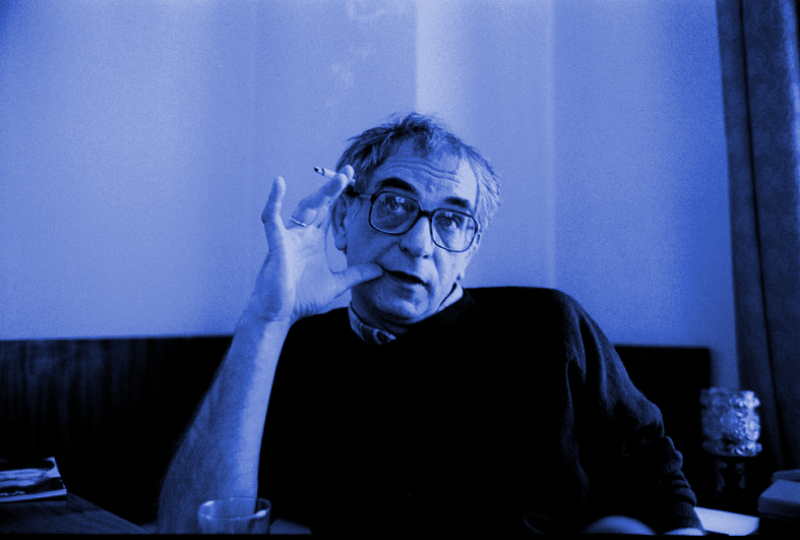

Transcript of interview from 1993 when Kieślowski was promoting Three Colours: Blue. At the time, the other two films in the trilogy had yet to be screened to press.

How far do you consider Three Colours: Blue a separate entity in its own right, and how far the first part of a planned trilogy? “I think it’s a film in its own right.”

Did the initial inspiration come as this film, or rather as the three films? “Well, we started from ideas, from scripts – and since the original idea was such as it was, that included three films. So then we had to answer three questions because there were obviously three problems. We decided fairly early on in our working to make the three separate films, which of course have certain common elements to them. But these are quite carefully camouflaged links, representing my playing around with games for the viewer who also indulges in such games. If the viewer doesn’t like such games, then he’ll just see three entirely different stories. If the viewer likes these, then the films become something more.”

These’ll be something to look forward to later on. “Yes, a few of those feature in Blue, but there aren’t all that many of them. It’ll only become clear when you see the third film why I wanted to make the three.”

Are all three films based around female characters? “No, the second one concerns itself with a man. I’m not a specialist at making films about women, especially as more and more people are accusing me of making films about women from the point of view of a man, not least my wife.”

Did the car crash as a starting point to Blue come early on in the script’s development? “Well, as soon as my co-writer and I, myself came across the idea and decided on the idea as it was and that was the way we used it. Of course, there were various other stories we considered that one could have considered, but we didn’t use those and there weren’t any women either. But then as it turned out we settled on this story. This process of finding the actual story took quite a long time because the films don’t arise through a story. That comes later on, after the idea around which it’s based has become clear.”

Obviously, one could apply this to the current trilogy or the earlier Decalogue (his series of films based around the Ten Commandments – ed). Would you say this represented a general working method for you? Finding a concept and then looking for an appropriate story, as opposed to the other way round. “First, it’s the basic concept and then the characters arise and just have to be given a form of life. It’s true that I do create a film around the characters, so I might say that the story was the most important thing, but in fact the most important element is the main character who experiences the story.”

Did you always have a one-hander in mind, in the sense that Blue is about one particular character? “Yes, once we’d decided on this character, that was so.”

Given that this was to be a film about the French ideal of liberty, in the process of finding that story, that character, was he always sure he’d use a single protagonist? “No, no, initially there were all sorts of stories and characters, but I must say that the French concept of freedom was always somewhere there in the background. Deep in the background. It’s not the most important thing. That’s in all my films. I don’t want to frighten people away by saying that I’ve made a film about the French ideal of freedom. That applies to the English viewer, but also to the French public. I think all viewers are frightened of films like that.”

Certainly, it does sound a little on the heavy side. “So I don’t think I would want to see something as heavy as that. There are films that are very much perceived that way. I can imagine, if that were the case, people saying, “this is supposed to be the French Revolution? The French freedom?” “

Having said that, a woman bereaved of her husband and child does seem a potentially very depressing subject. “Yes, but if you add philosophical ideas to that, it becomes a lot heavier.”

Has he lived in Paris, where the film is set? “No. I’m living there because I’m working there.”

How then would he go about researching the kind of places in which people would live? “I’m somebody who’s come from the outside in Paris, I’m a tourist, so I look for people who can bring this French element with themselves. They bring a different element with themselves, and I depend quite a lot on their views and opinions on things. They know better than I, so I call upon their own experience. This can apply to the producer, the assistant, the set designer and, above all, the actor or actress – who has the French element naturally because she is French.”

“I was at one stage going to use an American actress for Three Colours: Blue, but I realised what a great mistake this would have been. I understood very quickly that this would be a terrible mistake. I know very little about France myself. What can an American actress know about France, how can she feel things? It’s impossible. So I threw that idea away and used a French actress.”

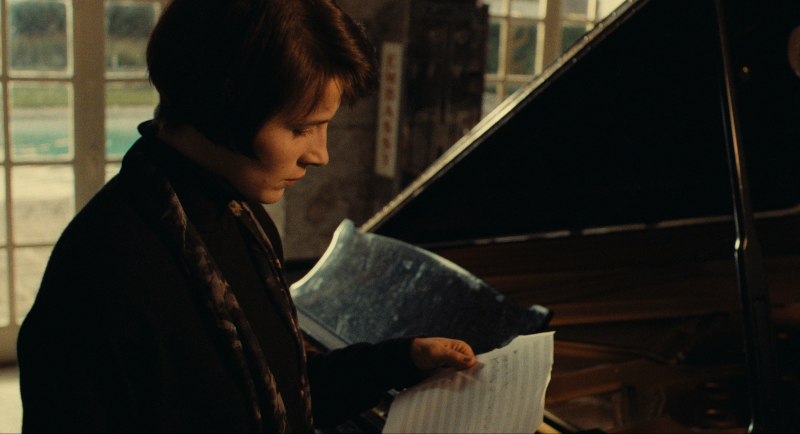

Was Juliette Binoche his first choice, or was she someone he arrived at later on? “Yes, when we were writing the script, we knew we were writing it for her. Even if she did not know that herself. I met her here in London when she was filming Louis Malle’s Damage. She took a long time to sign the contract. But she finally signed.”

What was it about her that made him want her for the role? “She’s a good actress, that’s the first thing. But there’s a lot of good actresses around. I think she has particular characteristics that were necessary to this film – a certain sensitivity and is very strong at the same time. I needed this combination.”

This throws up two of the most enduring images from Blue. The image of the family of mice the woman finds in the flat and doesn’t know how to deal with – and borrows a neighbour’s cat to kill them. Then there’s a man being mugged in the street outside where she’s living in Paris who knocks on doors attempting to get help in her apartment block – and she’s not sure how to deal with that either. This seems to tie in with what he’s saying about the actress’ qualities.

“Yes, of course. It does. The character is a strong woman who makes an important decision. But at the same time, she is subject to various feelings and fears from the external world, such as the fear of mice. She’s fighting some sort of battle within herself, that on the one hand she wants to help and on the other she knows she can’t because she’s taken these certain decisions. She has the ability to stick with them – at least, she certainly can play them out. But she’s a bit like that.”

Does that struggle between those different character traits relate to his concept of liberty in the film? “Yes, it’s very central to this.” (Pause)

Can he explain further? “It’s simply a choice of what we want – what we really want and what we’re capable of doing. For example, with the mice she finds in the flat, she’s probably got nothing against mice as such, but she’s frightened of them. She’s frightened and is incapable of overcoming this fear. She doesn’t want to be afraid, but she is. So it’s a struggle between what she’s capable of doing and what she feels.”

“So she goes to the estate agent’s to ask whether she can have another flat, a different flat. But he says he needs a few months. She goes to her mother and asks whether she was afraid of mice as a child. Her mother says, yes, she was afraid. So she understands that she’s always had this fear. She’s got to understand that she’s incapable of overcoming this fear. So she borrows a cat from a neighbour and lets him into the flat, and then she can’t cope with it. She can’t cope with it, but she can still feel guilty of having killed the mice and complaining of the fact. It is a terrible thing to do.”

“So she asks her friend, the “whore” she befriends, to clear the mess up. This means that, automatically, she becomes dependent on the friend. When this friend asks her to help her one night, she feels an obligation out of gratitude, so she goes. Of course, she then falls into the trap because she sees on the television the mistress her husband had. So it’s a constant struggle to try and overcome herself. Her own feelings, emotions, weaknesses, fear, loneliness. She wants to overcome these, but she can’t.”

It’s interesting that he considers the mice a small detail, since in this way they point up the larger whole of the film. “Well, there are a lot of details like that. The entire film is made up of them!”

Yet, if one had to describe the film in two lines, it’s about a woman who loses her husband in a car crash. He was a composer, there’s this unfinished symphony, will she complete it? Again, this concerns something which she is unable to resolve. Which seems very similar to the mice, in a way. “Yes, you could summarise it that way; there are several ways you could summarise this film. (With a grin.) I have nothing against any of them.”

Does he consider liberty an impossible ideal? I’m thinking of the problems we’ve just discussed that the Juliette Binoche character has to deal with; but as soon as she starts dealing with these problems, she has to deal with people – and as soon as she starts doing that, it clamps down on her freedom. “Because freedom is a pure ideal. Which can’t be achieved. It’s impossible to achieve. It’s not a human state. I think we’re so dependent on ourselves and also on our own experiences that we can’t do away with them. We have to learn to live with them. At the end, that’s what she’s learned to do – accept.”

At the end, the film verbally quotes 1 Corinthians 13 as the various characters are shown onscreen in shot after shot. “Yes, it’s a way of saying, what was said to the Corinthians applies to us all. You and me. I widen the story out at the end in that it also concerns the unborn child in the late composer’s mistress’s womb.”

If he feels that liberty as understood by the French is a concept that we can’t achieve, does he feel the same of the other two ideals of the French Revolution, equality and fraternity (brotherhood). “Equality, certainly we can’t. I’ve not yet met a person who would like to be equal. Everyone wants to be a little more equal. I don’t know whether you can say that in English. Be more equal. But I mean that one person can thus be considered better than another.”

When George Orwell satirised totalitarian rulers as pigs in Animal Farm, they justify their position by saying, “all animals are equal, but some are more equal than others.”

“So I’ve not yet met people who’d like to be equal, although everybody speaks about being equal. Everybody would like to be above everybody else. It’s irrelevant what field that concerns – in the worlds of finance, business, property, but not illness. Each of us would like to suffer less than the next person. Everybody would like to die a little less painfully than everybody else. Everybody would like to be a little less frightened than everybody else. Everybody would like a better car. I think that the concept of equality is very questionable in line with human nature.”

(Re-reading this again in 2023. I realise that I myself would like to be equal. Not the same as everybody else, which is something else again. I consider myself neither superior nor inferior to others. I think all people ought to have equal opportunities in life. I can’t believe I’m the only person who thinks this – I’m sure many others think the same. Perhaps I couldn’t have expressed this so clearly when I was younger.)

“Fraternity’s a slightly different matter. It’s possible to achieve – we have that within ourselves – it’s just a matter of motivating the possibilities. A question of sympathy and help. It’s possible. I think that I think each of us at a certain moment lives it. Even bad people feel these things.”

I find it hard to understand how one could believe equality possible but not brotherhood. They appear to be interlinked. “I think that fraternity’s a hypothetical possibility. I think each of us has this possibility within us. It’s really just a question of putting people in such a situation that it motivates them, whereas I think that equality’s contrary to human nature. Because if you start looking at various examples where the concepts are similar; but if you look at the map a bit more with a wider scope, I think that you can understand the differences.”

Has he found the process of making the three films substantially changing his view of the three concepts of liberty, equality, fraternity. “No, they haven’t changed – but from the beginning, I’ve not known realities. I’m somebody who asks questions, not” (supplies) “answers.”

This makes one wonder how far he himself identifies with Blue‘s protagonist (even though she is, clearly, a woman, and he’s a man). How far is the Juliette Binoche character an embodiment of personal experience? “I identify with each of the characters in my films – to a certain extent. It’s not even a question of identification so much as of understanding. Trying to understand another person. Even though he might do something terrible as, for example, in A Short Film About Killing. I can’t say I identify with him; I’ve never murdered a taxi driver and never will. But I’m certainly trying to understand him. And why life is the way it is. Why he is the way he is, the murderer.”

“Similarly, I’m trying to understand Julie. What happened. Where did she find herself in such a moment, such a situation? Had that happened to somebody else, they might have seen it differently. But I’m trying to understand her, make it deeply personal. How far this makes it a piece of identification, I don’t know – I’m just trying to understand.”

How far was this prompted by personal experience or that of close friends or family who’d lost those close to them? “It’s influenced by people. Like my whole life. My friends, places I go. Things I’ve heard or seen. My co-writer’s life. Everything. Maybe there’s a marriage that fell through. I would never say that.”

The car crash as contemporary nightmare: one minute you’re there telling a joke, the next you’re dead. Or injured, or whatever. How consciously was this a pivotal point to stir up all manner of elements in the Juliette Binoche character? “I think it’s the way we filmed it, that’s what gives it that concern. We opted for a banal way of showing the incident, of narrating an accident like that. Usually, they show a family, that family lives in a house, and then you know that something terrible’s going to happen to them.”

“But we put the camera under the car in order to show that it could be anyone’s car. Yours. Mine. It’s down to mechanics you don’t understand. Only bits and pieces of metal are under the car. You get into the car, start the engine, you move off. Somewhere located deep down underneath the car is death. I absolutely clearly wanted to make it understood that in the film it’s fate.”

There’s a sense in which, travelling by car necessitates that one doesn’t think about that possibility, otherwise one would never travel. “Yes, if you imagine life like that, you’d never be able to go out the door. Sometimes, you have to think about things like that, that this fiction surrounds us everywhere.”

Perhaps, for most of us, the time we’d think about such things would be after we had survived a car crash. “Yes. When you’ve seen an accident on the side of the road, you tend to drive a little slower. Certainly for the next week or so – then you come back to your own speed. Then you see another accident, and for the next week or so you think about such things. These thoughts come to us.”

The unsettling fact of the husband’s telling a joke prior to the crash, as one does when driving along. Then, when fatally injured, he repeats over and over the joke’s punchline. “I think that it says something about the character of the husband. He repeats the same punchline twice. I didn’t really have any opportunity or chance to say any more about him, nor did we want to. We wanted to say a bit about his music and a bit about how he wrote…”

Strange, because if one is watching a film about someone who’s bereaved, it seems inevitable that the person of whom the character’s been bereaved creeps into the film almost by their absence.

Danusia Stok (interpreter): You feel their presence through their absence?

“That’s how we tried to do it, yes. We thought it much more interesting to do it this way than to do it visiting a cemetery or looking at photographs. That his presence would be shown in a different way through somebody else and within somebody else with regard to his physical presence.”

Part of the challenge of making the film must have been to find visual equivalents for that. (Certain sound ideas already exist here, since the bereaved is a musician.) I’m thinking of the swimming pool sequences, for example, where she hears his music. In terms of the visual elements too, the swimming pool itself or the musician that one sees playing on the street.

(I flip the cassette tape.)

Do you find in the process of putting the film together that finding those visual means to something not inherently visual excites him creatively. “Yes, I do like to find visual equivalents like that. Making films is such a boring process that it helps alleviate it to look an interesting solution (or lots of them).”

I confess to being an admirer of his Blind Chance. “An old film.” . But nevertheless interesting in terms of its triple parallel time structure. “One of the things is trying to make the boring profession of filming more interest in experimenting. How to learn to fulfil the conditional tense. There, it was very straightforward. But how to do this in film – that’s something I tried in Blind Chance. The conditional imperfect: if at a certain moment, he had been in such a situation, then things would have been different. Had things been different, then this would have happened.”

Do you find that the language of film still excites you, even all these years later? “Whenever I play, of course, I’m constantly making notes for my experiments. I do try more and more to find literary solutions to films in the sense of “concerning literature”. I rate literature much more highly than I do films. It’s incomparably more flexible. Sometimes in films I tried to find solutions which in literature are quite straightforward. Not necessarily in terms of grammar.”

That begs the question, why doesn’t he write a book? And, sure enough, there’s Kieslowski on Kieslowski coming, which turns out to be written by this interview’s interpreter, Danusia Stok.

ENDS