Director – Mike Flanagan – 2024 – US – Cert. 15 – 110m

*****

From the End of the World to the life and essence of what defines one man – remarkable Stephen King adaptation is out in UK cinemas on Wednesday, August 20th

This is an adaptation of a Stephen King novella, originally one of the four stories comprising the volume If It Bleeds, published in 2020. King is known as a horror writer, but every so often he comes up with something that defies that mould, including stories that have been turned into such films as Stand by Me (Rob Reiner, 1986), The Shawshank Redemption (Frank Darabont, 1994) and Apt Pupil (Bryan Singer, 1998). His story The Life of Chuck is different again.

And, as is apparent from its outset, it employs a three act structure – a standard device in classic Hollywood screenwriting that makes the property the obvious basis for a film for any filmmaker savvy enough to spot that element – which the author unexpectedly flips on its head by reversing it. Inspired, in part, by that structure, Mike Flanagan’s film follows this template, starting off with a title card announcing Act 3 and then proceeding to tell its three related acts, all of which in one way of another concern defining moments in the life of a man named Charles Krantz (his dying in hospital, an episode one day in his adult life, an experience in his childhood). Each act has its own unique cast, yet the stories, being ultimately about the same person, are linked on a deep level.

The first story (Act 3) fits neatly into that well-worn genre, the End of the World story. What’s the fascination with this? Well, each of us is one day going to die and disappear from this world, and perhaps such stories are part of a way of dealing with that inescapable fact. One might say that about horror fiction or horror movies, which might place the novella within King’s larger body of work. In his story The Life of Chuck, King pushes this further: he takes an ordinary man (name: Charles Krantz) and places his name and image at the centre of his described apocalypse.

As school teacher Marty Anderson (Chiwetel Ejiofor from 12 Years a Slave, Steve McQueen, 2013; Serenity, Joss Whedon, 2005; Love Actually, Richard Curtis, 2003; Dirty Pretty Things, Stephen Frears, 2002; Amistad, Steven Spielberg, 1997) conducts a series of post-schoolday PTA meetings, none of the parents can talk about their child’s progress in school. Each of them, in a series of discussion sequences with the teacher, is distracted by the fact of the internet having finally gone down, following the experience of intermittent outages for the last eight months. Much of California has fallen into the sea. One father, whose wife left him, is particularly grieved by the loss of Pornhub.

With people abandoning gridlocked cars and walking to get to or from work – if they can be bothered – and travel consequently taking longer, not to mention the pace of life imminently slowing down, the conversation continues between Marty and his neighbours, such as Gus Wilfong (Matthew Lillard from Twin Peaks, TV series, 2017; Scooby-Doo, Raja Gosnell, 2002; Scream, Wes Craven, 1996; Serial Mom, John Waters, 1994). Marty himself is not without his own grief, contacting his ex-wife Felicia Gordon (Karen Gillan from Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2, James Gunn, 2017; The Big Short, Adam McKay, 2015; Guardians of the Galaxy, James Gunn, 2014; Dr. Who, TV series, 2008-13), a nurse, for whom he still harbours feelings, to see how she’s doing and perhaps spend some time with her before the world as we know it comes to an end. As is often the way in life, en route there are further significant conversations with strangers, most notably Sam Yarbrough (Carl Lumbly from Captain America: Brave New World, Julius Onah, 2025; Doctor. Sleep, Mike Flanagan, 2019; To Sleep with Anger, Charles Burnett, 1990; The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension, W.D. Richter,1984; Escape From Alcatraz, Don Siegel, 1979).

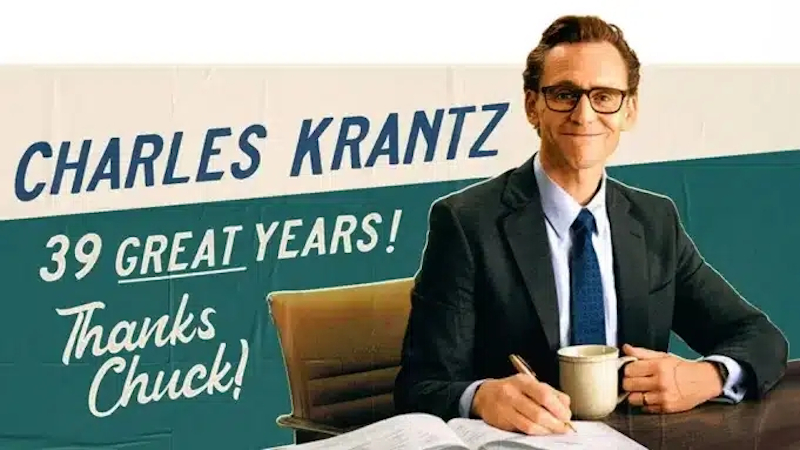

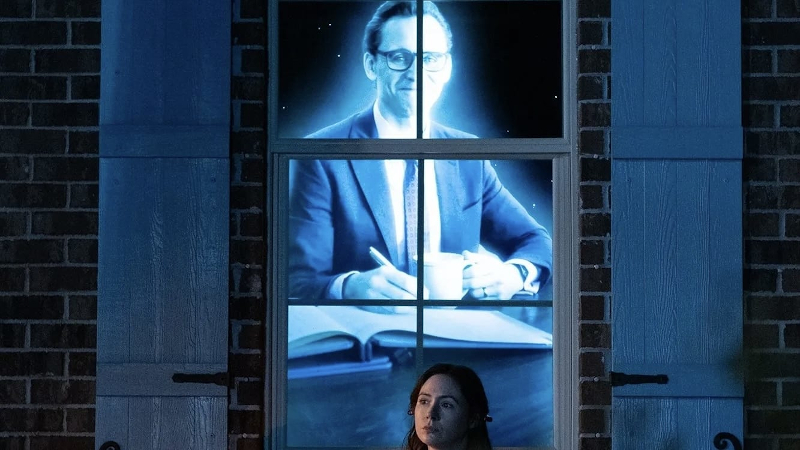

Billboards spring up proclaiming: Charles Krantz 39 Great Years. Thanks Chuck! …and showing a picture of the man (Tom Hiddleston from Loki, TV series, 2016-25; The Night Manager, TV series, 2016-25; Early Man, Nick Park, 2018). TV network transmission cuts out and this same image and slogan cuts in. Later, when it’s dark, as Marty visits Felicia in her residential area, and they stand in the street, the lights in the windows go out as if in a power blackout, only to be replaced soon after with the uncanny glowing image and slogan of the Chuck Krantz billboards. Then the stars start to go out, one by one. Apparently, it’s the end. Of everything.

The image of (a) man. Man is made in the Image of God. That would be any man or woman, for instance Charles Krantz. But who IS Charles Krantz. The billboards, and later the glowing images on darkened windows, which play like bizarre reconfigurations of stained-glass windows in a church – they look nothing like that yet somehow they seem to fulfil in the same architectural function – are visible to everyone (and, for the blind, there are audible spoken slogans – TV spot soundtracks, radio ads). As the apocalypse proceeds, the question of Charles Krantz’ identity, who he is or was, is on everybody’s lips.

No-one knows who Chuck is. Yet, he is dying in hospital, his wife in attendance. In a sense, he is nobody – not a celebrity or a significant historical figure, just an ordinary person who has lived their life which is now nearing its end. Again, who was he? The question as to who he was is the question the remaining two stories about him set out to address.

The second story (Act 2), set on a sunny day, has a girl named Taylor Franck (The Pocket Queen from Peace Through Music: A Global Event for the Environment, multiple directors, 2021) set up a drum kit on the street and start playing compelling, infectious rhythms. Smartly suited Tom Hiddleston (i.e. Charles Krantz), walking down the street, suddenly bursts into a show-stopping dance routine, soon joined by a woman in a swirling red dress (Annalise Basso from Snowpiercer, TV series, 2020-22). It seems to go on forever, one of those wonderful moments or events in life that will stay with you and somehow help to define what you are about. This is Charles Krantz.

The third story (Act 1) concerns the childhood of Chuck (Cody Flanagan; Benjamin Pajak; Jacob Tremblay from Luca, Enrico Casarosa, 2021; Doctor Sleep; Room, Lenny Abrahamson, 2015), his parents’ early death, his grandmother (Mia Sara from Timecop, Peter Hyams, 1994; Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, John Hughes, 1986; Legend, Ridley Scott, 1985) who would dance in the kitchen twirling her fingers like the grown Chuck will do on that later Summer’s day, and his grandfather (Mark Hamill from the Star Wars franchise in an extraordinary, career re-defining performance).

The latter is mostly kind and lenient, but has seen ghosts in the house cupola which he keeps locked and out of bounds, something of an obsession which only makes the young boy want to take the padlock key and gain entrance, should the opportunity arise.

Chuck has enrolled in the High School dance class, a hobby he loves and for which he has a real talent. Yet, he lets his grandfather talk him out of dancing for a career when accountancy is so much more financially dependable. Besides, accountancy is all about maths, and everything, including dancing, can be described in terms of maths. And so, the future direction of a life is defined.

The Life of Chuck is out in cinemas in the UK on Wednesday, August 20th.

[See also my shorter review for Reform magazine.]

Trailer: