Director – Gabriel Range – 2020 – UK – Cert. 15 – 109m

****

In 1971, an unknown David Bowie tours America to promote his new album The Man Who Sold The World – on VoD from Friday, January 15th

The late David Bowie remains one of the most significant and iconic musicians, artists or stars of the last century. Aside from numerous clips of him performing music or being interviewed of radio or TV, he has a presence in a number of films, among them science fiction adventure The Man Who Fell to Earth (Nicholas Roeg, 1976) and Japanese POW outing Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence (Nagisa Oshima, 1983). So if you’re going to try and recreate Bowie on film, you’d better be sure of what you’re doing.

On paper, Stardust seems to be doing everything right. Director Range is first and foremost a Bowie admirer familiar with the music, the albums, the wider body of work, the man. You’d have to be in order to make a film like this. And he’s honed in on a particular episode of Bowie’s life – a very interesting one too, the period in the early seventies when he was known for little more than two seeming novelty records, The Laughing Gnome and Space Oddity, the latter now widely regarded as one of his finest songs. At this stage in his career, much of his songwriting and music performance was in the singer/songwriter with an acoustic guitar vein. He’d just cut the album The Man Who Sold The World which was rockier than anything that preceded it. And he was about to tour the US to promote it.

Bowie was also fighting off some fairly personal demons at the time. His family was riddled with mental health issues. His older half-brother and mentor Terry Burns, who had introduced him to records and taken him to gigs, battled schizophrenia, spent time as a patient in a mental hospital and would commit suicide a decade or so later.

Range attempts to tackle all this with a screenplay that doesn’t go for an entire life biopic featuring all greatest hits but rather attempts to get inside the mind of the embryonic and as yet unknown star. He opens the film with Bowie (Johnny Flynn) as an astronaut in 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968) killed by the HAL 9000 computer, his corpse sent hurtling into space. It doesn’t look quite right (Kubrick was a notorious perfectionist and obsessive and the sequence doesn’t possess quite the same level of detail).

Johnny Flynn is a singer/songwriter as well as an actor (he’s terrific in Beast, Michael Pearce, 2017) but he can’t quite achieve an equivalent presence to Bowie on the screen. He has some of it – the nervousness, the fragility – and he convinces when performing cover songs from the Bowie oeuvre such as Jaques Brel’s Amsterdam. The Bowie estate didn’t give permission for his songs to be used, but most of the time the cover versions seem to get round this problem. Yet there was an almost godlike presence to the real life Bowie which Flynn’s performance fails to match.

You believe Bowie’s spats with hapless American PR man for Mercury Records’ Rob Oberman (a winsome turn from writer and comedian Marc Maron) who tries to make him famous on a microbudget while Jena Malone impresses as wife Angie Bowie, back home in Britain and reduced to secondary character status. The even more peripheral, disintegrating personality of Terry Burns (Derek Moran) also convinces. But then, unlike Bowie himself, these are not people who have been on our screens for forty of the last forty five years. An actor can play them and we’ll believe them to be real.

None of these actors’ portrayals of their characters has to live up to the same level of scrutiny as Flynn’s Bowie. We’ve heard the albums, seen the performances and interviews, watched the movies. It’s a very difficult balancing act Flynn is being asked to pull off. You never really believe he’s David Bowie in the way that you genuinely believe that four different actors are playing four separate versions of the equally iconic Bob Dylan in I’m Not There (Todd Haynes, 2007).

Perhaps Bowie, who later on adopted a whole series of now familiar alter-egos, is considerably more iconic in the present day mind. At the period in which he’s being portrayed here, before we met all those alter-egos, we really need to believe it’s him. What we feel we’re watching is not Bowie but an actor playing him. That sounds obvious, because of course, that’s what we’re watching. However, in the case of Bowie, when you watch one of the films or numerous videos he himself appeared in, you’re really watching him. As soon as you’re watching an actor playing him, as you are here, that actor has to become Bowie to make the illusion work. That’s something Flynn never quite does. Which ultimately undermines the film.

Range sees to be aware of this conundrum, peppering his film with people asking, “who is the real David Bowie” and similar and fracturing his leading man’s face into multiples via a series of mirrors. He uses the promotional tour as a framing device, periodically chopping back to previous events in England, at one point shock cutting to an earlier Flynn/Bowie with much shorter hair as if to suggest an earlier alter-ego. At one point, Bowie says, “I feel like I’m a carnival sideshow, without a carnival” and you can’t help but agree, although not in the sense it’s supposed to be taken. At another, he sits in a hotel room channel hopping and you think, The Man Who Fell To Earth.

Later, Ron says, of Iggy Pop, of who Bowie hasn’t yet heard, “he’s a freak, just like them” (the audience) which seems to anticipate what Bowie will later become, “he is everything you can’t be.” In New York, Flynn/Bowie has a long chat with Lou Reed who turns out not to be Lou Reed but an impersonator. “Rock star or person impersonating a rock star”, says Flynn/Bowie. “What’s the difference?” Then he gets to L.A. and casts lots of reflections in mirrors, on one occasion with them all looking up at different times like different David Bowies. “If you can’t be yourself,” says Ron eventually, “be someone else.”

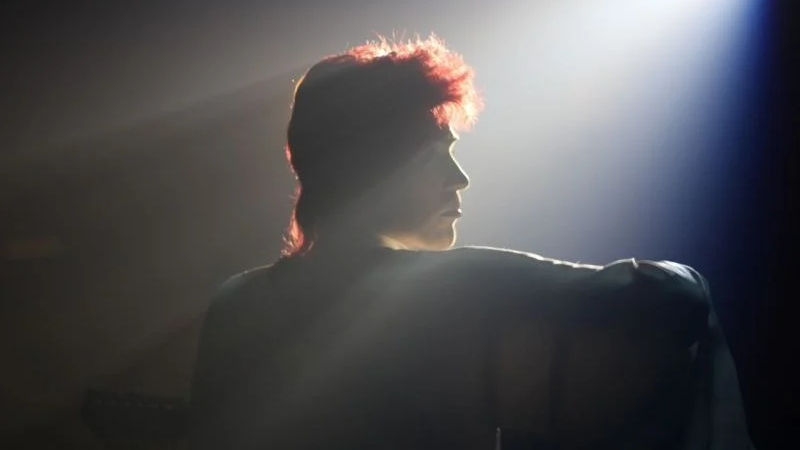

For the finale, the film stages the first gig where he and his band, Mick Ronson (Aaron Poole) et al, go on stage as Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars. Suddenly, with the costumes, you finally believe Flynn is Bowie. Even though he’s not allowed to play an actual Bowie song, it doesn’t seem to matter. After the disappointment of what has gone before, there’s something deeply satisfying about this. Stardust may mostly fail at recreating Bowie, but it remains a brave attempt to get under the skin of the pre-stardom engma.

Stardust is out on VoD in the UK from Friday, January 15th.

Trailer: