Director – John Woo –1992 – Hong Kong – Cert. 18 – 128m

*****

One of the greatest action pictures ever made – back in a 4K Restoration for the Opening Gala screening of LEAFF10 (London East Asia Film Festival 2025) on Thursday, October 23rd 2025

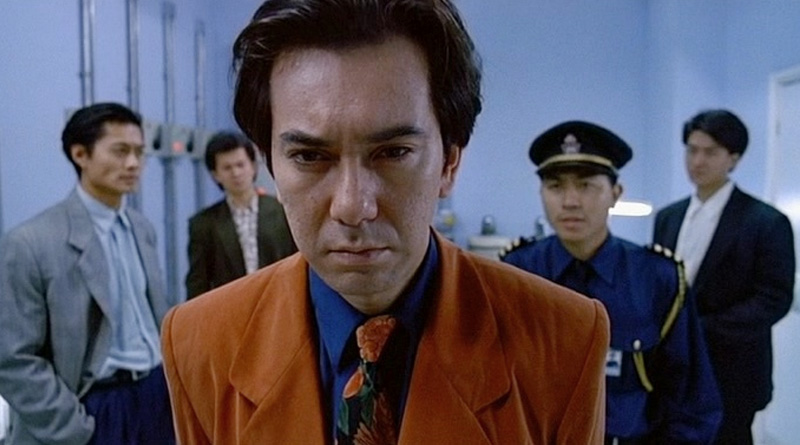

Woo’s directorial valediction to Hong Kong, at least for a time as he attempted to break Hollywood, rehashes his now familiar territory of brotherhood, loyalty and betrayal, etched in trademark bullets and blood with grander and greater operatic flourish than his earlier efforts. On-screen alter-ego Chow Yun-fat (The Killer, John Woo, 1989; An Autumn‘s Tale, Mabel Cheung, 1987) is cast for the first time in Woo not as gangster but cop, bonding with a ruthless triad hit man Alan (Tony Leung Chiu-wai from Bullet In The Head, John Woo, 1990, In The Mood For Love, Wong Kar-wai, 2000; Lust Caution, Ang Lee, 2007; Shang-Chi And The Legend Of The Ten Rings, Destin Daniel Cretton, 2021). For good measure, Woo throws in therising, young gangster killing the old leader to take over the mob from A Better Tomorrow (John Woo, 1986) (here played by Anthony Wong and Kwan Hui-sang respectively).

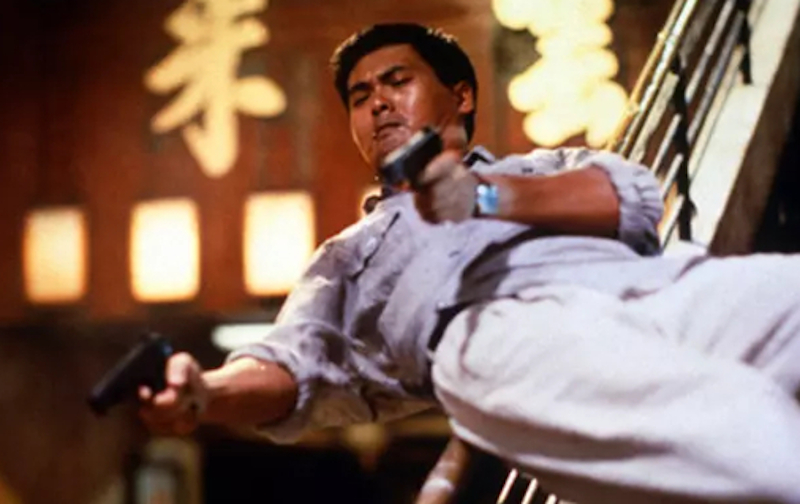

Hard Boiled opens with a spectacular tea house shoot out where Insp. ‘Tequila’ Yuen (Chow) accidentally shoots his partner (just as Leung, who turns out to be an undercover cop, mistakenly shoots a fellow officer during the later hospital shoot out).

Other memorable set pieces include the new gangster faction battling the old in a warehouse before being surprised by Chow’s swinging in from the roof and the film’s entire second half, wherein a police raid on a hidden underground arms cache turns the hospital above into one of the cinema’s bloodiest and most pyrotechnics-ridden battle zones.

Less grandiose hits, fights and even the intermittent romantic interest (Chow’s code‑cracking cop girlfriend Teresa Mo from Mama’s Affair, Kearen Pang, 2022; Over My Dead Body, Ho Cheuk Tin, 2022) are equally impressive, however much they appear not to be the main reason for making the film.

If Woo makes less of Chow / Leung’s guilt from the accidental shootings and treats the cop/assassin bonding much more cursorily than in The Killer, he explores other avenues. Chow’s acting range is allowed to run the full gamut, from light comedy through romance and ballistic stuntwork / gunplay to the finale’s intensely dramatic tragedy. Leung, meanwhile, makes paper cranes for each person he kills – and heartbreakingly must shoot the old boss and his men to gain the respect of the new, managing a brief smile in the process.

Wandering in through warehouse gunsmoke, Chow’s and Leung’s guns suddenly come cathartically face to face, just as later do those of Leung and Wong’s eyepatch‑wearing, right-hand man Mad Dog (Phillip Kwok, also the film’s stunt arranger) across terrified patients in a hospital waiting room.

On each occasion, both men put down their guns – in the former because they’re on the same side, in the latter because although each wants the other dead – both want the innocent bystanders to leave without getting hurt (in the event, many of the bystanders are promptly shot by the arriving ‘immoral’ Wong).

Woo himself turns up as a barman mentor to the clarinet‑playing Chow in a small jazz dive. The film benefits greatly from a tense and memorable score by jazz musician Mike Gibbs.

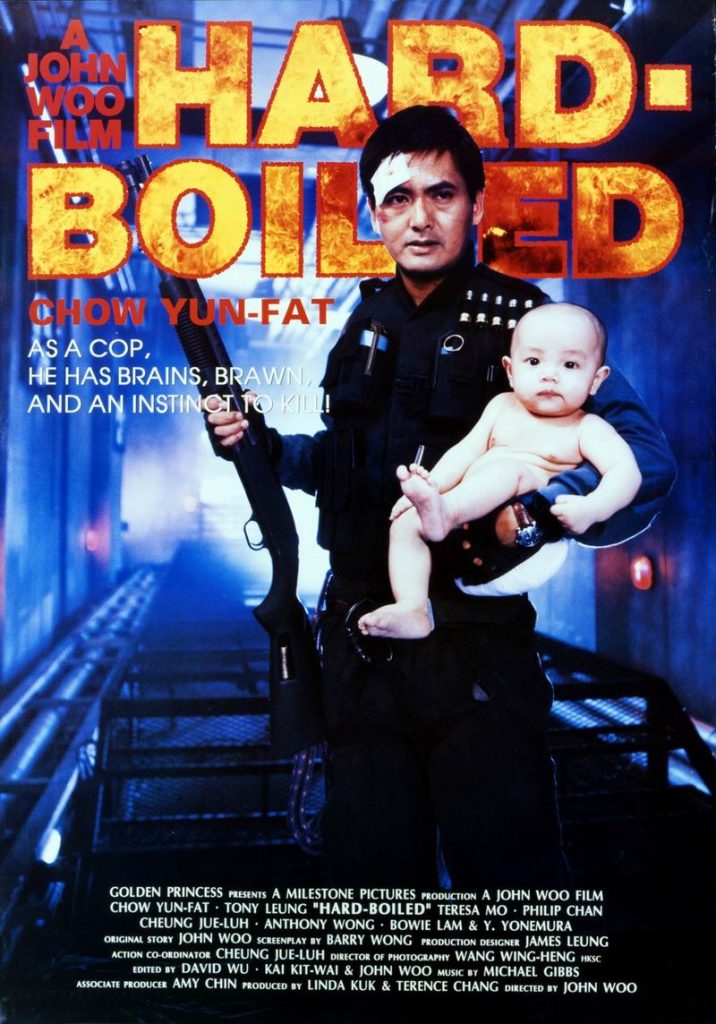

Elsewhere, in a thread unimaginable in Hollywood at least before Woo, the stakes are upped when Teresa Mo has to evacuate a full ward of babies before the hospital explodes.

Woo subsequently augments one of the contemporary cinema’s classic action images, as Chow leaps from an explosion behind him with a babe in arms. (The publicity shot for the poster showed Chow holding a shotgun in one hand and a baby in the other).

Such images suggest not brotherhood and male bonding but fatherhood and family…a seam Woo would subsequently mine further in his third American film Face/Off (John Woo, 1997) as he began to get to grips with the American milieu.

Hard Boiled is dedicated to scriptwriter Barry Wong (City Cops, 1990) who died in 1991.

Back in a 4K Restoration for the opening Gala screening of LEAFF10 (London East Asia Film Festival 2025) on Thursday, October 23rd 2025.

LEAFF10 runs from Thursday, October 23rd to Sunday, November 2nd.

Original UK Cinema release 1993.

Trailer: