Directors – David Bickerstaff, Phil Grabsky – 2025 – UK – Cert. 12a – 101m

***

A look at the turbulent life of sixteenth century Italian painter Caravaggio, his troubles, his forced travels, and his art – out in UK cinemas from Tuesday, November 11th

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571–1610), generally known as Caravaggio, is here, initially, curiously and somewhat confusingly referred to as Michelangelo only to be called Caravaggio throughout the remainder. The narrative of the artist’s life is built around talking head footage of actor Jack Bannell as Caravaggio himself speaking his own words – except that, they aren’t his own words since, as is pointed out later, this particular artist wrote very little himself and most of what is known about him today comes from police records of the time.

The framing device with the actor is supposed to be Caravaggio recalling his life on the boat trip back to Rome. Historically, he mysteriously disappeared after landing and was never seen again. Alas this latter fact – which might have made a great framing device – is only clarified at the end, at which point it plays merely as a less than satisfying conclusion.

Also included are a handful of art experts – historian Helen Langdon, artist Stephen Nelson, Caravaggio author Fabio Scalatti and Letizia Treves, Global Head of Research and Expertise, Christie’s – all of whom have a great deal to say about the various works of the artist which appear here. This is a regular feature of the Exhibition on Screen series, the people concerned are well chosen, and the production team carry off these experts’ involvement effortlessly.

Caravaggio was born in Milan in 1571, at that time beset by plague, famine and warfare. After his father – a sculptor who was also deeply religious, i.e. Catholic – and his grandfather died of the plague on the same day, he was raised by his mother. As soon as he could, he headed to Rome where, according to Treves, he survived on artistic hack work – executing copies of devotional works in exchange for bed and board, painting three heads a day or doing half-length figures. Eventually he secured a position in a minor artist’s workshop.

He tended to use a small circle of close friends as models – Mario Maniti can be identified in such works as Beautiful Bacchus (c.1596). The artist cast his lady friend Filide – described in Jack Bannell’s monologue as someone who’d do anything for money – as St. Catherine (1598-9) and Judith Beheading Holofernes (c.1599).

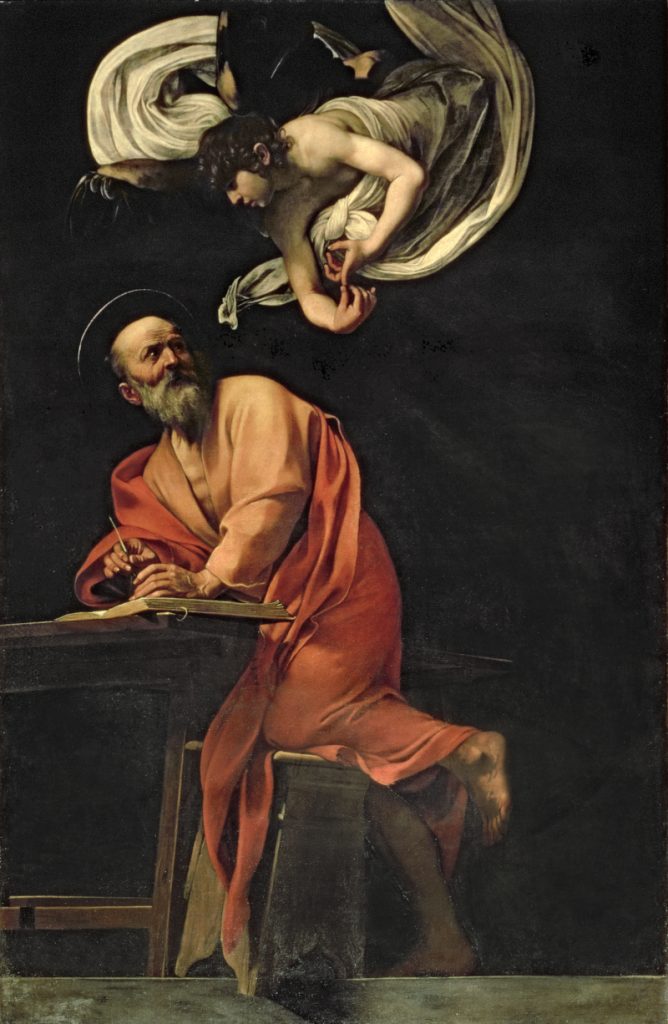

One of his first paintings to be displayed to the public was The Martyrdom of St. Matthew (1599-1600), which demonstrated a highly emotional response to the Biblical text. By the time of The Inspiration of St. Matthew (1602), he was using little tricks to draw the viewer into the painting such as one leg of a stool hanging off the edge of a solid floor at the bottom of the image. He similarly invades the viewer’s space in Christ at Emmaus (1601) with a plate of food protruding over the edge of the meal table on the side nearest to us.

As much at home in the streets as the studio, Caravaggio was as adept with the rapier blade as the paint brush, and when one of his numerous fights led to the death of an opponent, he was forced to flee Rome, where he had made something of a name for himself as a painter pushing the boundaries of art. He headed South, staying for a while in each of several Italian cities or districts – Naples, Malta, Valetta and Sicily – before having to move on for one reason or another. This journey gives the actor’s monologue and the overall film additional structure, allowing for much filming of both geographical locations and works of art in situ, both of which elements are Exhibition on Screen’s stock-in-trade, and something which, here as elsewhere, they do very well.

In Naples, he painted The Seven Works of Mercy (1606-7), described by artist Stephen Nelson as “the most problematic painting he ever did – and I think her knew it.” He carried on South, securing a portrait commission of Alof de Wignacourt and His Page (1607-8) in Malta, and creating The Beheading of John the Baptist (1607-8) in Valetta. In Sicily, he fell in with the Knights Templar for a while, until that situation, too, soured, producing such works as The Burial of St. Lucy (1608) – notable for its area of darkness above the figures – The Raising of Lazarus (1609) and The Adoration of the Shepherds (1609).

When he eventually undertook the return journey to Rome, he came back via Naples where he completed David and Goliath (1606-10) in which he painted his own severed head as that of Goliath.

Many of the Exhibition on Screen films are built around a recent, current or forthcoming art exhibition, providing an obvious peg on which to hang (and with which to sell) the production. This one has no such hook, falling back instead on the actor playing the artist and the travelogue aesthetic. The actor footage gets tiresome after a while: perhaps there is simply too much of it, or perhaps Caravaggio’s hot-tempered lifestyle, with all its fights and flights, cries out for more dramatic footage of the actor fighting or fleeing, something which would make a marked break from what Exhibition on Screen have done in previous films. The travelogue aspect is rather more successful, even if the artist’s mysterious disappearance before he reached Rome closes the film at an unsatisfactory dead-end.

Exhibition On Screen: is out in cinemas in the UK from on Tuesday, November 11th. Check your local cinema for details or click here.

Trailer: