Director – Amy Berg – 2025 – US – Cert. 15 – 106m

***1/2

A look at the life of the hugely talented singer / songwriter whose career in the 1990s was cut short by his untimely death – out in UK cinemas on Friday, February 13th

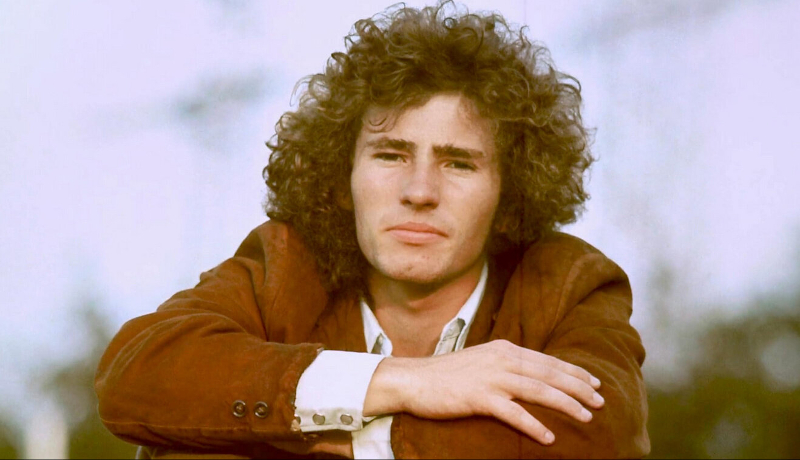

It’s tempting to place Jeff Buckley among the all too long list of rock and roll music casualties who killed themselves via a mixture of excessive lifestyle and drug abuse, a list which includes Jeff’s absent, singer / songwriter father Tim, who died of a morphine and heroin overdose at age 28.

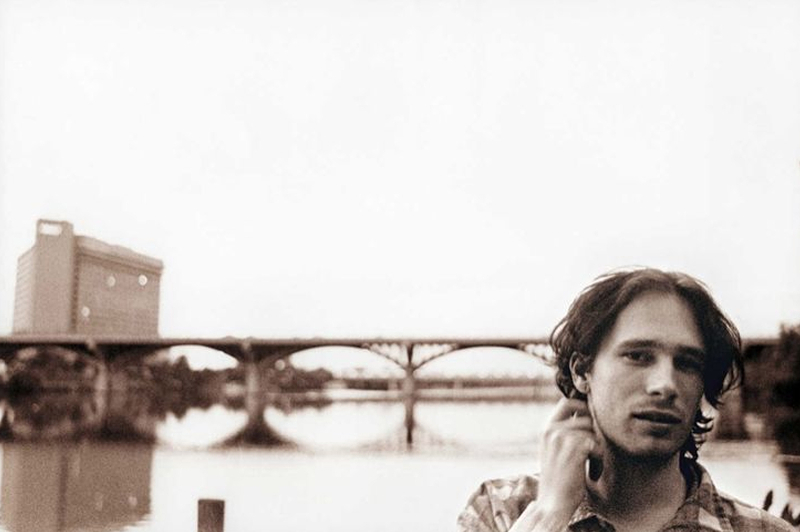

This documentary charts its subject’s life chronologically and thus doesn’t get to the issue of Jeff’s death until late on. Following his early years as a young hopeful living in New York City, Jeff Buckley relocated to Memphis where one day, aged 30, he swam out into the Wolf River (a tributary of the Mississippi) and was never seen alive again. The autopsy, which was pretty much open and shut, recorded that he had one beer in his system. Nothing else. The river at this location had a powerful undertow, so Buckley’s untimely death can be put down to a tragic combination of ignorance and misjudgement.

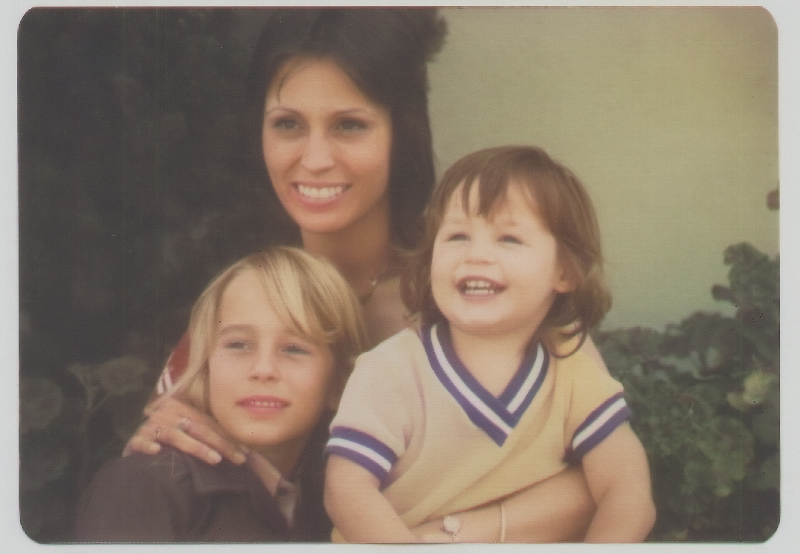

Tim Buckley’s death is all over the piece, however; something that clearly affected Jeff who felt that, once he himself reached 28 years of age, he was living on borrowed time. His second serious girlfriend, musician Joan Wasser (later Joan as Policewoman), recalls him telling her something to this effect. Jeff never really knew his father, who kept his mother Mary Guibert in limbo until it became apparent when she was five months pregnant he wasn’t going to stick around to raise his child. Mary had ambitions to be a concert pianist, but all that went out the window as she was left to raise her child alone.

Growing up, as you might expect from the son of two musicians, Jeff was a sponge, constantly absorbing music of all varieties. Classical from his mum, Led Zeppelin and other rock music from his Uncle Ron. There as a large speaker in the house and as a child he would lie atop it, letting the bass vibrations pass through him. From age 14, he was playing in bands. He channelled Nina Simone in his singing, but his one true musical love throughout his life remained Zeppelin.

In his twenties, attending with a friend a French music festival where Page and Plant were performing, he disappeared until spotted halfway up the stage scaffolding, his body absorbing the vibrations as he had as a speaker-prone child, gesturing, come on up. Yet strangely, considering Jeff was once described as Page and Plant rolled into one – something that mirrors my own observations when I heard the album Grace for the first time – there is surprisingly little material here exploring that comparison.

A chance advert of Tim playing locally at a “minors welcome” gig led to his mother taking the eight-year-old boy to the gig, where his father took an immediate interest in the green room afterwards and suggested Jeff come and stay with him a while. The ‘while’ turned out to be four days, after which Tim put Jeff on a bus back home, then phoned the boy’s mother to inform her. Father gave son his phone number on a hotel matches cardboard fold, but the son’s calls were never answered or returned.

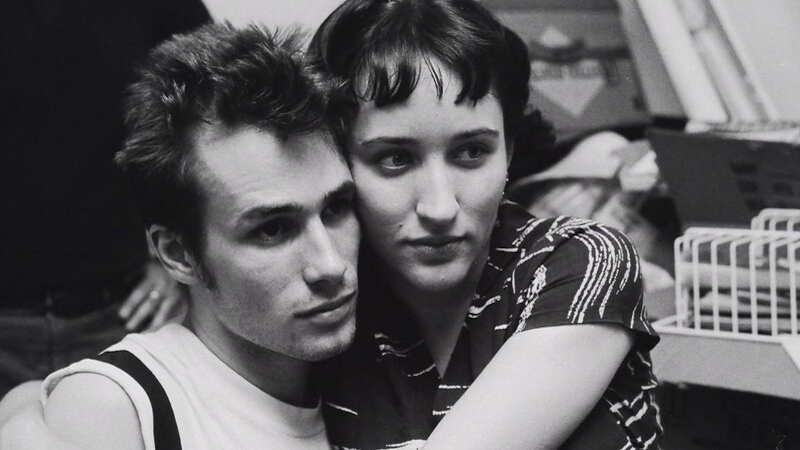

After initially turning down a memorial gig for his late father, the then unknown Jeff performed a song his father had written about him, in fact about how Tim couldn’t cope with fatherhood. It was a personal thing, an act of clearing the decks so he’s never have to perform the song again. At the gig, he met experimental theatre actress Rebecca Moore, with whom he lived until his fame as a musician started to grow later.

There’s a story of his buying all his father’s CDs, listening to them, then tossing them in the garbage. Jeff had an uncanny ability to listen to music and then reproduce every vocal inflection he’s heard. Nevertheless, in the case of his father, you get the impression he needed to listen to the songs to flush his unfit father out of his system.

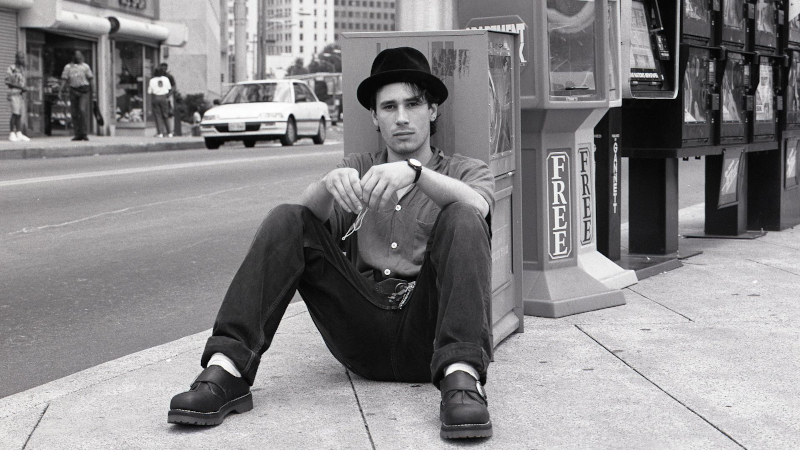

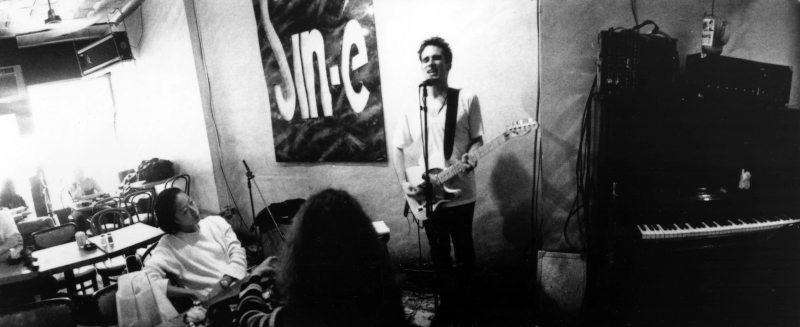

Jeff started to build a small cult audience when working tables at Greenwich Village cafe Sin-e, at first playing covers, later introducing a few of his own compositions. The audiences grew until the thirty or so seats were filled and punters, including many record company people, spilled out onto the streets. He decided to look at record companies, and was immediately impressed by the artists signed to Columbia Records when he saw photos of Bob Dylan and Miles Davis in the lobby. He knew this was where he wanted to be.

Once signed – with a 40-page contract! – he pursued a vigorous work ethic so as to have a roster of his own written songs. As he immersed himself in this, Rebecca found it impossible to continue their relationship, and understandably left him. He later had a relationship with singer Joan Waser.

There is a considerable amount of home movie footage of Jeff, and the two sets of interviews with both his mother Mary and first girlfriend Rebecca are extensive and fascinating. This must have been a nightmare to go through and sort, just in terms of its sheer quantity. The whole thing is intermittently punctuated by arresting and highly graphic (if primitive in style) animation. All that’s good, and yet, somehow, it doesn’t do its subject justice, feeling like yet another music documentary rather than something truly special. Which is to say, Jeff Buckley was a monumental talent whose all too brief career marked him out as something very special indeed, whereas this passable documentary about him fails to rise above the average music documentary when, with a little more vision, it could have been something truly great.

It’s Never Over, Jeff Buckley is out in cinemas in the UK on Friday, February 13th.

Trailer: