1/ Magnetic Rose (Kanojo no Omoide, 彼女の想いで)

2/ Stink Bomb (Saishu Heiki, 最臭兵器)

3/ Cannon Fodder (Taiho no Machi, 大砲の街)

Directors

– 1/ Koji Morimoto, 2/ Tensai Okamura, 3/ Katsuhiro Otomo

– 1995 – Japan – Cert. 12 – 113m

*****

Executive producer Katsuhiro Otomo’s anime anthology adapts three of his dystopian-themed manga stories into animation – out on Blu-ray from All The Anime, Monday, 12th September, details below review

The film that made Otomo’s name and the one with which he’s most frequently associated is Akira (1988). It wasn’t his first film, though. Previously, he was one of nine directors who collaborated on the uneven portmanteau Robot Carnival (1987), a compendium of different animated stories based around robots of various types. One of the other directors was Koji Morimoto.

Memories is loosely similar – it only has three stories (and three directors), allowing each of the segments a bit more room. Its three episodes are very different yet perfectly complement each other. Otomo directed the third section Cannon Fodder.

Parts of the roughly two hour Akira drag, while Otomo’s later Steamboy (2004) gets lost within a massive set piece after a near perfect opening first reel or so. However, the shorter Cannon Fodder seems almost perfectly realised, while the large triptych of the Memories project, on which Otomo was one of four executive producers, performs a deft balancing act. The three tales are very different (one is an obvious opener, one an obvious closer while the third – technically not the third but the second – is the perfect piece to fit in between the other two).

It’s an Otomo film in the sense that all three stories are taken from his original manga collection Memories. The opening Magnetic Rose is a science fictional tale not entirely unrelated to 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968), the middle film Stink Bomb is a cautionary-tale-cum-road-movie about the perils of chemical weapons manufacture while the closing Cannon Fodder riffs on Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four with its tale of a city whose entire economy and culture is geared around a vast gun that must be fired at an enemy city on the other side of a vast plain.

Both the latter two episodes were scripted by Otomo, while the opening one was written by Satoshi Kon who would go on to direct such seminal theatrical anime fare as Perfect Blue (1997), Millennium Actress (2001), Tokyo Godfathers (2003) and Paprika (2006).

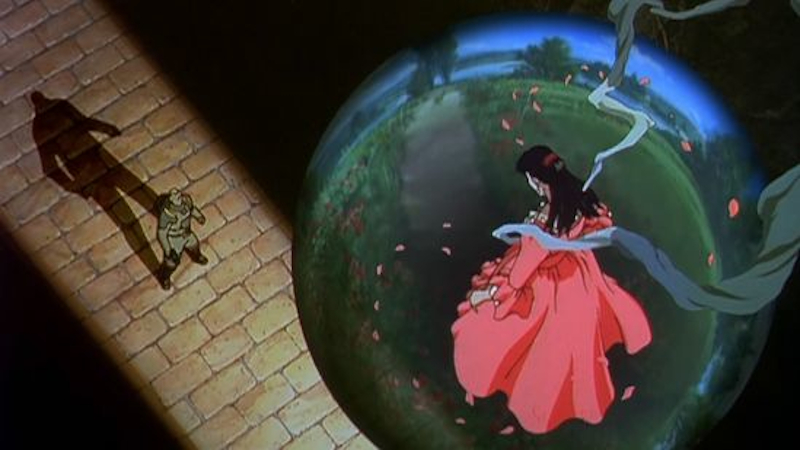

The small salvage spaceship of Magnetic Rose is closer to the space truckers of Alien (Ridley Scott, 1979) who are required to respond to a distress call or the small, planet-busting crew of Dark Star (John Carpenter, 1974) than to the slow moving, by the book Jupiter Mission spaceship of 2001, although once that film launches its lone astronaut into a pod and even more when, at journey’s seeming end, he steps out of the pod into a replica eighteenth century mansion, 2001 comes much closer to Magnetic Rose.

Here, the scenario is that a small scavenger crew making a living off finding space junk for resale stumble into what first appears to be a giant rose in space, then turns out to be the eighteenth century styled mansion of a fading opera singer… with a twist. The singer has long been dead and the crumbling house, like the space station in Solaris (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1972) is somehow bringing the presence of the singer back to life and giving her home a makeover into all its former glory.

As the ship moves into the presence of the house like a moth drawn to a flame, the musical strains of the opera Madame Butterfly loom large, beautifully orchestrated by Yoko Kanno (Macross Plus, TV miniseries,1985; Cowboy Bebop, TV series 1998-9). Science fictional elements give way to horror tropes as the tale plays out.

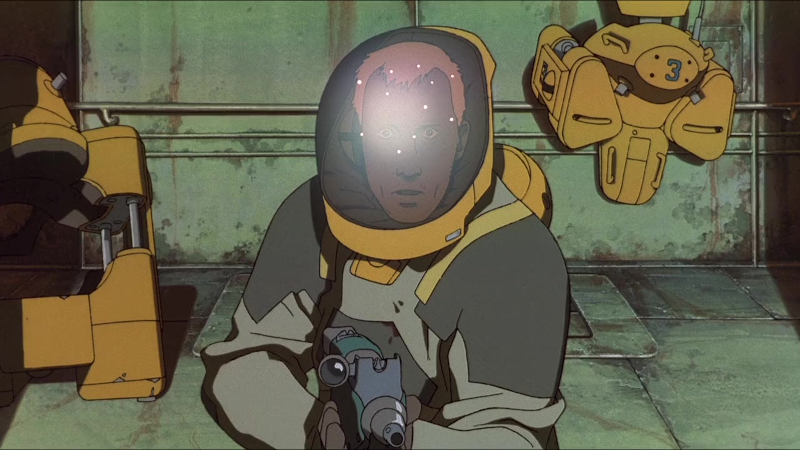

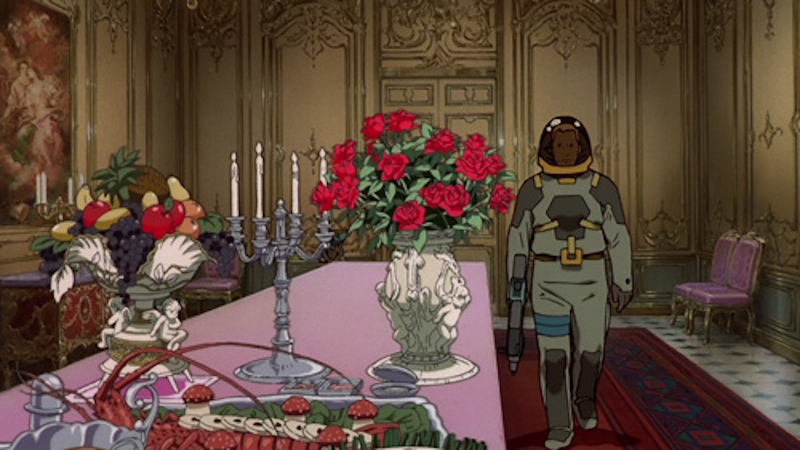

Opening with a cheerfully glib Good Morning TV programme wake up jingle, the second story Stink Bomb feels dangerously close to home under current pandemic conditions. It’s the middle of winter and a run-down chemicals research employee, fighting off a bug and going in to work when he really should have stayed at home, swallows what he presumes to be an anti-flu tablet unaware it’s actually a chemical weapons prototype which turns his body into a weapon of mass destruction to everybody but himself. Haplessly heading across the countryside to report to his corporate bosses in Tokyo, he inadvertently gives off chemicals that wipe out people caught in traffic jams and members of the armed forces sent to halt the advancing ‘gas’.

The storyline recalls the Otomo‑originated anime feature Roujin Z (Hiroyuki Kitakubo, 1991) – a character caught up in technological innovation well beyond his understanding travels towards a specific destination wreaking havoc as he goes, with the military failing to halt him. Visually, it resembles Roujin Z too – though never detrimentally so. The whole has a wild and blackly comic sensibility underscored by Jun Miyake’s demented jazz sax score that ought not to work yet somehow fits perfectly.

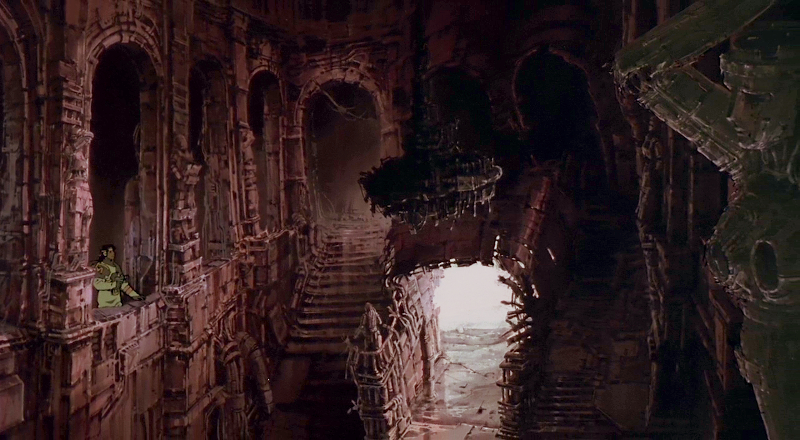

Less densely plotted than its two companion pieces, the dystopian Cannon Fodder centres around a nuclear family of son, mother and father in a militaristic society built around the loading and firing of a giant cannon at a distant (but scarcely known) enemy which constantly repositions itself on the other side of a vast plain. The son goes to school where all his classmates are bored or nodding off as the teacher drones on about wind velocity calculations, the mother to an armaments factory and the father to his lowly team leader position in the complicated chain of command that fires the gun.

Everyone on the gun team works under extreme pressure, and when the father slips up, he is punished by having to stand unprotected by his missing gas mask during the firing, an incident we see no sign of him later discussing with his family. Details small and large underscore war being everything to this society, an alarm clock in the form of a little cannon, evening radio bulletins detailing the success or otherwise of the day’s firings and a portrait in the family’s hallway of a proud man in a soldier’s uniform.

The animation itself is designed as a series of unbroken pans much like the Ave Maria which closes Disney’s Fantasia (Forde Beebe Jr., Jim Handley, Hamilton Luske, 1940), a visual conceit which might easily have got in the way of telling the storytelling but in the event serves it most effectively even as it inspires our wonderment. The martial, otherworldly score is by Hiroyuki Nagashima (Beautiful New Bay Area Project, Kiyoshi Kurosawa, 2013; August In The Water, 1995; Angel Dust, 1994, both Sogo Ishii).

Akira may be widely considered Otomo’s masterpiece, but for me, the more collaborative Memories is at least its equal – if not a better film altogether. Following a brief London Film Festival outing in 1997, it vanished only to later surface as a straight to DVD UK release. The fact that it’s nowhere near as well known here as Akira is nothing less than a travesty. Kudos to Annecy for screening it in 2022.

Memories is out on UK Blu-ray from All The Anime, Monday, 12th September.

Trailer:

Annecy 2022 trailer:

—

2022

UK – Blu-ray release from All The Anime, Monday, 12th September

France – Annecy, Monday, 13th June – Saturday, 18th June

UK – Anime season, BFI Southbank, Monday, 28th March – Tuesday, 31st May

1997

London Film Festival