzed houses – sides damaged and sometimes blown off to reveal the interiors as they had previously been. The excitement of war stimulated her as a person, remembers Lively, and turned her into a staunch Labour supporter.

The outbreak of WW2 drove Gladys Hines to paint a crucifixion with a difference: a woman crucified on the form of a flying warplane. Patricia Thorncroft, who wasn’t licenced as an official war artist, painted an air raid scene from memory in which a horse had impaled its head on sharp railings.

The first female member of the Royal Academy, Dame Laura Knight, won top prize in the RA Summer Show with a picture of a factory girl working in a factory producing anti-aircraft guns. She found herself commissioned to make wartime propaganda to inspire women in the war effort, for instance by joining Balloon Command. As more women entered the workforce, Kinmouth’s own mother worked on Enigma at Bletchley Park, something she regarded as a job no more nor less important than any other. The director quite understandably can’t resist showing her mother’s later commemoration in art in the form of a commemorative postage stamp half a century later.

The film switches to American war photographer Lee Miller, formerly a fashion model and later a photographer for London Vogue, who according to her granddaughter Ami Bouhassane, who today manages Miller’s archives, was driven by a sense of injustice. Images captured during 57 nights of the Blitz included a portrait of ATS searchlight women, primary Luftwaffe targets in air raids as soon as they turned their searchlight beams on. Prior to that, Miller had produced wartime fashion photos to encourage US support before it was forthcoming, an observation has a curiously ironic, contemporary resonance given the US government’s current attitude of withdrawing military support for Europe.

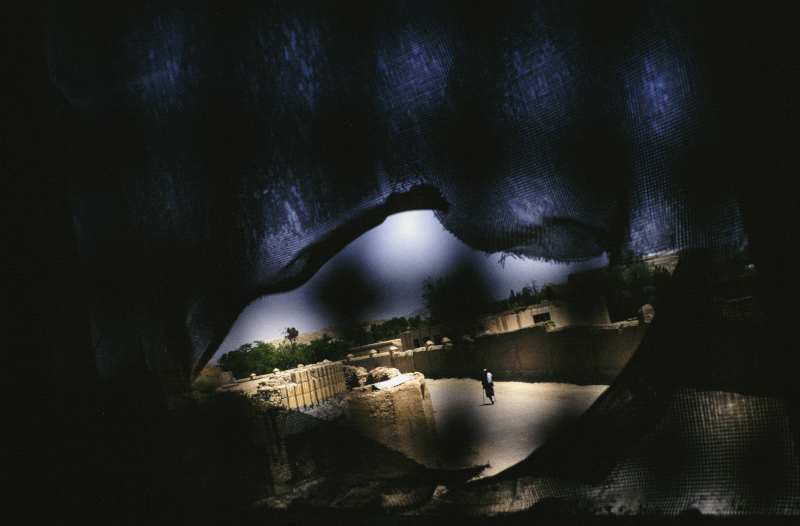

Photographer Nina Berman, who works out of New York, documents war and militarism or, as she terms it, “war-making”, a concept that she sees as the very foundation of the US economy which presents war as something fun, pleasurable and seductive. Shown taking photographs when a 60’ long quilt made by Palestinian Women is unfolded on the steps of the Museum of Modern Art, she describes her role as “amplifying the stories that are being told”. She talks about her work in Afghanistan in the 1990s, which includes shooting photographs through a burka. She also worked in Vietnam, photographing women who had miscarried as the result of Agent Orange poisoning. Bemoaning the gender imbalance in war reportage, she talks about the large number of US soldiers who committed rape in the field.

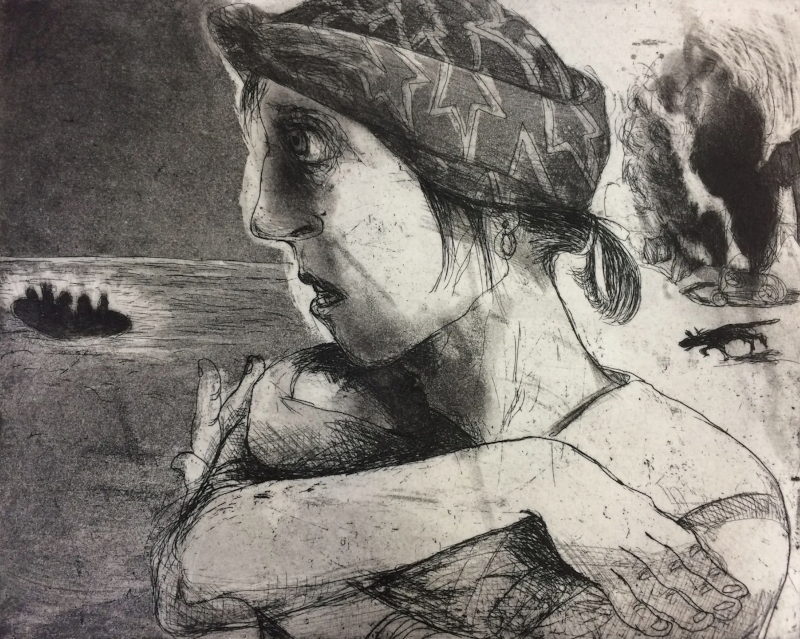

This leads to an image from the Bayeux Tapestry – the film’s only excursion to anything prior to the twentieth century – showing a rape scene, rape as a weapon of war, stitched by nuns. Dutch artist Marcelle Hanselaar describes herself as a witness who produces images of women discarded after rape.

Other women artists interviewed include Assil Diab who spray paints murals onto walls in Sudan, where a largely forgotten war has raged for decades, in an attempt to make visible martyrs in the war. Meanwhile, children’s drawings of the 2005 genocide in Darfur have been used as evidence of crimes against humanity in the European Court of Human Rights. there’s a look at a quilt created by women during WW2 imprisoned in a camp in Changi, Singapore.

Dame Rachel Whiteread discusses her Austrian memorial to the Holocaust, in which culture, she suggests, that atrocity had been largely forgotten. Architect Maya Lin talks about her Vietnam War Memorial in Washington DC, which confronts the viewer with 5 700 names of the war dead before requiring the visitor to turn away and into the light.

The film, and the various women featured, together provide an altogether extraordinary panorama of witness and exploration of the level of atrocity to which human beings are capable of sinking. As such, it makes for essential viewing.

War Paint: Women at War is out in cinemas in the UK on Friday, March 28th.

Trailer: