Directors – Masashi Ando, Masayuki Miyaji – 2022 – Japan – Cert. 15 – 113m

**

The conquerors of a foreign land succumb to a mysterious plague there – out in cinemas on Wednesday, July 27th

This starts off with clearly epic intentions by throwing line after line of convoluted plot at the viewer in rapid fire, confusing intertitles. The kingdom of Aqifa was once ravaged by the Empire of Zol until the Black Wolf Fever prevented Zol from entering Fire Horse Territory. Today, the Black Wolf Fever is believed a thing of the past. Okay, got that? If not, you’ll be in trouble because the narrative is all about Zolians, Aquafaese and wolves and while the images are often ravishingly beautiful to look at, visually arresting eye candy in background or character design is never enough of itself to propel the story forward.

It continues piling on plot information like this for about half an hour. To make matters worse, an insistent cod-Gaelic score is overlaid over the images much of the time, and it seems composed to draw attention to itself rather than advance the story in any way.

Aquafaese toil in a salt mine (someone happens to mention some time afterwards that the mineral being mined is salt, otherwise you wouldn’t know) under sadistic guards while in the depths wolves attack and infest the slave workers whose skin comes out in purple blotches before they die. (An earlier image of the Black Wolf Fever consists of purple goop racing out of a forest.)

A doctor called Hohsalle, an Aquafaese working under Zolian occupation, is surprised by this since historically, for some unknown reason, Zolians have succumbed to the Black Wolf Fever while Aquafaese remained immune. The solution to this mystery (which is revealed towards the end) is one of the drivers of the film’s plot, and certainly forms the prime motivation of Hohsalle.

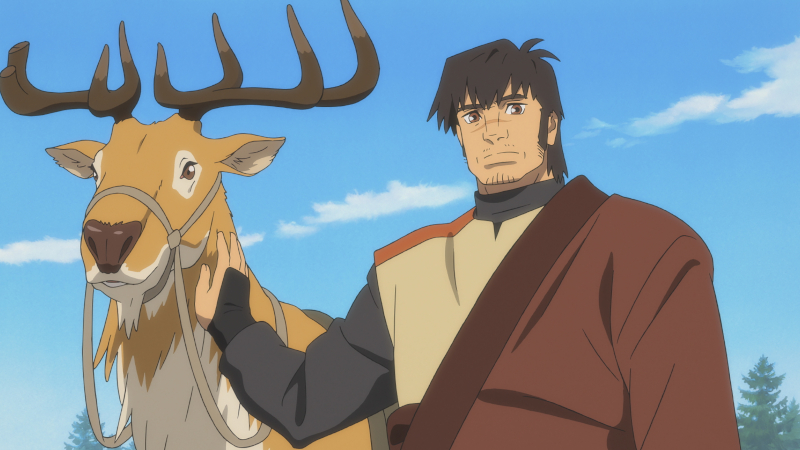

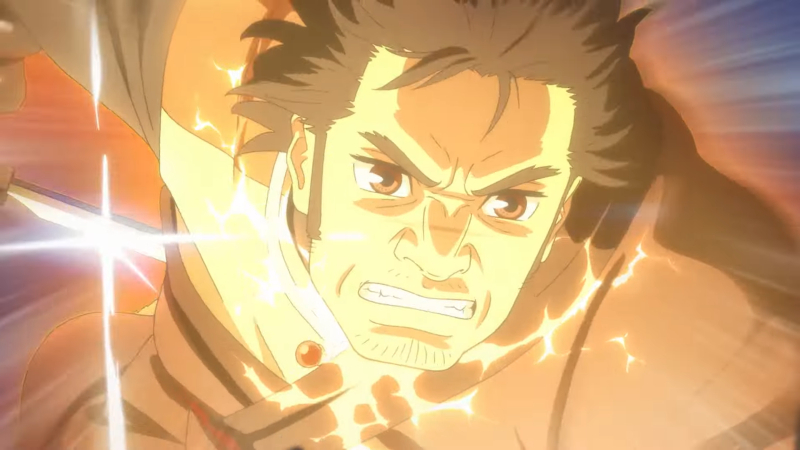

Also in the mine, a large Aquafaesan named Van defies a guard to carry the backpack of a collapsed worker. Later he gets bitten by a wolf but instead of succumbing to the fever glows intermittently from the bite marks on his arm whenever danger threatens. He adopts a small girl named Yuna whose parents have been killed by the plague, escaping the mine with her with the intention of reaching the Zol-free Fire Horse Village. (The full title translates as The Deer King: Yuna and the Promised Journey.)

On their trail is Hohsalle, who believes Van’s blood holds the key to combatting the plague, accompanied by his squire whose red cross tunic suggests he’s wandered in from medieval crusades as well as a skilled woman tracker.

After about half an hour, if you haven’t already lost interest, the directors manage to slow down their throwing of exposition at the saturated audience and the film intermittently improves, such as in the sequence where hapless small daughter Yuna puts herself in the path of a large charging hog under the wildly mistaken delusion that she can tame it like her father Van tames deer-like animals for riding.

These animals are called Pyuika, although given the film’s title and the fact that one of these animals attains a certain significance towards the end, we might all have been better off had the subtitles referred to these animals as deer. Whoever used recognisable rather than made up words to translate the title into English as The Deer King not The Pyuika King must have been aware of the problem.

The whole attempts to create a mythology not dissimilar to Princess Mononoke, (Hayao Miyazaki, 1997) with a disease resembling some of that film’s supernatural monsters, wolves and a medieval period aesthetic, throwing in mining, waterwheels and medical syringes for good measure. Alas, it lacks Miyazaki’s clarity at storytelling and doesn’t know how to structure itself so that the audience understands what’s going on, constantly confusing the audience by throwing in additional ideas or characters.

Unlike Mononoke, it doesn’t feel like a supernatural tale set in a Japanese feudal past so much as an ill-thought out past possibly in a quasi-European setting. There’s a Zolian emperor who has eyes everywhere in the form of dirigibles which can rise up from the ground at a moment’s notice, a bit like the Eye of Sauron in The Lord Of The Rings, except that Sauron only ever has the one eye in a fixed location, and its reach was far greater. The Zolian eyes are a great idea, but as with much else in this film, they’re never properly worked out and just adorn the plot as unnecessary decoration.

Both of The Deer King’s directors have considerable visual experience in the anime world. Ando was the animation director on such esteemed Ghibli fare as Princess Mononoke, Spirited Away (Hayao Miyazaki, 2001) and When Marnie Was There (Hiromasa Yonebayashi, 2014). Not to mention on other, non-Ghibli productions including Your Name, Weathering With You (Makoto Shinkai, 2016 and 2019), Tokyo Godfathers and Paprika (Satoshi Kon, 2003 and 2006). Miyaji, meanwhile, was storyboard artist on Japanese animated TV series Sword Art Online (2012) and Attack on Titan (2013-present).

The current film, however, is a salutary reminder that excellence in one area of filmmaking craft is not of itself enough to guarantee the ability to direct a coherent narrative feature. Lots of directors attain the position via this route, not only in animation but also in live action, and sometimes it works out. Not so here. The duo’s pedigree, particularly Ando’s with his Ghibli history, make the film an easy sell. What that doesn’t tell you is just how much of a slog it is to actually watch. (The UK trailer, below, does a pretty impressive job of making sense of the incoherent plot. The feature doesn’t seem to make anything like as much sense as this trailer implies. You have been warned.)

The Deer King is out in cinemas in the UK on Wednesday, July 27th.

Trailer: