Director – Tim Mielants – 2025 – UK – Cert. 15 – 93m

****1/2

In 1996, the head, his staff and their students struggle to get through a particularly difficult day at a school for troubled teenage boys – out in UK cinemas on Friday, September 19th, and worldwide on Netflix on Friday, October 3rd

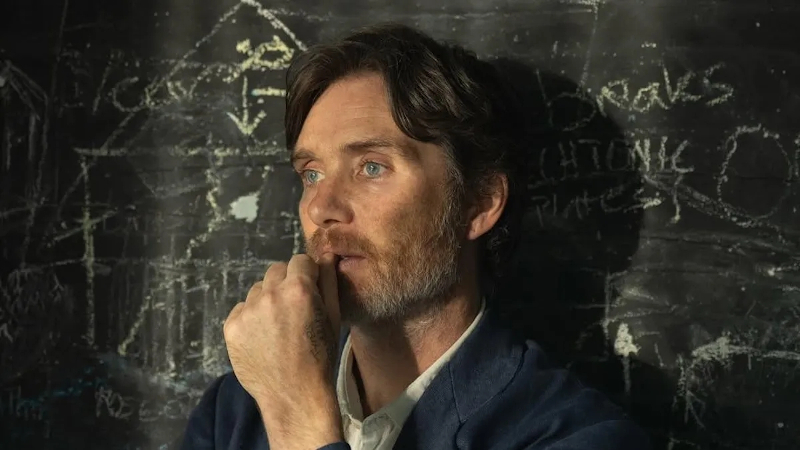

Steve (a burned out, visually unrecognisable Cillian Murphy, also the producer) is asked if he’s ready to do an interview to camera. He isn’t, but now is as good a time as any. He drives into work across a vast estate and spots teenager Shy (Jay Lycurgo) dancing to drum and bass music on his Walkman cassette player and smoking a spliff. Steve disciplines his pupil in a friendly manner, then returns to his car after being reminded that today is the day a TV film crew is coming to the school to film a segment for the local TV news magazine programme. Shy attempts, playfully, to ride on the bonnet of Steve’s car. Steve, talks him out of it.

Most of what follows, which covers the next 24 hours, takes place within the school buildings themselves, although the action occasionally wanders (or flies drone-shot style) out into and around the wider grounds of the school estate. If the title suggests the headmaster Steve as the main protagonist, certain parts of the proceedings indicate otherwise as the narrative at times, particularly later on, follows Shy (the protagonist of screenwriter Max Porter’s experimental, source novel Shy), and at others the school’s resident psychiatrist and counsellor Jenny (Emily Watson), various different students, the director and his film crew, and even a visiting MP (Roger Allam). Taking the school as made up of its staff, pupils and various visiting outsiders connected with it in one way or another, the protagonist is the school itself, or possibly the school as situated in its wider, tenuous location within society.

Historically, the day is clearly and very specifically located in the final year of the Tory administration that preceded Tony Blair’s 1997 landslide New Labour victory, a time when government cuts were the order of the day. Apart from the date, and the observation that the institution is on its knees thanks to years of government cutbacks and consequential, inadequate staffing levels, none of this is really mentioned, which ensures the film never becomes politically preachy. The cuts have clearly taken their toll, though, along with other elements in play – a visiting, well-fed, well-heeled (presumably Tory) MP, surrounded by yes-men and women, completely out of touch with ordinary people’s lives; the school’s visiting owners who deliver much worse news about the place’s future than the bad news Steve and his loyal and tireless staff are used to hearing from them; and an unscrupulous film director determined to take his crew beyond the boundaries of the restrictions on which his filming is conditional.

The 24 hours here telescoped into just over an hour and a half of cinematic time represents a perfect storm in the life of the institution. There are simply too many things going on at the same time, and if something CAN go wrong, it WILL. This may be the film’s great strength, the point where it transcends ideas about schools, education, government cuts, an out of touch political class, a self-serving, unregulated media, and so forth, to deliver a narrative about people having a very bad day. We’ve all been there.

There is something very English about it too: all those transcended factors play a part, but England has been having a very bad time for the best part of the last half century and like the Brexit vote, this film is an unfocused scream against the malaise afflicting our country without really knowing or understanding its causes or offering any idea as to how to constructively go forward.

The narrative is shot in chronological order, a method pioneered by British social realist innovator Ken Loach, as witnessed by lead actor Murphy on the set of The Wind That Shakes The Barley (2006). Director Mielants additionally deploys long takes which make great use of improvisation on the part of the cast. One uses the word improvisation hesitantly, because the whole feels grounded in a well-worked out script so that any improvisation feels like it is working on top of a well defined base. Early confrontations between boys in the corridor recall similar dynamics in Matthew Modine cycling and offenders vehicle Hard Miles (R.J. Daniel Hanna, 2003), yet this is very much its own film.

Steve’s long-suffering deputy Amanda is played convincingly by Tracy Ullman, and given a fair bit of screen time, while rapper Little Simz turns in a solid bit part as Shola, a young, idealistic teacher suffering what is coyly described by the film as inappropriate behaviour on the part of one of the students. Murphy, out of whose relationship with the writer the film grew and for whom the role of Steve was specifically written, is at the top of his game, while the far less experienced Jay Lycurgo as Shy proves at least Murphy’s equal onscreen. As in Small Things Like These (Tim Mielants, 2024), Watson delivers one of her strongest performances. Special mention should go to the eight or so youths playing the offenders, all of whom impress and who constitute a superb piece of ensemble casting. (I would love to credit them, but also the perfunctory cast list in the press handouts infuriatingly fails to list the lower echelons of the cast – and it isn’t like this is an epic with a cast of thousands, where such an omission might be thoroughly understandable.) Indeed, the whole movie is impeccably cast from top to bottom.

A 1996 white knuckle ride of a head teacher through a day in the life of the special school he runs, this is a deeply affecting film (especially, I suspect, for a contemporary English audience) which cries out to be seen. I don’t want to knock its being watched on Netflix, where in all probability most viewers will see it, but if you have the chance to watch this on a decent screen in a cinema, I would recommend doing so – with the proviso that there’s so much going on visually in the frame that you may enjoy this particular film more if you’re sitting some way back from the front, as I was. I had colleagues sitting near the screen who found the whole experience overwhelming, and not in a good way. Go out and see it, just don’t sit near the front.

Steve is out in cinemas in the UK on Friday, September 19th, and worldwide on Netflix on Friday, October 3rd.

Trailer: