Director – Chihiro Amano – 2019 – Japan – Cert. 12a – 106m

****

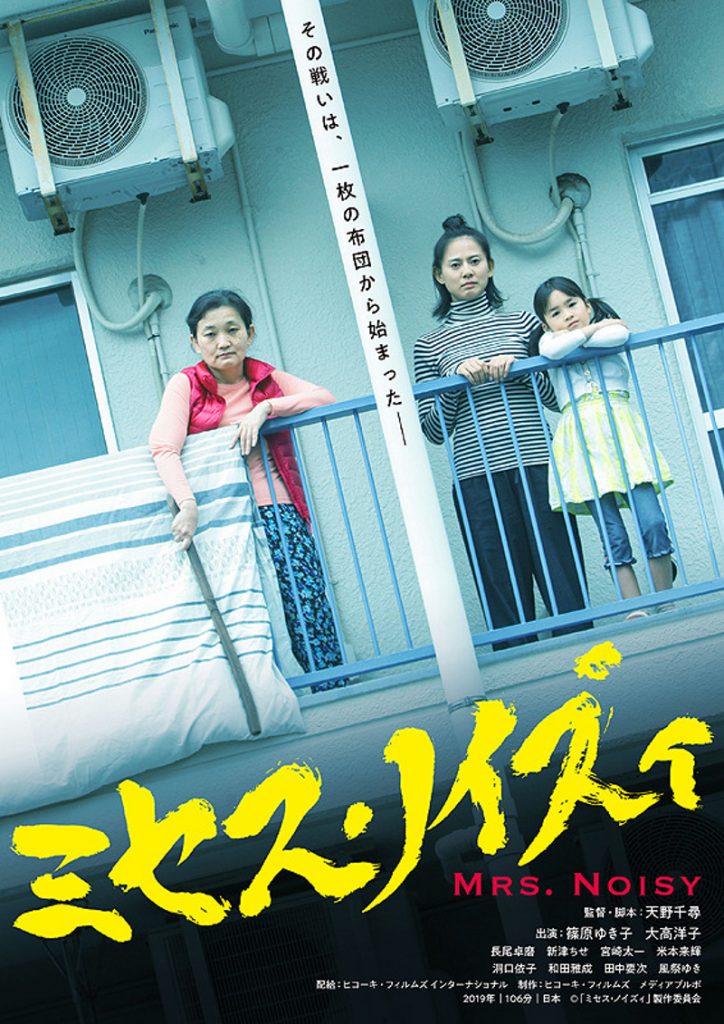

A writer and young mother struggling with an elusive second novel finds herself dealing with a noisy, futon-beating neighbour in a rapidly escalating row exacerbated by viral internet videos – plays online in the Japan Foundation Touring Film Programme 2021 in the UK

Two women neighbours get involved in a petty feud which escalates out of all proportion, fuelled by videos on the internet. While parts of the feud are riotously funny to watch, this is less a comedy and more a warning as to how badly things can go wrong between ordinary people isolated in their separate domestic units in our ever-evolving technological age of phone cameras and social media. The housing block in urban Japan could just as easily be in any city in the UK. It looks all too horribly familiar.

Having published one hugely successful novel, Maki (Yukiko Shinohara) gives birth to a daughter and resolves to use the experience to feed into the next novel. She keeps writing, but her publishers tell her that nothing she’s written is up to par. Six years on Maki, her husband Yuichi (Takuma Nagao) and their small daughter Nako (Chise Niitsu) move into a new flat in a new block hoping that the change of scene will be just what Maki needs to get the writing back up to standard.

Her husband’s freelance work as a sound engineer means that he can’t be at home to babysit as and when, so Maki starts writing late at night and early in the morning in an attempt to hit publisher deadlines. Sometime before 6am she hears loud banging – the lady next door Miwako (Yoko Ootaka) is beating a futon draped over the railings. Unable to work against it, Maki tries to talk to the woman but Miwako won’t stop until she’s ready. “There’s a reason,” she proclaims.

Nako isn’t coping well with her mum being focused on writing rather than looking after her daughter and on a couple of occasions takes herself off to the nice lady next door or the park. On one occasion, Maki and her husband phone the police. Maki becomes convinced that the woman is crazy and her husband, who bathed Nako, is a paedophile.

Things go from bad to worse. On one occasion, she finds herself broom in hand in a battle with the neighbour waged around the adjoining balcony partition. This is filmed by her younger cousin Naoya (Taichi Miyazaki) who happens to be passing and later uploads the video to the internet under the moniker ‘Futon Lady v Rei Mizusawa’, the latter being Maki’s pen name. The title elevates the dispute to the level of two kaiju battling it out on the balcony. The video goes viral almost immediately. Maki is unaware it even exists. Naoya tells her she should use the dispute in her writing. She starts a new story Mrs. Noisy which becomes an immediate hit with her publishers, who serialise it. The youth readers make a connection between the serial and the videos.

Egged on by the social media savvy but morally clueless Naoya and wanting to obtaining video evidence her solicitors can use in court, Maki films another futon beating but this act only serves to goad Miwako into first throwing salt over the partition then, after Maki has thrown a saucepan of miso-coated mackerel at her, ripping down the partition to pursue Maki through her own apartment and along the block walkways, filmed all the while by Naoya who can’t believe his luck.

The narrative then jumps back a month and retells the story from Miwako and her husband’s point of view. Many years ago, the couple lost a son about the same age as Nako and her husband Shigeo has never recovered. His mental condition has deteriorated and he suffers from hallucinations, for instance seeing a family of earwigs crawling in his bed and over his face and head while he sleeps. To calm him before 6 in the morning, she takes the futon out onto the balcony and beats it to get rid of them where she meets first Nako then Maki.

Miwako’s encounters with the neglected Nako lead to her looking after the child while her mother is working, though she foolishly fails to inform Maki of what she’s doing. When the child is in their flat, playing with their son’s toys, they’re like a surrogate family. It seems to do Shigeo good too. Miwako has no comprehension whatsoever of the pressures Maki is under, and simply thinks of her as an unfit mother. The internet, meanwhile, goes with Maki’s unsubstantiated assumption that he’s a paedophile and when he happens to find this online, he attempts suicide by jumping off the balcony.

Maki eventually discovers the videos online, including the one intended for her lawyer which she had expressly forbidden Naoya from uploading, as do her publishers who cancel her wildly successful Mrs Noisy serial. Now the two women must deal with one another and sort this out.

Although the piece veers in tone between the comic and the serious, the viral video subject matter reminded me of the Dutch movie about animal cruelty Find This Dumb Little #Bitch And Throw Her Into A River (Ben Brand, 2017). There as here, a member of the younger generation uploads something to the internet they really shouldn’t. The difference here is that Naoya acts like a knowing internet ‘influencer’ who knows how the game is to be played, but like the protagonist of the earlier film he fundamentally lacks any sort of moral compass and unleashes forces which ultimately he has no means of controlling.

Towards the end, Maki comes to the revelation that she’s been focused on herself and her writing rather than properly doing her job as mother. Yet we’ve seen her under considerable pressure to reproduce the success of her first novel from a publishing industry that simply wants a product it can sell and expects its writers to deliver. When she suddenly seems to be producing such content, her sense of elation is evident and immediate. In the end, though, the awful situation in which she finds herself, which is at least in part of her own making, forces her to write a much deeper version of Mrs. Noisy which we witness Miwako reading, laughing and crying over.

Somehow, to go from the embattled conflict of the two women’s very different life perspectives to a resolution where they talk it all out with each other and everything is okay doesn’t really convince. More believable is Maki’s husband looking as if he’s about to leave her because he’s had enough before she unconvincingly admits the errors of her ways, or the pragmatic landlady giving first Miwako then Maki the third degree and warning they may have to move out, something that comes to pass in the case of Maki and her family.

If Maki’s self-realisation fails to convince, the films doesn’t even begin to try as far as Miwako or Naoya are concerned. Once we’ve seen the story from Miwako’s point of view, the film lets her of the hook when to beat a futon noisily, day after bay, before 6am, is clearly antisocial behaviour whatever the reason behind it.

And while Maki’s fictionalising of their dispute with Miwako is scarcely justifiable, it’s not her but her younger cousin Naoya who initially makes a video then decides to put both that video and one later made by Maki online (even though she expressly tells him it’s intended specifically for her lawyers and most definitely not for publication online).

Yet all the film can manage is a shot of Naoya ambling down a street as if nothing had happened. It’s as if director Amono, having opened Pandora’s box to discuss really difficult and complex moral and media issues, just wants to close the box at the end of the film and put everything back inside. Life doesn’t work like that, though. Especially not with today’s technology.

The internet has arrived and social media with it. Things will never be quite the same – you can’t on the one hand wrestle with issues like this then on the other just wrap up everything neatly as if the characters’ worlds have not been forever changed. The effects of the internet and social media can be devastating in ways we are only just beginning to comprehend. This film goes a long way in understanding some of those issues only to seemingly throw everything away in a quest to satisfy an audience with a happy ending in its coda. Ending notwithstanding, the bulk of its proceedings provide the viewer with considerable food for thought.

Mrs. Noisy plays online in the Japan Foundation Touring Film Programme 2021 in the UK.

Trailer: