Director – Ryan J. Sloan – 2024 – US – Cert. 15 – 114m

***

A single-parent mum, unable to make sense of the passing of time, struggles to get by and find the money to get out of town with her child – largely incomprehensible yet strangely compelling, urban, neo-noir thriller is out in UK cinemas on Friday, July 25th

This narrative impresses and frustrates the viewer in pretty much equal measure. There are rotten films out there on which you really don’t want to waste your time, and for all its faults, Gazer isn’t one of those (although there are times, particularly in its first hour, when it comes close). And then there are (arguably) visionary films where you can sense the makers – usually the director(s), writer(s) or performer(s) – struggling to express (a) unique viewpoint(s), and Gazer, a first-time feature by former New York electrician Sloan, who co-wrote and directs, and Canadian musician / actress Ariella Mastroianni, who co-wrote and stars, most definitely fits into that category – albeit not always entirely successfully.

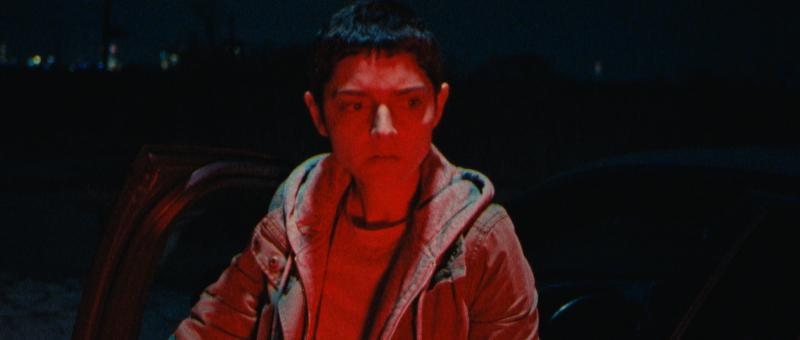

The film possesses a distinctive look, which I imagine is largely down to Brazilian-Portuguese cameraperson Matheus Bastos, who shot it on 16mm. Sloan co-edited it as well, but it feels way too long and would probably have benefited greatly from a fresh pair (or pairs) of hands coming at the material and fashioning it into something more coherent in the editing room. And yet, there is something here struggling to express itself, and in places the film is both arresting and compelling. It’s clearly been made on a shoestring budget with a great deal of love and commitment from all concerned, and makes you want to see what either Sloan, Mastroianni and / or Bastos – either together or separately – will do next.

Location-wise, although the film appears (as far as I can tell, with scant help from the hopelessly basic production notes) to have been shot in unfamiliar, lower rent parts of New York City, what comes over is an urban environment that could be anywhere in the Northern, less than sunny part of the US or the Southern, less wintry parts of Canada. Like so much in this film, this is a two-edged sword.

On the plus side, the settings have an almost Kafkaesque feeling to them, they could be an urban anywhere, further anonymised by Bastos’ rough around the edges, shoot it and get it in the can without worrying too much about making it look good approach which at once serves the piece well by making sure everything gets shot. On the minus side, this approach simultaneously undercuts the vistas by making them not look especially compelling to the eye.

These positive and negative aspects are compounded by large chunks of the film being shot at night rather than in daylight (although considerable amounts of the narrative take place in interiors with few windows and lit by artificial light). Moreover, in overall feeling, the piece seems to fall somewhere between a Canadian film and a New York film, as if unsure of its geographical and cultural identity. Lots of movies have been shot in Canada (and elsewhere) doubling for New York over the years, which scarcely helps.

The script potentially sets itself up to fail from the get-go with the conceit that widowed single mum protagonist Frankie (Mastroianni) struggling to financially get on precarious hand-to-mouth jobs by so she can amass the funds to get out of town with her child, suffers from dyschronometria, which means she struggles to make sense of the passing of time. Now, if you’re going to tackle a subject like this on the screen, you’d better have some effective strategies for making it work so that the audience can follow what’s going on. I’m not saying you have to spoon feed the audience, that you can make them work – look no further than, say, Kieslowski’s Three Colours trilogy (not his debut works) to see this done brilliantly – but I am saying that you need to present the puzzle pieces – or at least enough of them – on screen or soundtrack in order that the film can make narrative sense, which this one often doesn’t.

Another touchstone is Memento (Christopher Nolan, 2000, not his debut film) in which the protagonist suffers from memory loss and employs various coping strategies to help him (and the audience) keep track of what’s going on. In Dazer, Frankie plays what appear to be self-help audio-cassette tapes on her Walkman as a means of getting through the moments, minutes, hours and days; unlike Memento’s coping strategies, these aren’t much help to the audience in trying to work out precisely where – or more accurately when – we are at any given moment in relation to all the other moments in the film. Some sort of timeline or map or overall plan is required to help us make sense of the narrative, but sadly, in the hands of these particular, inexperienced filmmakers, that very necessary guide either isn’t here, or hasn’t been developed enough to the point where we can see it and make use of it in terms of the experience of watching Gazer.

And yet, lurking or swimming within this cinematic fog or soup, elements of the environment and the characters prove surprisingly and unexpectedly compelling. That’s particularly true of co-writer Mastroianni’s near-ubiquitous presence as Frankie, the performance which carries the piece. She fits a certain, familiar, visual female type (short, dark, cropped hair; vulnerable, lacking in confidence) yet projects something about an insecure person struggling to take control of her life.

It doesn’t really work out for Frankie, though. At the start, she is listening to the cassette voice telling her: “Focus. What do you see?”, but her concentration on that admonition, and an upstairs window where one person is (or maybe) assaulting another, causes her to not carry out her job as a petrol pump attendant (in the face of an admittedly, particularly unpleasant customer) and lose her current job. If she’s focusing, it may be on the wrong thing. Where her head is at is not especially helpful in terms of surviving everyday life, and since the film attempts to put itself in her immediate head space, that is not particularly helpful to the filmgoer.

In the end, even if it’s a deeply flawed, inexperienced beginners’ effort, Gazer is genuinely possessed of vision and, as such, well worth seeing. At the same time, in terms of comprehensibility, it’s a less than satisfactory viewing experience, and you may find yourself struggling to make sense of parts of it. Just don’t say you weren’t warned.

Gazer is out in cinemas in the UK on Friday, July 25th.

Trailer: