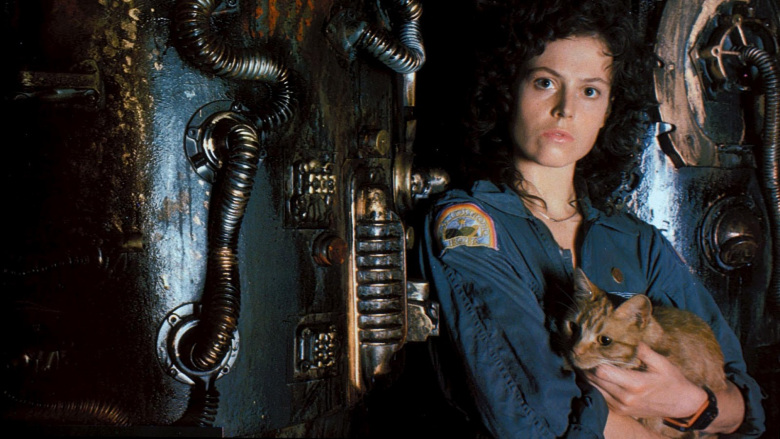

Alien

Director – Ridley Scott – 1979 – US – X – 116 mins 35 secs

*****

Blade Runner

Director – Ridley Scott – 1982 – US – AA – 117 mins 04 secs

*****

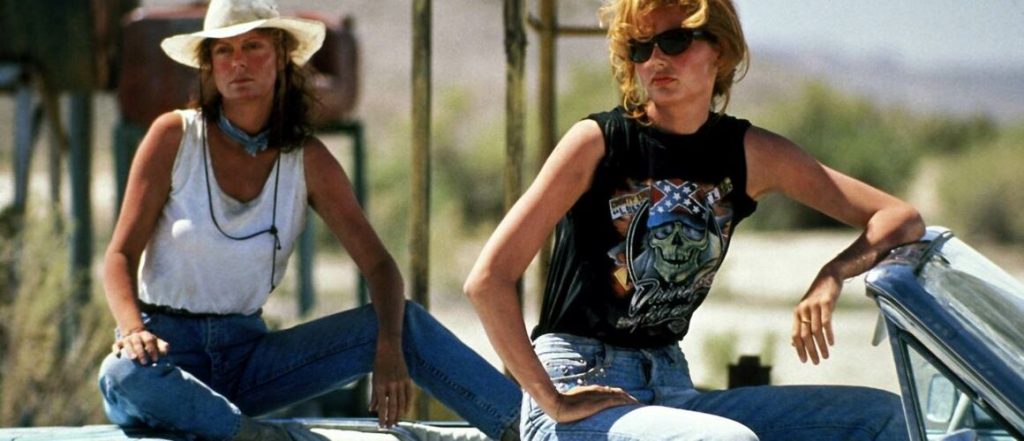

Thelma & Louise

Director – Ridley Scott – 1991 – US – 15 – 129 mins 22 secs

*****

At the end of Alien, Ripley (Sigourney Weaver), having defeated the monster, strips down to her underwear only to discover that she hasn’t defeated it at all and it’s still in the space shuttle with her in the archetypal Hollywood false ending of recent years. It begged the question, why did Ripley remove her clothing at this point if not for the obvious gratification of the male members of the audience (and, one should add, the accompanying box office returns)?

At the end of Thelma & Louise, the eponymous heroines (Geena Davis and Susan Sarandon respectively), on the run after the former’s rapist has been murdered after the event by the latter, find themselves trapped between the Grand Canyon’s gaping precipice on one side of them and massed hordes of police marksmen, ready to open fire if they don’t surrender, on the other. No pandering to male voyeurism here.

The linking element in both films is their director, Ridley Scott. After the immense box office success of Alien, Scott became typecast. First he was the science fiction/fantasy with special effects to go director of Blade Runner (1982) and Legend (1985); then, as these failed to net the audience interest necessary to justify their budgets, the Hollywood machine shifted him to cop thrillers, following Someone To Watch Over Me (1987) with Black Rain (1989).

Alien had actually been preceded by a period film called The Duellists (1977), after the Joseph Conrad story, which began as a French television project and ended up as the critically acclaimed full-blown feature film which won the Special Jury Prize at Cannes (and, incidentally, an entry in the BBC’s current Moviedrome season). That the film’s producer was David Puttnam points to Scott’s advertising origins – prior to forming a highly successful commercials film production company, Scott had worked for a New York design consultancy after studying at the Royal College of Art.

Film buffs file Scott under C for Commercials along with brother Tony Scott (Top Gun, 1986) and contemporaries including Alan Parker (Midnight Express, 1978), Hugh Hudson (Chariots Of Fire, 1981) and Adrian Lyne (Fatal Attraction, 1987). The critics have been quick to damn much of his work as that of the designer eye that visualises each frame as seductively beautiful. All very well, they argue, if you’re making a 30 or 60 second TV ad: not so good, though, if you’ve got two hours of movie in which to delineate characters and tell their story.

This alluring quality of the image is the very element that makes Sigourney Weaver’s stripping off so compelling. Scott’s best known ad may well be the Hovis commercial in which a boy with a bicycle climbs a sharply inclined street stylized as if somewhere in the Industrial North while a homely brass band plays on the soundtrack. He’s very good at creating these alluring visions too, even when regurgitating Blade Runner style in Apple Computer or Barclays Bank commercials of the early- to mid-eighties. But is this really enough in the case of astronaut Ripley? After all, there’s a malevolent otherworldly psycho-rapist out there who’s already brutally and fatally violated her crew mates one by one; maybe Ripley is peeling off the layers for his (I assume any such phallocentric abomination to be male) benefit as the monster’s next victim?

Scott’s follow-up to Alien, the futuristic Blade Runner, flopped. Despite the stunning visuals that had become his trademark, there were severe script problems. Audiences didn’t identify with the hero, a private detective played by Harrison Ford, but rather his adversary, a robot played by the the talented Dutch actor Rutger Hauer. The Christian mind has often commented on the replicant Hauer’s desire to be a man as other men, instead of company property marked for termination. Scott hammers this point home – in uncharacteristically bludgeoned style – by releasing that symbol of peace, a dove, from a rooftop at the climax of the fight between gumshoe and android. For me, the moody, rainy street backdrop of an overbuilt, unplanned metropolis with cheap sushi stalls at ground level and dirigibles floating through the overhead murk announcing “offworld entertainment” is much more memorable than the simplistic symbolism.

After Blade Runner, Scott’s movies seemed continually to not quite arrive at wherever they were supposed to be going. Legend nearly became a disaster of major proportions when one of Pinewood’s biggest stages caught fire during production. Although the visuals are magnificent, the film again flopped, probably because of its slight storyline. Scott’s visuals were taking over from his storytelling ability instead of working with them hand in hand. The “no light without darkness” philosophy ended up as little more than unicorns charging through ponds, a red Tim Curry with prosthetic horns and various midgets sporting similarly unconvincing effects make-up. The New York of Someone To Watch Over Me looked too stylish – the steam coming out of the pavements more closely resembled an expensive perfume commercial than a city full of menace. Black Rain‘s stunning images of Japan came closer to succeeding in terms of overall look and individual frame, but swamped the sketchy story of American biker cop Michael Douglas hunting a villain in Japan. It was the Blade Runner style reworked without the SF.

But in bringing Callie Khouri’s Thelma & Louise screenplay to the screen, Scott has surprised everyone (and reaped the box office rewards that had eluded him since Alien). Although the showy style of earlier films threatens to erupt on occasion – one point sees the camera track along the side of the heroines’ 1966 Thunderbird Convertible and another recalls Black Rain‘s bikers by parked vehicles in the foreground – it’s (mercifully) never given the opportunity. Furthermore, Thelma & Louise has both the very definite destination outlined earlier in addition to the piece’s impressive starting point.

The two women – the first a male-dominated housewife, the second a working waitress – set out on a weekend break by car but on the first night one of them gets raped. Rape in the movies is a subject too complex to dwell on here, but Scott shoots the scene unflinchingly in a car park in a manner that makes it very clear that, while Geena Davis may have been flirting, she’s now had a little too much to drink, is feeling sick and certainly isn’t asking for it when she and her dancing partner step outside the roadside ballroom for a breath of fresh air. It’s all a far cry from the viciously violated crew members, with accompanying striptease come on from the one woman who might just get out of the movie alive, at the heart of Alien.

Originally published in Strait – the Greenbelt newspaper, 1991.

Alien trailer (1979):

Alien trailer (Blu-ray/DVD):

Blade Runner trailer A (1982, voice over, 3m 27s):

Blade Runner trailer B (1982, music, 1m37s):

Thelma & Louise trailer (1991):