Director – Kirsten Johnson – 2020 – US – 89m

*****

The director imagines the death of her dad in a film which celebrates both the man himself and the art of cinema – on Netflix worldwide from Friday, October 2nd

I was alerted to this movie both because not only was Johnson’s prior Cameraperson (2016) excellent but also the subject matter of this new film looked promising. Johnson spent three decades as the cameraperson on numerous documentaries (among them Farenheit 9/11, Michael Moore, 2004 and Citizenfour, Laura Poitras, 2014) before making her previous feature out of interesting bits and pieces of footage she had lying around. Her new film is highly personal and almost fits into the home movies or personal diary school of film making – lent an inevitable, additional gravitas given Johnson’s prior artistic and technical career.

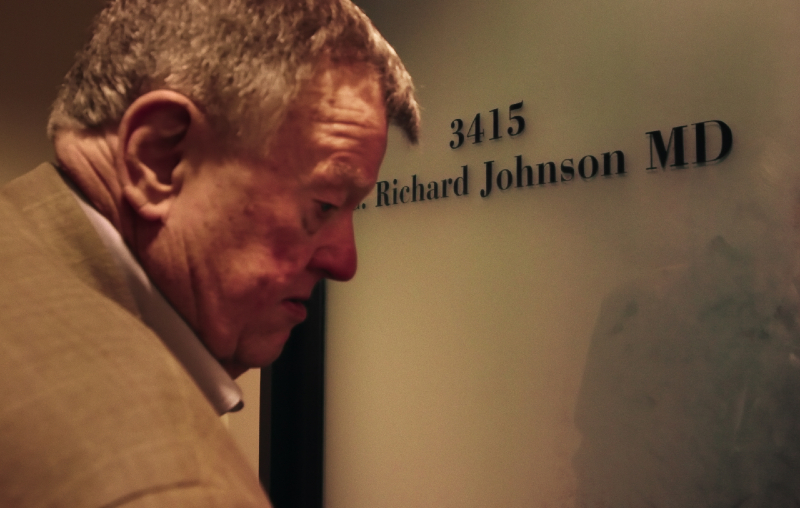

C. Richard Johnson (b. 1932 – ) is Kirsten Johnson’s dad. One day, like all of us, he is going to die. So his daughter decided that while he was still alive she would make a film about his dying, filming his possible deaths and staging his funeral service ahead of time.

There’s a huge contradiction at the heart of this idea. “Real life is often much more interesting than what you can make up”, Johnson says at one point, a statement I personally find compelling not because it’s an obvious raison d’être for documentary filmmaking but because it’s a justification found at one end of a particular filmmaking spectrum, the other end being, “you can make stuff up, create illusions, fantasy, screen magic” which is the model of cinema to which I’m primarily drawn.

Thus, in what is essentially a documentary, Johnson employs stuntmen, special effects make-up technicians and digital effects by unseen crew members to realise onscreen accidents, the occasional spurting of blood and assorted Heavenly scenarios. Her resultant film is consequently something of a genre-bender.

One sequence (previewed in the trailer) illustrates this perfectly. Dad is lying at the bottom of the stairs having tripped and fallen, one leg bent the wrong way at the knee (is he double-jointed?), a pool of blood beneath his head. “Can you just put one arm up against the wall?”, says his daughter offscreen. As he complies, the image shifts from scene of horrific, accidental death to ludicrous, staged artifice, the original illusion totally shattered. Oh Death, where is thy sting?

The film articulates its Seattle-born director’s religious upbringing in the Seventh Day Adventist church with its strict regime of “no alcohol, no dancing, no movies”. She was 11 when her clearly unorthodox dad took her to see Young Frankenstein (Mel Brooks, 1974). She was scandalised. He loved it.

That irreverence chimes with the joyous, religious aesthetic which infuses the stagings of Heaven here – dad and others hugging, chocolate to eat, pieces of popcorn flying through the air, all to a choir singing Gloria in Excelsis Deo. Elsewhere, Dick Johnson falls gracefully backwards into a pillow of clouds, landing on them as they support his weight.

You couldn’t make this film without the agreement and full co-operation of its subject… and Dick Johnson, a working psychiatrist prior to his retirement, is game. We first meet him in a barn near the family home in rural Seattle, which community is also the venue for an advance staging of his funeral while he’s still alive in 2016, for which he gets to try out his already purchased coffin.

As the film proceeds, it becomes clear that the subject actually isn’t death so much as loss. His all-too briefly seen wife Catherine Joy Johnson, Kirsten’s mum, died after a longer period of Alzheimer’s and following Dick’s relocation to New York to live near his daughter and grandkids we see him attend clinical memory tests. Later, heartbreakingly, we see the beginnings of the disease just starting to take hold.

Rather like her father’s pre-staged funeral, when a passed around microphone allows those present to share recollections and stories about the (not yet) deceased, Kirsten Johnson’s film is a compelling celebration of life, of an ordinary person, of goodness. Exploring good on the screen and making it as attractive as this is an incredibly hard feat to pull off. Embodying as it does the contradictions between representation, illusion, fantasy and memory, it’s equally, like Cameraperson before it, a celebration of the art of cinema.

Dick Johnson is Dead is on Netflix worldwide from Friday, October 2nd.

Trailer: