Director – David Bickerstaff – 2024 – UK – Cert. U – 93m

****

Late nineteenth century society portrait painter John Singer Sargent was fascinated more by their clothing and the possibilities of paint than he was by the women he painted – documentary is out in UK cinemas for selected screenings from Tuesday, April 16th

Based on the exhibition first at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA) and now at Tate Britain, this opens with incidental music that conjures a contemporary dance floor, a soundtrack which provokes a strange tension with paintings hanging on walls and costumes displayed in glass cases as the camera moves through the physical spaces in which they are displayed. But then, the title suggests this might be a little different from Exhibition on Screen’s usual fare.

John Singer Sargent’s A Portrait of Miss Elsie Palmer (A Lady In White), 1889-90, shows the energy and intensity of his portraiture. The brushstrokes are arresting and like nothing else being done at the time. The paintings might be perfect, but the people within them most definitely are not: Sargent captures their imperfections in a most compelling way. He looked deeply at people, and some of his sitters were afraid to sit for him because of what he might see. He had an exuberant feeling for life – and paint itself.

Portrait of Lady Sassoon (Aline de Rothschild), 1907, is displayed alongside the opera cloak that she wore for that portrait.

MFA’s Erica E. Hirschler notes that these are paintings where the clothing used actually survives. You can see what he changes (of the garment) to make a picture.

John Singer Sargent was born in Florence. The family kept returning there. His mother loved travelling, and got him (and his sister Emily) drawing the great European cities. He was sent to Paris to study art under the unconventional Carolus-Duran who pointed him at Franz Hals and then Velázquez. Sargent was great friends with Monet, painting him en plain air.

In 1879, aged 23, he went to Madrid to see Velázquez’ paintings for himself before going further South to Grenada to discover Spanish music and the flamenco tradition associated with Roma people. El Jaleo, 1882, is based on sketches of guitar players, dancers. This obsession with dark space recurs in The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, 1882.

His process painting a sitter is shown by a sequence lap-dissolving four black and white photos of the artist at work.

Massachusetts professor Paul Fisher talks about Sargent’s love of the exotic. This theatricality came to the fore with the dancer Carmencita, of whom footage in full motion was shot (and briefly shown here) by cinematographic pioneer Thomas Edison in 1894. Yet Sargent’s La Carmencita (Carmen Dauset Moreno), 1890, paints he fixed in a static pose, as if paused and still, although the picture is full of motion and movement in the way Sargent’s brushstrokes capture the details of her costume.

Sargent was fascinated by bold, edgy, stagy women, although he himself was quite a shy man. Note the theatricality of his portrait of the actress Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth, 1889, wearing a beetle wing dress designed for the 1888 production by Alice Comyns Carr. Sargent stages the character with the crown above her head, an invention on his part since it never appeared in the production at the Lyceum, yet it seems to condense the play’s theme of a lust for power into a single image.

Fowle talks in some detail about Sargent’s portrait of Mrs. Charles Thursby (Alice Brisbane), c. 1897-98, an American who had married into English money but who was also a great supporter of women’s suffrage. Rather than let her wear the fashionable dress she had intended, her paints her in more down to earth, everyday clothes in a pose where she looks ready to rise up and spring into action. She is subtly dressed in the colours green, white, and violet or GWV – Give Women the Vote.

Mark C. O’Flaherty, writer and photographer, talks about the process of dialogue in shooting a person as a subject. He wants the person – or client – to feel like they are representing themselves. If they are already performers, they may have their own mode that they’re comfortable with that you can’t really change (he has photographed both Siouxsie Sioux and Lisa Stansfield). He is particularly impressed by Sargent’s black on black pictures such as W. Graham Robertson, 1894, patron of William Blake and part of the queer circle around Oscar Wilde. With its hand on hip pose and a poodle with a yellow ribbon, the whole thing is incredibly camp. “When I look at Sargent’s work, I see the work of a queer artist,” says O’Flaherty.

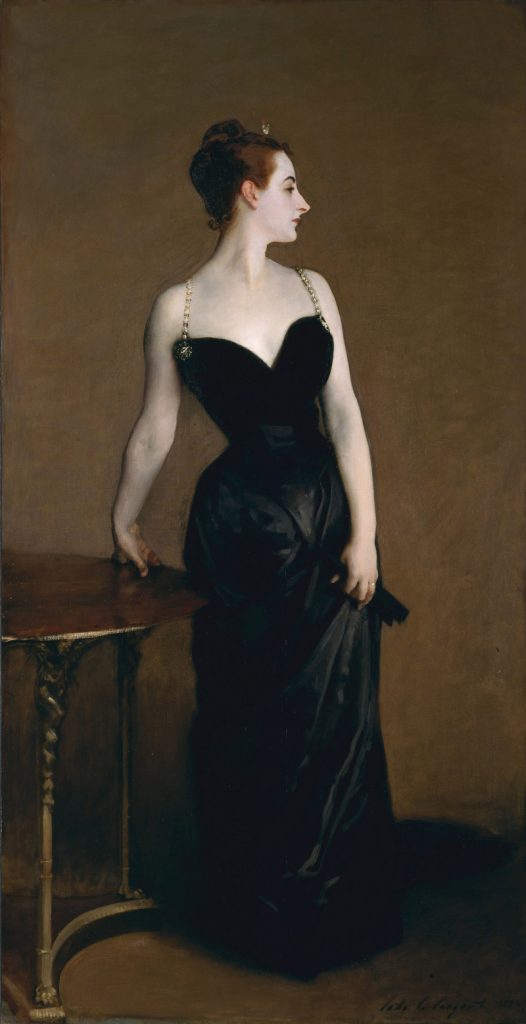

Madame X – Madame Pierre Gautreau (Virginie Amélie Avegno), 1883-4, is the famous Sargent painting of a woman in black, who at 19 married a French banker twice her age and became a socialite and the subject of newspaper columns. Sargent became fascinated by her beauty and desired to paint her. Her body faces us; her head is in profile. It’s full of torsion and twist, says Fowle, and a kind of energy. You can see the muscles in her neck feeling the tension of her pose. The artist complained she was difficult to paint, but Fowle thinks this was part of the subject’s social performance that the artist was quite interested in. According to Hirschler, he originally painted one of the dress straps off her shoulder, as if the dress could drop in seconds revealing her to be nude. When it was finished, she called it a masterpiece.

However, Paris was shocked to see one of the elite portrayed in such a sexually provocative way. The lavender pallor of her skin and her deathly appearance also had an impact; it was not received well, and the lady and her mother begged Sargent to remove it from the show, but he refused. After all, says Hirschler, it was a collaboration between both artist and subject.

After its run in that year’s Salon, he repainted the dress strap that was off her shoulder so that it was now on her shoulder Just after Gautreau died in 1915, he sold the painting to the Boston.

Following the Gautreau debacle, he was persuaded by Henry James and others to move to London. He moved into Chelsea, hiring Whistler’s former studio in Tite Street, and lived just down the street from Oscar Wilde.

His one London success was Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, 1886, in which two young girls hold Chinese lanterns as the sun sets. He painted en plein air for 20 minutes nightly, abandoning it over the winter, to observe just the right effect of the light. It took him two seasons and was to prove a great success. But his progressive French style was too much for Britain, and he fared better when he moved to America to paint the nouveau riche, who flocked to him for portraits. In 1900, he was awarded the contract to do the murals for the Boston Public Library and later for the Boston MFA.

He mostly abandoned portraiture around 1907, aside from a few friends or commissions he couldn’t get out of, in order to keep his creativity going, says Hirschler. He would take his extended family on hiking trips to the Alps, dressing them in costumes from a trunk when they stopped for a break. After 1900, he often worked in watercolour.

The twenty foot wide Gassed, 1919, (in the Imperial War Museum) shows a line of soldiers who had been attacked with and blinded by Mustard Gas.

Sargent died, unexpectedly, in Tite Street on the eve of a journey when he was due to take the last of his murals to America.

The documentary ends as it began – the music picks up a repetitive dance beat and rapid cutting juxtaposes Sargent’s images as we’re told how relevant an artist he is for today.

The material shot in Tate Britain housing the exhibition is periodically punctuated with camera moves around the exhibition itself, similarly emphasising spaces and voids around and between the paintings and fashion exhibits, with divisions of vertical panes of glass which you realise, after you’ve been watching the documentary a while, seem to somehow riff of the paintings themselves and the spaces Sargent places within them. In terms of specific exhibition layout and design, it was clearly an extraordinary use of the exhibition space, and the clever and highly appropriate use of the camera within that space captures it magnificently.

Moreover, there is some great interview material here: some of the academics get really fired up talking about various aspects of Sargent’s art, world and work processes, and their evident enthusiasm and passion for his work is infectious.

However, there is a glaring omission in all of this, an elephant in the room. Sargent came from a background well enough off to travel extensively and his career as a portrait painter served the rich elite of his day. His late works – the watercolours, the First World War painting – are mentioned as little more than a footnote – but perhaps he had had enough of servicing the elite. Western art is full of practitioners in the service of the Catholic Church and / or the monarchy, but the nineteenth and early twentieth century France in which Sargent worked saw many artists abandoning such patronage to pursue a singular vision (Courbet, Monet, Degas, Van Gogh, Gauguin), sometimes doing so in poverty.

Like Sargent, at least as presented and discussed here, this documentary simply embraces his elite clientele without asking questions about it. Is it okay to represent people simply because they are social elites – or does that give us an art that’s out of touch with ordinary people? This is not an accusation you would level at Van Gogh. However, listening to the various people interviewed, and looking at these images, this question never even comes up.

Instead, the unquestioning embrace of this aesthetic is underscored by interviews with present day photographers working with contemporary celebrities like Kate Moss, the Monty Python team or Helena Bonham Carter. It may be that Exhibition on Screen’s format of art and the art world, which in previous productions has served them well, has let them down here by omitting to place the section of society Sargent serviced in his portraiture within a wider social context and raise the questions that that begs.

Exhibition On Screen: John Singer Sargent: Fashion & Swagger is out in cinemas in the UK for selected screenings from Tuesday, April 16th.

Trailer: